Harold at the Window

Published May 2019

By Nathan Gunter | 22 min read

Harold Stevenson long has been acknowledged as one of the greatest artists of the twentieth century, rubbing shoulders with Andy Warhol, Jackson Pollock, and other art-world luminaries. Now, the hometown he carried with him wherever he went—as well as his family, friends, and the art community—mourn the loss of one of their own.

On Idabel’s Central Avenue, in the building that once was the town’s movie theater, there is a law office on the second floor and a home health agency on the first. In the lobby—which few would walk through if they weren’t visiting one of those businesses—there’s a painting on the wall opposite an empty receptionist’s desk. In it, a heavy blue sky hangs over the movie theater in its heyday, the marquee glowing white against a rainy street that reads “Carnival in Costa Rica opening August 19.”

Details in the painting seem to glow: the neon of the theater’s sign, the lights of the box office, and the indiscernible movie posters shining through the rain. But a softer, warmer light emanates from the bottom left corner of the painting. It’s the artist’s signature: Harold Stevenson.

The painting dates from 1947, when the artist was on the verge of turning eighteen years old. The view of the theater is the one from the window of the studio Stevenson had opened in downtown Idabel at the age of ten. During his seventy-five-year career—which took him around the world to live and work alongside art-world greats like Andy Warhol, Peggy Guggenheim, and Jackson Pollock—Harold Stevenson painted what he saw, and what he saw was beauty.

It was the heart of the Great Depression when a ten-year-old Harold Stevenson opened his studio in downtown Idabel, where he’d invite residents in to sit for a portrait, for which he charged them a dollar. Despite the economic hard times, many locals took the young artist up on the offer.

One of Stevenson's early works is of the movie theater across the street from his childhood studio and currently hangs in the lobby area of a downtown Idabel office building. Photo by Megan Rossman

“Harold started painting in the 1930s during the Depression, and he painted that Depression as a child,” says Harold’s friend and biographer Dian Jordan. “As a ten-year-old child, he recognized it, understood it, and felt it, and he knew what it did to grown men who couldn’t find work and families that couldn’t feed themselves. Harold recognized all of those things, and that’s what he painted.”

Harold would paint anyone who came into the studio, be they black or white, rich or poor. He found each person he painted endlessly fascinating and worked hard to give them something to treasure.

“When he was a child, people would ask, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up, little boy?’ And he would say, ‘I am an artist,’” says Jordan. “He’d never say, ‘I want to be.’ He said, ‘I am.’”

At Idabel High School, Harold was president of the art club and the student council, art director of the school yearbook, and the winner of a national art contest sponsored by the Carnegie Institute. But soon, bigger things called. In 1947, he set out for Norman to study art at the University of Oklahoma. Though he befriended future Sooner State notables such as architect Bruce Goff, he found the college experience unfulfilling.

“He did not want to get a degree, because he was afraid he would be forced to teach art, and as long as you don’t get a degree, they can’t make you teach,” Jordan says. “He was not happy with formal art education.”

