Liquid History

Published October 2022

By Mason Whitehorn Powell | 6 min read

Since taking his first photographs in 1962, Gaylord Oscar Herron has communicated in a visual language equally balanced between people and the cities they inhabit. He describes this as being summoned to a picture, and this mindset lends a naturalness to his work that feels both fateful and inspired.

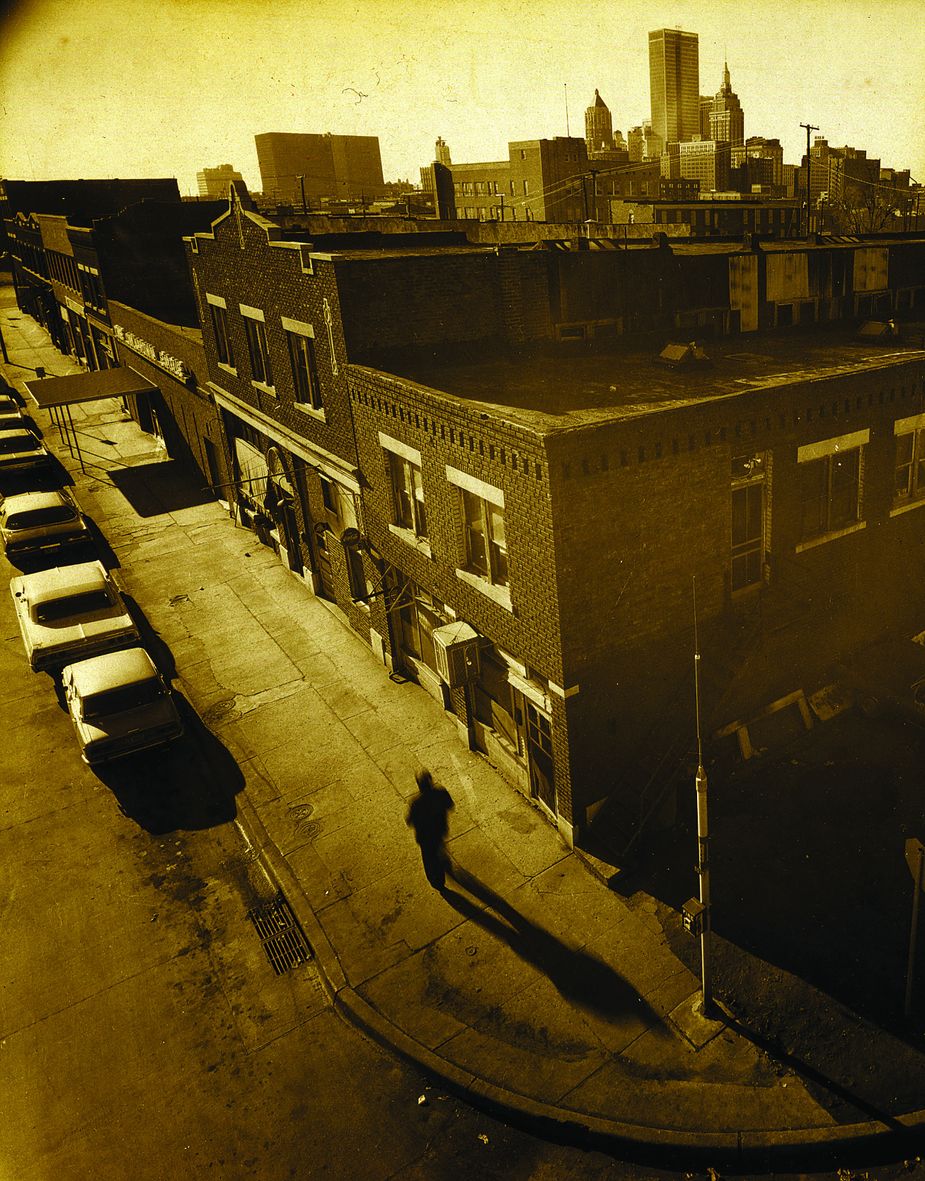

A view of downtown Tulsa from Greenwood, 1972 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

“Photographers are always accused of finding a picture, nailing it, making a print, and making it available—but they don’t find the picture, the picture finds them,” Herron says. “That’s the thing that I’ve realized recently. The picture is calling you to examine it, to engage with it, and then to maybe even record it, to be a watcher. To be a recorder of visual history, which is like liquid history, like a stream or a river running fast, you reach in and pull out a little drop. It’s as if the picture, the location, and the event come to you and demand that you accept them.”

