Hell Came to Tulsa

Published June 2020

By Quraysh Ali Lansana | 28 min read

By Quraysh Ali Lansana

Research by Bracken Klar

If I could stand in the midst of the dead bodies

Of those brave black men who fell in the Tulsa riot and

massacre,

As martyrs to the greatest cause it has ever been human

privilege to espouse,

I would lift my eyes in adoration and gratitude

To the great God of the universe who gave use their being

And my voice to their fellowman throughout this broad

land,

And on behalf of a grateful race pay homage to their

blessed memory.

By way of eulogy it may well be said, that

Because of them, the hope of our race looms brighter

And the world has been made some better,

Not because they lived in it, but because they died as

they did,

True martyrs to a sacred cause!

Fighting against overwhelming odds, and without hope

of surviving the conflict,

These men gave their all that a great principle might

triumph.

Tis better to fight, and die if need be,

Than to live, if to live means to compromise manhood

And to sacrifice the sacred things that life is made of.

from “Eulogy to the Tulsa Martyrs” by A.J. Smitherman

Chimneys, bed frames, and the shells of burned-out buildings were among the few things left standing throughout the neighborhood known as Black Wall Street following the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre. Photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society

The earliest African Americans in Oklahoma Territory arrived on the Trail of Tears with the forced removal of the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole tribes during the 1830s and 1840s. All five of these nations owned African Americans as property, though many Freedmen lived among the tribes, and some blacks and tribal citizens intermarried. The Creeks and Seminoles supported the Union during the Civil War, while the Choctaw and Chickasaw fought on behalf of the Confederacy, and the Cherokee were engaged in an internal conflict over which side to support.

Following the Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, federal treaties granted freedom to enslaved blacks, and these Freedmen were adopted into tribes. These treaties also included large allotted parcels of land. African Americans in Oklahoma and Indian Territory owned more land than anywhere in the nation prior to statehood, including twenty-eight all-black towns starting with Tullahassee, which was founded in 1850. Black entrepreneurship was as important as land ownership in the rise of Tulsa’s Greenwood District.

Extreme racism and deep segregation were the way of things in the midst of Tulsa’s oil boom. While many white Tulsans prospered—and both whites and blacks flocked to the “Magic City”—the business district centered at the intersection of Archer Street and Greenwood Avenue became the hub for the city’s black entrepreneurs and homeowners. A commitment to buying black was critical to the community.

Built in 1905, businessman O.W. Gurley’s grocery store and one-story rooming house served as the catalyst for the growth of other enterprises in the district. Black Wall Street flourished economically and culturally, preceding New York’s Harlem and Pittsburgh’s Hill District communities in black business development and vitality. Though black Tulsans took their political and cultural cues from Harlem and Chicago’s Bronzeville, what they built by their own hands evolved prior to the neighborhoods in those cities. Black Tulsans’ success was rooted in land ownership and a spirit of independence despite hatred both vigilante and legislated.

The American Red Cross set up temporary emergency wards, including this one known as the Maurice Willows Hospital, after the massacre. The Red Cross was the only organization that provided relief to victims of the violence in Greenwood. Photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society

By 1907, the year Oklahoma was granted statehood, “Little Africa,” as it was called by whites, was home to the Tulsa Star newspaper, two black physicians, three grocery stores, and many other businesses and establishments. Schools, churches, and elegant houses dotted the bustling streets. Nightclubs, then Prohibition-era speakeasies, provided venues for the blues and jazz musicians who made Greenwood a regular stop.

By May 1921, Greenwood spanned thirty-five blocks and claimed 11,000 residents. These blocks contained two hundred businesses, more than twenty churches, more than twenty restaurants, thirty grocery stores, two movie theaters, two newspapers, six private planes, one bank, one post office, a library, a bus system, schools, and law offices.

The political climate in the nation during the early twentieth century was a complex mixture of volatility, uncertainty, and patriotism. Nearly 4.7 million Americans fought in World War I, including more than 350,000 African Americans. Though black people were allowed to serve in the United States military, they worked largely in segregated units.

But the Second Industrial Revolution already was transforming American society by the time the war began in 1914. The expansion of steel, electricity, and petroleum jobs led to accelerated urbanization and the first of two significant migrations of African American people as blacks were recruited to leave the South for work in Northern cities. The large number of African Americans in Chicago, Philadelphia, and elsewhere gave rise to great anxiety among many white people, who feared their shelter, jobs, and safety were at risk. The end of the war in 1918 and state-side efforts to unionize black workers did not diminish these concerns.