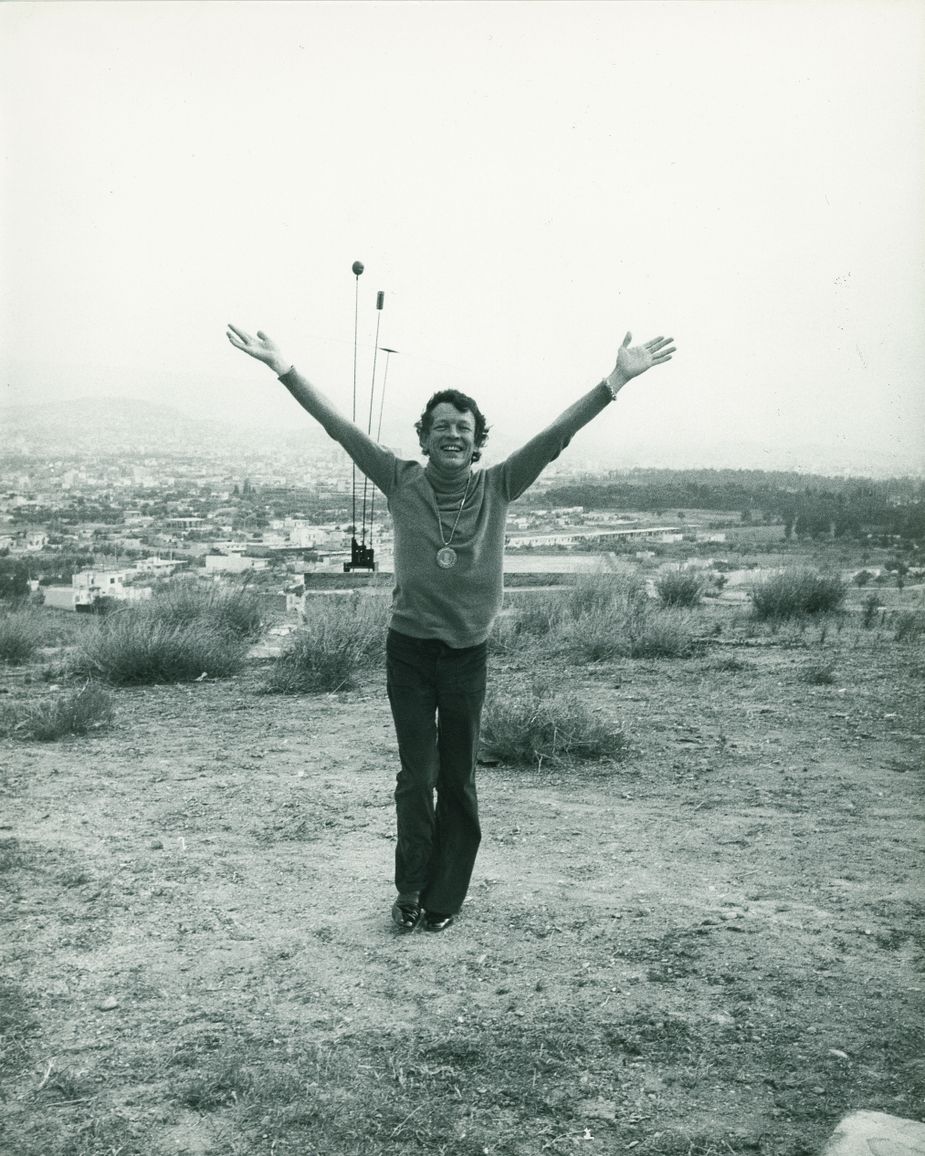

Stevenson stands in front of his friend Panagiotis "Takis" Vassilakis' sculpture in Greece. Photo courtesy of Clay Coldiron

So after two years, with seventy-five dollars in his pocket, Harold lit out for New York at Goff’s insistence, where he quickly made a splash. He got a gallery agent, Alexander Iolas, landed some choice exhibitions, and found enough high-profile buyers that he was able to help secure a debut exhibition for his new friend Andy Warhol.

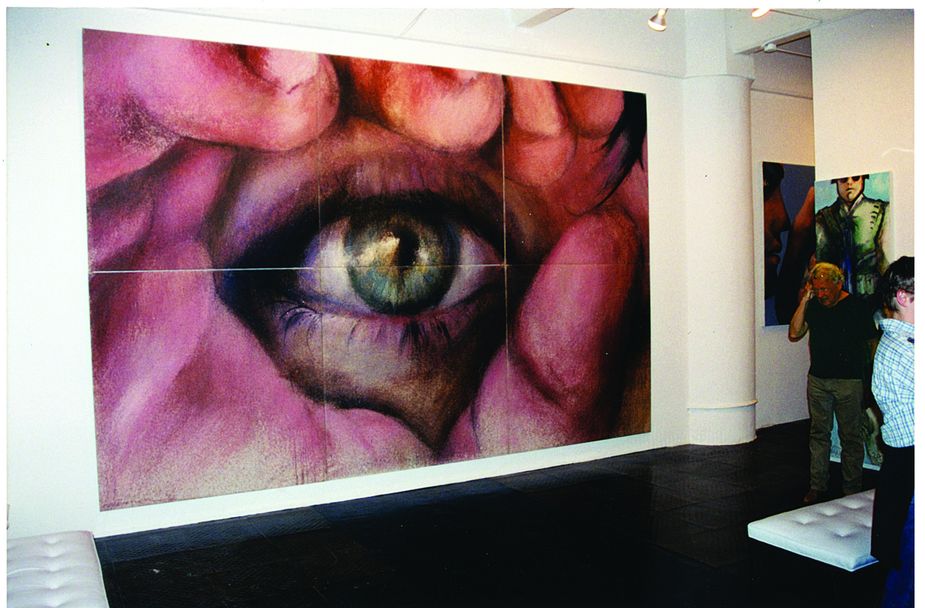

Harold and Warhol collaborated on two of Warhol’s films. They also exhibited together—alongside other luminaries like Robert Indiana, Roy Lichtenstein, and Robert Rauschenberg—in the famous exhibition at the Sydney Janis Gallery titled The New Realists, the 1962 show largely credited with launching Pop Art into the stratosphere and which featured Warhol’s now ubiquitous painting of a Campbell’s soup can. Harold’s contribution? A massive painting of a human hand circling an eye titled Eye of Lightning Billy, a portrait of a character Harold knew in Idabel. Because of Harold’s appearance in The New Realists, he often is referred to as a Pop artist. But his work was notably different from many of his contemporaries and revolutionary in its own way.

Stevenson with one of his most well-known paintings, Eye of Lightning Billy, at the Mitchell Algus Gallery in New York City in 2002. Photo by Ron Clark

During the 1950s and 1960s, Abstract Expressionism was the ascendant art form as it had been since the days of Picasso, Miro, and others. The artists in The New Realists represented a turn away from abstraction.

“What Harold was doing would seem maybe conservative, because he’s painting human figures, but in the context of the 1950s, that was somewhat radical,” says Mark White, executive director of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman, which holds 127 of Harold’s works and artifacts. “The Pop artists are all advocating for this return to realism, a commitment to everyday life. For Harold, that means a return to the human figure, painting life itself. That’s why he’s always associated with Pop Art.”

By the time of his appearance in The New Realists, Harold had begun to live and work largely in Paris, which was where he first conceived of what arguably is his most well-known—and Renaissance-inspired—work.

“He was upstairs in his apartment in Paris, and from the window, he was watching the people walk by on the sidewalk with the gallery over there, and he said, ‘Why do some people go in the gallery and some people don’t?’” says Jordan. “He knew you couldn’t reach everybody, and he said, ‘That’s when I knew I had to paint the big things.’”

What emerged from Harold’s Parisian brainstorm was The New Adam, a forty-foot-long by eight-foot-tall painting of a reclining nude male. The actor Sal Mineo, famous for his Oscar-nominated role in Rebel Without a Cause alongside James Dean, posed for the painting.

“Somebody brought this boy to my studio, and you know, he was very small and very beautifully proportioned,” Harold said in a 1999 interview for the Lower East Side Biography Project. “He said, ‘I’ve never posed for an artist,’ and I said, ‘Well, there’s not much to it.’ . . . I put the poor thing on the dining room table.”

But, White says, Harold’s commitment to depicting the human form in a realistic fashion, as he did in The New Adam, was no passing fad.

“Harold’s work has a substantial influence from an art historical tradition that begins with Greece and Rome but has been reinterpreted by Michelangelo and the artists who followed in his footsteps,” he says. “So The New Adam looks a lot like those monumental nudes that Michelangelo became known for.”