Few photos exist of Greenwood prior to the massacre. This north-facing view shows the neighborhood in 1917. Photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society

African American veterans came home to more severe racism and rampant lynching than they’d left behind—but with a new resolve to battle segregation. Many whites saw them as a threat to the status quo of Jim Crow laws. Twenty-five riots, eighty-three known lynchings, and the massacre of two hundred African Americans in Elaine, Arkansas—a mere six hours from Tulsa—occurred between April and October of 1919. The Red Summer, as this period is known, was a time of brutal assaults generally initiated by rogue white civilians and veterans upon black veterans. These white servicemen had help from a reinvigorated Ku Klux Klan, and their victims also included African American women and children. Tulsa’s city government contained many Klan members, and the city was a buzzing hive of KKK activity, inflaming racial tensions.

Nineteen-year-old Dick Rowland shined shoes at the Ingersoll Recreational Parlor at Third and Main streets. The owner arranged for his employees to use the bathroom on the top floor of the Drexel Hotel across the street. Elevator operators usually were white women, and seventeen-year-old Sarah Page ran the lift at the Drexel.

John D. Mann owned Mann’s Grocery store in the 1920s, which was located at 820 North Greenwood Avenue prior to being burned down. He relocated to King Street after the massacre. Photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society

“One Monday noon, the 30th of May, he came running home, breathless, and said that the police were after him for what had just occurred,” said Dick’s aunt, Damie Rowland Ford. She cared for the young orphan and told his story in a 1972 audio recording that was transcribed in the book 1921 Tulsa Race Riot and the American Red Cross, “Angels of Mercy:” Compiled from the Memorabilia Collection of Maurice Willows, Director of Red Cross Relief by Bob Hower and Maurice Willows. “He had just delivered some shoes upon the third floor of the Drexel building to a customer, had used the restroom, and when leaving, he got into Sarah Page’s elevator to go back down. But she hadn’t gotten the elevator even with the floor, so he tripped and stepped on her instep. She was so mad at him for hurting her foot that she pounded him again and again on the top of his head with her leather purse, vigorous enough to break off its handles. He said, ‘I reached up to hold her arms back and prevent her from pounding my head, and held them there. When the elevator reached the ground floor lobby, Sarah screamed, ‘I’ve been assaulted!’”

When a clerk from the nearby Renberg Clothiers tried to nab Rowland, he fled.

“I outran him and fled here,” Rowland said to Aunt Damie once he got to her home. “I’ve gotta hide until tomorrow.”

Rowland was arrested and jailed the next day, the same day the Tulsa Tribune carried a headline on its front page that read, “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator.” The Tribune also published an editorial with a headline that read, “To Lynch Negro Tonight,” though the piece was pulled before the print run was completed. By dinnertime, a crowd of more than three hundred whites had gathered at the courthouse where Rowland was held. Sheriff Willard McCullough, after ordering three white men to leave the building, commanded the mob to disperse. A group of twenty-five to thirty black men gathered in Greenwood, all armed, and went downtown to defend the jail. The police told them Rowland was safe, and they left. The white men lingered, and several attempted to break into the armory for rifles and ammunition. By 10 p.m., an estimated 1,500 white men were in front of the courthouse. Hearing of this, seventy-five black men returned.

Barney Cleaver, Tulsa’s first black police officer, pleaded with his fellow Greenwood residents to leave. As they prepared to retreat, a white deputy approached a black veteran and demanded his Army-issue .45-caliber pistol.

“Like hell I will,” the veteran answered.

The men struggled. A shot was fired.

And so it began.

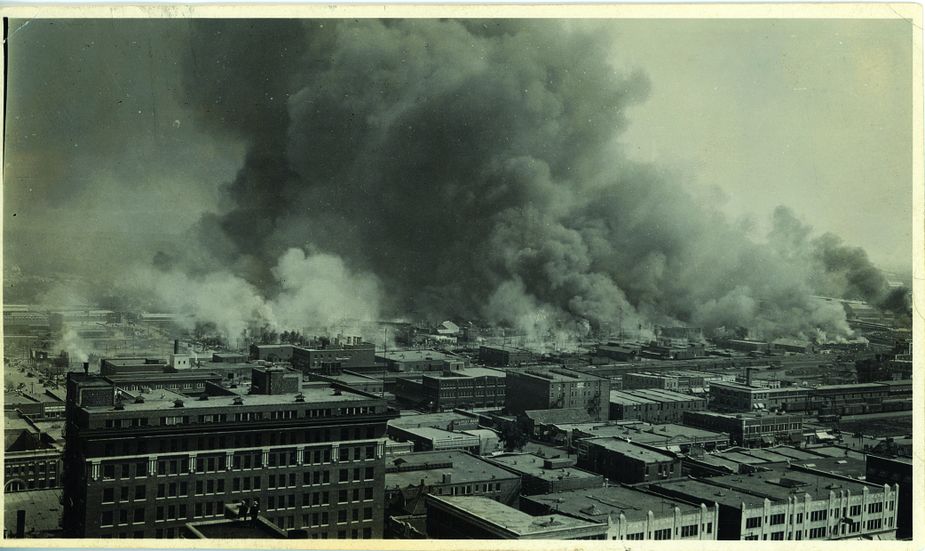

This photograph was taken from the roof of what was then the fourteen-story Cosden Building in downtown Tulsa—now the Mid-Continent Tower—during the Tulsa Race Massacre. Photo courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society