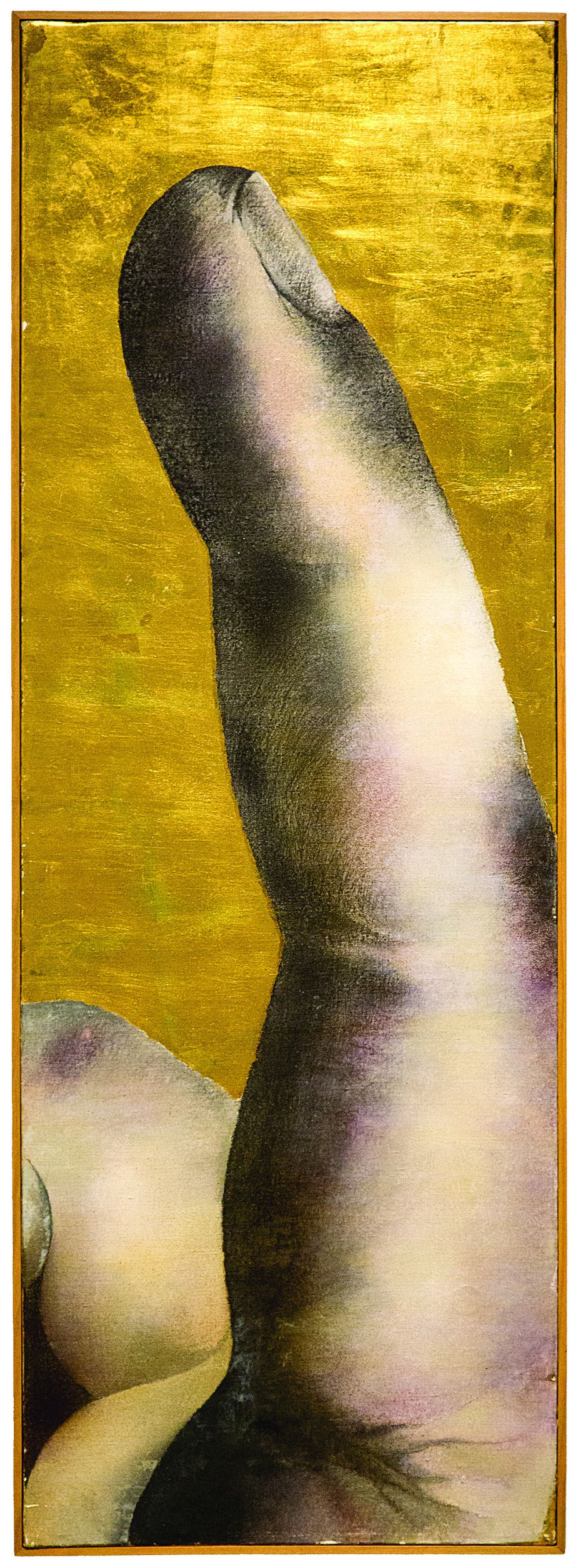

Harold first exhibited Finger of God in Venice in 1962. Though not currently on display, the painting now resides in the Oklahoma City Museum of Art's permanent collection. Photo by Lori Duckworth

Harold had befriended Peggy Guggenheim and exhibited his piece Finger of God during the 1962 Piccola Biennale in Venice, and curators at the Guggenheim in New York invited Harold to display The New Adam in the 1963 exhibition Six Painters and the Object. When they saw the piece, they disinvited him, worried the enormous painting would be a distraction to museumgoers. Eventually, the work caused a sensation when Harold’s agent, Iris Clert, displayed it at her gallery in Paris. Today, The New Adam is a part of the Guggenheim’s permanent collection.

It wasn’t the only time one of Stevenson’s works courted controversy. The same year, the French government gave him permission to hang his forty-foot-tall painting of the famous bullfighter El Cordobés—also a personal friend of the artist and the first athlete ever to earn more than a million dollars—from a platform of the Eiffel Tower. The piece’s visibility created such an enormous traffic jam in the Seventh Arrondissement that the government ordered it taken down. In 1980, he returned to Paris when he took part in the exhibition La Famille des Portraits at the Louvre.

Though Harold and his work traveled the world, it was Idabel that gave him one of his greatest triumphs. In 1966, he received a grant from the Jackson-Iolas Gallery in New York to return to Idabel and paint a series of portraits of the locals, just as he’d done at his downtown studio decades before. What emerged was a hundred-portrait series of Idabel’s people known as The Great Society. Idabel-born artist Poteet Victory, a friend and protégé of Harold’s, watched as he created it and is featured in one of the pieces.

“Nothing was staged,” says Victory. “Whoever would show up, he’d say, ‘Let me paint you.’ Outlaws or in-laws, it didn’t make any difference.”

The oil-on-canvas *Bandits* is part of the permanent collection of the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman. Photo courtesy Ross Dugan Jr. Collection / Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art / University of Oklahoma

Today, ninety-nine of the works that comprise The Great Society are in the collection at the Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art in Norman. The hundredth, the portrait of Victory, hangs in that artist’s Santa Fe studio.

“The Great Society was Harold’s way of celebrating the American character by drawing attention to rural Oklahoma,” says White. “It was his exploration of the fabric of middle America. He wanted you to see their faces and experience their humanity.”

Harold was a prolific painter who counted among his friends the actress and model Edie Sedgwick, the Shah of Iran, and the English peer Jane Heathcote-Drummond-Willoughby de Eresby, whose brother Lord Timothy was, according to many who knew him, the great love of Harold’s life before he was lost at sea in 1963. But Harold spent months at a stretch in Idabel between stints in Paris, New York, Key West, or wherever he happened to be living and working. Still, fame and fortune were never the goal of Harold’s work.

“Art has become a fashionable trade,” he says in the Lower East Side Biography Project video. “I never looked at it that way. I just looked at it as a compulsion I could not escape. I could not avoid it. I couldn’t live without doing it.”

In the video, Harold grimaces when mentioning a friend who hired a publicist to help him become a famous artist. Harold’s distaste for self-promotion in the style of his contemporaries like Warhol may have kept him off critics’ radar in his later career, but he never thought of his work as a conduit to fame and was unimpressed with the fame and fortune of others. This was apparent during his time in New York, when he lived at The Dakota, the building where, in 1981, John Lennon lived and was shot.

“He said one time, he was getting on the elevator, and he asked the other man on the elevator with him, ‘What’s your name?’” says Harold’s niece Caccie Leonard of Idabel. “Harold told me his name was ‘John Lemon or something,’ and I said, ‘You mean John Lennon?’ He didn’t love music. He always wanted complete silence while he was painting.”

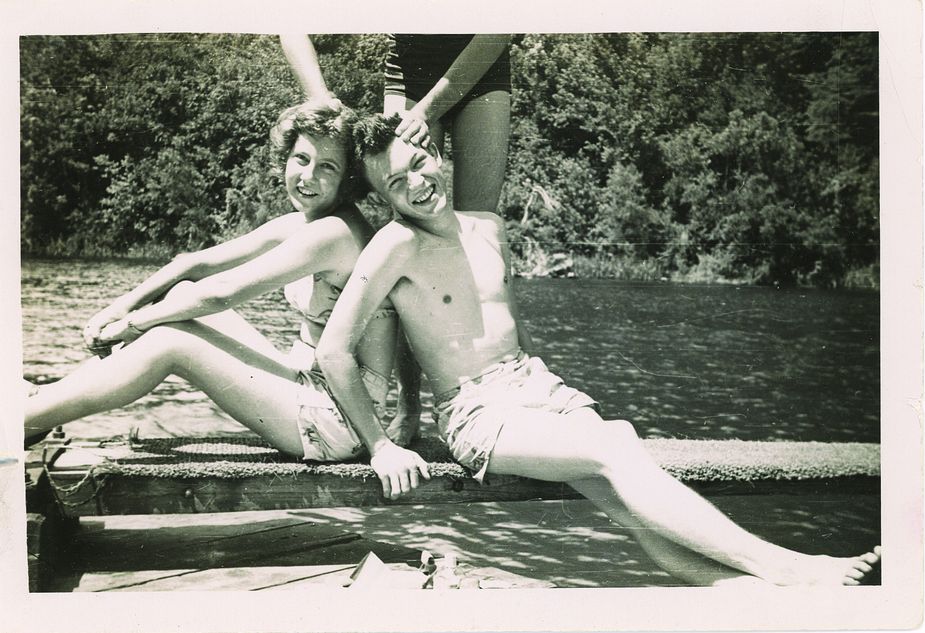

Harold Stevenson and his lifelong friend Alta Fly at a summer arts camp at Broken Bow Lake in the 1940s. Photo courtesy Dian Jordan