The NAACP’s Walter White reported that twelve people were shot in the exchange outside the courthouse, including a black man whom the white vigilantes refused to allow white doctors to assist. Through the gunfire and chaos, the outnumbered black citizens retreated to Greenwood as the Tulsa police deputized throngs of white men. A light-skinned black man who could pass for white attended a meeting of these special deputies then made his way home to alert the community of the planned invasion. White men, led by local public officials, broke into hardware stores and pawn shops to steal guns and ammunition on their way to Little Africa. The first fire took place at the corner of Archer Street and Boston Avenue, the western border of Greenwood, at 1:30 in the morning on June 1. Hundreds of white men shot at the local fire department, forcing firefighters to flee the scene, preventing them from putting out the fires to come.

From there, hell came to Greenwood. One anonymous eyewitness later told black journalist and author Mary E. Jones Parrish about the violence. She published the account in her 1922 book Race Riot 1921: Events of the Tulsa Disaster.

"When I fully realized what was happening, I saw men and women fleeing for their lives, while white men by the hundreds pursued them, firing in all directions. As one woman was running from her home, she suddenly fell with a bullet wound. Then I saw aeroplanes, they flew very low. To my surprise, as they passed over the business district, they left the entire block a mass of flame. I saw men, women, and children driven like cattle, huddled like horses, and treated like beasts . . . I saw hundreds of men marched through the main business section of ‘White Town’ with their hats off and their hands up, with dozens of guards marching them with guns, cursing them for everything mentionable. I saw large trucks following up the invaders as they ran the colored people from their homes and places of business. Everything of value was loaded on these trucks, and everything left was burned to ashes. I saw machine guns turned on the colored men to oust them from their stronghold. Tuesday night, May 31, was the riot, and Wednesday morning, by daybreak, was the invasion."

A contemporary view of Greenwood and downtown Tulsa. Photo by Shane Bevel

Black Tulsans had to choose between fight and flight. Many blacks defended their property in gun battles with the heavily armed white mob. Others fled—or attempted to flee—in cars and on foot. Some had little to no idea how their lives were about to be horribly changed. Greenwood resident Kenny I. Booker was eight years old at the time.

"At the time of the Tulsa race riot of 1921, my parents and the five of us children lived at 320 North Hartford Avenue. We had a lovely home, filled with beautiful furniture, including a grand piano. All our clothes and personal belongings—just everything—were burned up during the riot. Early on the morning of June 1, 1921, my parents were awakened by the sounds of shooting and the smell of fire, and the noise of fleeing blacks running past our house. My dad awakened us children and sent us to the attic with our mother. We could hear what was going on below. We heard the white men ordering dad to come with them; he was being taken to detention. We could hear dad pleading with the mobsters. He was begging them, ‘Please don’t set my house on fire.’ But, of course, that is exactly what they did just before they left with dad. Though dad went outside the house with the mobsters, he slipped away from them when they got preoccupied splashing gasoline or kerosene on the outside of the house to speed up the burning. He rushed to the attic and rescued us. We slipped into the crowd of fleeing black refugees. Thank God we did not burn up in that attic!"

Ernest Gibbs, also a Greenwood resident, was not yet twenty that day.

"A family friend came from a hotel on Greenwood where he worked and knocked on our door. He was so scared he could not sit still, nor lie down. He just paced up and down the floor talking about the ‘mess’ going on downtown and on Greenwood. When daylight came, black people were moving down the train tracks like ants. We joined the fleeing people. During this fleeing frenzy, we made it to Golden Gate Park near Thirty-sixth Street North. We had to run from there, because someone warned us that whites were shooting down blacks who were fleeing along railroad tracks. Some of them were shot by whites firing from airplanes. On June 1, 1921, we were found by the guards and taken to the fairgrounds. A white man who Mother knew came and took us home. Going back to Greenwood was like entering a war zone. Everything was gone! People were moaning and weeping when they looked at where their homes and businesses once stood. I’ll never forget it. No, not ever!"

Tulsa police used private planes to patrol the city and almost every significant black community in northeastern Oklahoma both during the massacre and in the days that followed. However, it is unclear who was at the controls of the plane that dropped dynamite and kerosene bombs on the district. Genevieve Elizabeth Tillman Jackson was almost six years old at the time.

"I saw what I thought were little black birds dropping out of the sky over the Greenwood District. But those were no little birds; what was falling from the sky over the Negro district, as it was called in those days, were bullets and devices to set fires, and debris of all kinds. Mother, sensing the danger, ran out and got me and took me into the house. I saw a truckload of dead bodies being carried somewhere. I was just spellbound looking at those bodies—bodies that looked like they had just haphazardly been thrown onto that truck, with arms and legs just dangling. I got closer so I could see better and I noticed that the faces and arms were black but that when the arms dangled, a person could see white at the top of the arms. I asked about that. I learned later that those were white men who had painted their faces and arms black so they could get into the Greenwood community under false pretenses. But when they started shooting down the black people, their game was up and they, themselves, got shot down. Many other black riot victims told of white bosses who had cots, blankets, and food already in place at their homes and businesses just waiting for their black employees when the riot broke out. They had to know that the riot was coming."

A variety of local businesses have made the area a busy commercial district once again. Photo by Shane Bevel

Many white Tulsans knew of the invasion prior to its execution. This was not the case for hundreds of black Tulsans. Another survivor, Otis Granville Clark, reported that he was caught in the middle of the riot.

"Some white mobsters were holed up in the upper floor of the Ray Rhee Flour Mill on East Archer, and they were just gunning down black people, just picking them off like they were swatting flies. Well, I had a friend who worked for Jackson’s Funeral Home, and he was trying to get to that new ambulance so he could drive it to safety. I went with him. He had the keys in his hand, ready for the takeoff. But one of the mobsters in the Rhee building zoomed in on him and shot him in the hand. The keys flew to the ground, and blood shot out of his hand, and some of it sprayed on me. We both immediately abandoned plans to save that ambulance! We ran for our lives. We never saw my stepfather again, nor our little pet bulldog, Bob. I just know they perished in that riot. My stepfather was a strong family man. I know he did not desert us. I just wish I knew where he was buried."

An estimated three hundred black Tulsans perished in the two days of racist carnage. More than a thousand homes were destroyed by bombs and arson. More than six thousand black citizens were forced into internment camps at Convention Hall, public buildings downtown, McNulty Park, or the Tulsa Fairgrounds, where they were held under armed supervision for six days. At first, blacks only were allowed to leave the camps if a white person vouched for them. Under martial law, blacks who were not interned had to carry green cards with the words “Police Protection” on one side and personal information on the other. Those who stayed in Tulsa slept in tents provided by the Red Cross on the land where their homes and businesses had stood.

A sign commemorates many of the businesses that have operated in the district. Photo by Shane Bevel

The first revival of Greenwood was initiated very soon after its destruction, despite vocal resistance from white Tulsans which was amplified by the Tribune. Black churches, including Mount Zion Baptist, Vernon Chapel A.M.E., and First Baptist of North Tulsa, provided the backbone and foundation for this rebirth. The law firm of Spears, Franklin, and Chappelle worked on behalf of black Tulsans from a tent on Archer Street. Attorney B.C. Franklin—father of noted historian John Hope Franklin—and his partners presented more than $4 million in claims against the city and several insurance companies. No one who lost property in the massacre, including whites, received restitution from insurance companies, as civil disturbance was not covered. Spears, Franklin, and Chappelle argued successfully against a city ordinance that would have made rebuilding in Greenwood unaffordable for most residents. By 1922, many entrepreneurs had opened stores and businesses in the district.

Today, as Tulsa prepares for the massacre’s centennial, the city is engaged, for the first time, in the search for mass graves from the tragedy. Three possible sites have been identified, and soil collection at Rolling Oaks Cemetery has merited a plan for excavation. The massacre and its history were not formally taught in public education settings until 2020. The work of the Tulsa Race Riot (Massacre) Commission, the Greenwood Cultural Center, and the John Hope Franklin Center for Reconciliation, among other entities, scholars and activists, has kept the story alive.

Still, more Oklahomans likely are unfamiliar with the massacre than the number of those aware of it. Some Tulsans, both black and white, remain conflicted about revisiting those shamefully violent days.

A visitor explores John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park. Photo by Shane Bevel

Black Wall Street, as it now is known, is in the midst of a third renaissance. The storefronts at Archer and Greenwood are mostly active, with black-owned businesses, restaurants, and stores thriving. The upcoming centennial has attracted both national and international attention and inspired new books, films, and television shows—most notably HBO’s series The Watchmen, which was set in present-day Tulsa but focused heavily on what happened in Greenwood in 1921.

As Mary E. Jones Parrish observed in Race Riot 1921, “The Tulsa disaster has taught great lessons to all of us, has dissipated some of our false creeds, and has revealed to us verities of which we were oblivious. The most significant lesson it has taught me is that the love of race is the deepest feeling rooted in our being, and no race can rise higher than its lowest member.”

Zarrow Mental Health Symposium—Healing from Historical Trauma

› This two-day symposium will feature speakers including Cornel West.

› October 1-2 at Tulsa’s Cox Business Center

› zarrowsymposium.org

.png)