Harold’s family in Idabel looked forward to his return trips, though they never knew what kind of trouble their mischievous uncle, whom they called Picasso, might get up to when he was home. Harold’s nephew Kurt Stevenson, who lives in the family home where Harold was born, tells of a particularly harrowing request his “Uncle Picasso” made one summer.

“I was just out of high school, in college, and we always used to go to Phil’s, this beer joint out here north of town, and one day, Picasso says, ‘I want you to take me to Phil’s.’”

Kurt and his now former brother-in-law, Mitch, balked—Phil’s was notoriously raucous, and Harold would stick out. But Harold kept up his harangue, and the pair finally agreed to take him to the honky-tonk, telling the gregarious, five-foot-two Picasso to stay by their side the whole time.

“I’m telling you, I was terrified walking in there,” Kurt says. “Of course, I knew most of those people, but I thought, ‘We’re going to have to cut our way out of this beer joint. This is going to be hell on wheels.’”

After a bit, Harold went missing.

“Mitch said, ‘Where’s Picasso at?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know, they’ve probably got him out back robbing him,’” Kurt says. “We were looking around, and Mitch said, ‘Look. Look.’”

Across the bar, Harold was sitting among a dozen cocktail tables full of bargoers, who were laughing as he regaled them with his stories.

“It was redneck city at these tables, and Harold was leading church up in there,” Kurt says. “I said, ‘Well, it looks like he’s got this under control.’”

Harold lived much of his life with his partner Lloyd Tugwell, a native of the small Choctaw County town of Frogville whom he met in the mid-1960s. When Lloyd died at the pair’s home in the Hamptons in 2005, Harold returned full-time to Idabel. He had purchased the stately home of the county’s first judge, Thomas J. Barnes, but had sold it to the McCurtain County Historical Society. So Harold lived on a ranch south of town, where he continued to paint, entertain guests, and invite his famous friends to visit his cherished hometown.

A few years ago, Harold was diagnosed with dementia. He died peacefully in Idabel on October 21, 2018, leaving behind a massive body of work, a grieving family, a legacy as the most famous artist ever to come from Idabel, and many fond memories among those who knew him.

“He was a very sweet man,” says White. “He was very interested in talking about his experiences, but he did not seem to have a tremendous amount of ego. He didn’t seem wrapped up in his success. Rather, he had a character I’d describe as being very Oklahoman.”

Harold left another legacy behind: That of a man who saw beauty everywhere he looked and wanted to show it to the world. Especially when it came to his hometown.

“Harold never left Oklahoma,” says Kurt. “He says that in interview after interview. He took Idabel with him wherever he went.”

Get There

Museum of the Red River

Harold’s painting Mauro hangs near the museum’s front entrance.

812 East Lincoln Road in Idabel, (580) 286-3616 or museumoftheredriver.org

Barnes-Stevenson House

Harold once owned the house and hosted lavish parties here. Open for tours by appointment. 302 Southeast Adams Street in Idabel, (580) 212-3639 or facebook.com/barnesstevensonhousemuseum

Oklahoma City Museum of Art

Harold’s 1962 painting Finger of God is part of the museum’s permanent collection but not on permanent display. 415 Couch Drive in Oklahoma City, (405) 236-3100 or okcmoa.org

Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art

Ninety-nine of the portraits in The Great Society are a part of this museum’s permanent collection but not on permanent display, as are many of Harold’s other works, letters, and personal effects. The museum is planning an exhibition to honor Harold’s memory.

555 Elm Avenue in Norman, (405) 325-3272 or ou.edu/fjjma

.png)