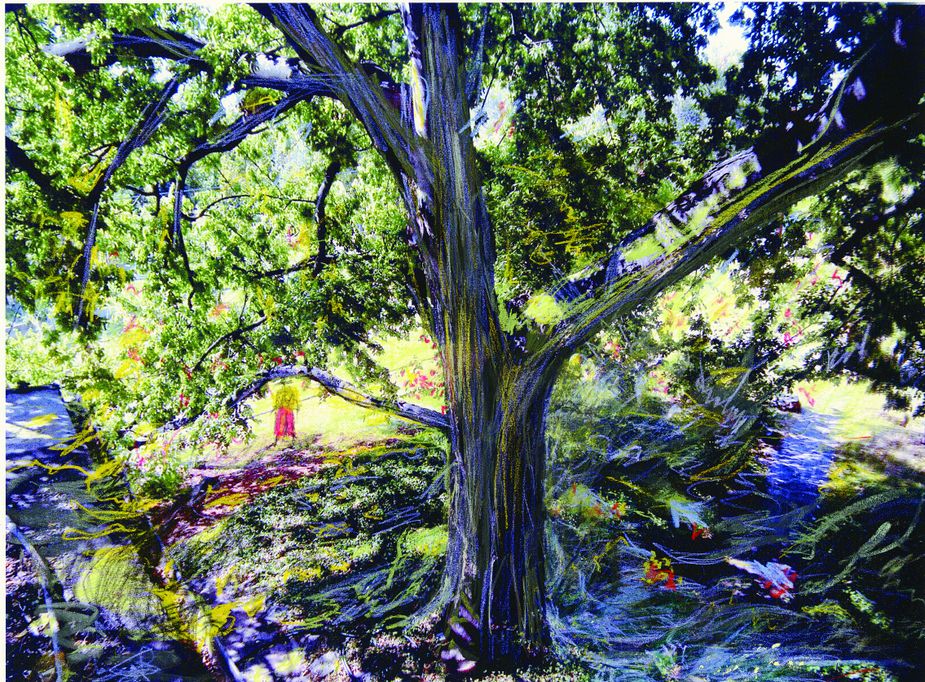

In recent years, Herron has started creating photo illustrations—drawing over photographs with colored pencils—like he's done here with this view looking west on East Eleventh Street. Photo by G. Oscar Herron

Known to most Tulsans as G. Oscar, Herron owns and operates a bicycle shop, G. Oscar Bicycles. Located on Main Street just south of downtown, the space is filled with new and vintage bikes. Herron’s photographs line the walls alongside vintage product containers, other historic photos of Tulsa and the world, and bike repair tools.

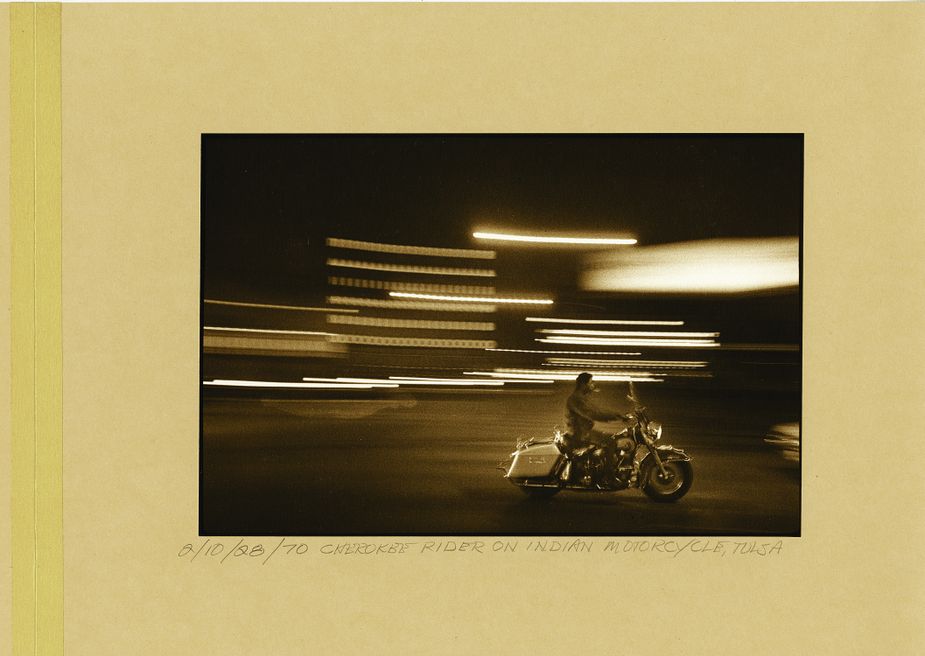

A man rides an Indian motorcycle through Tulsa, 1970 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

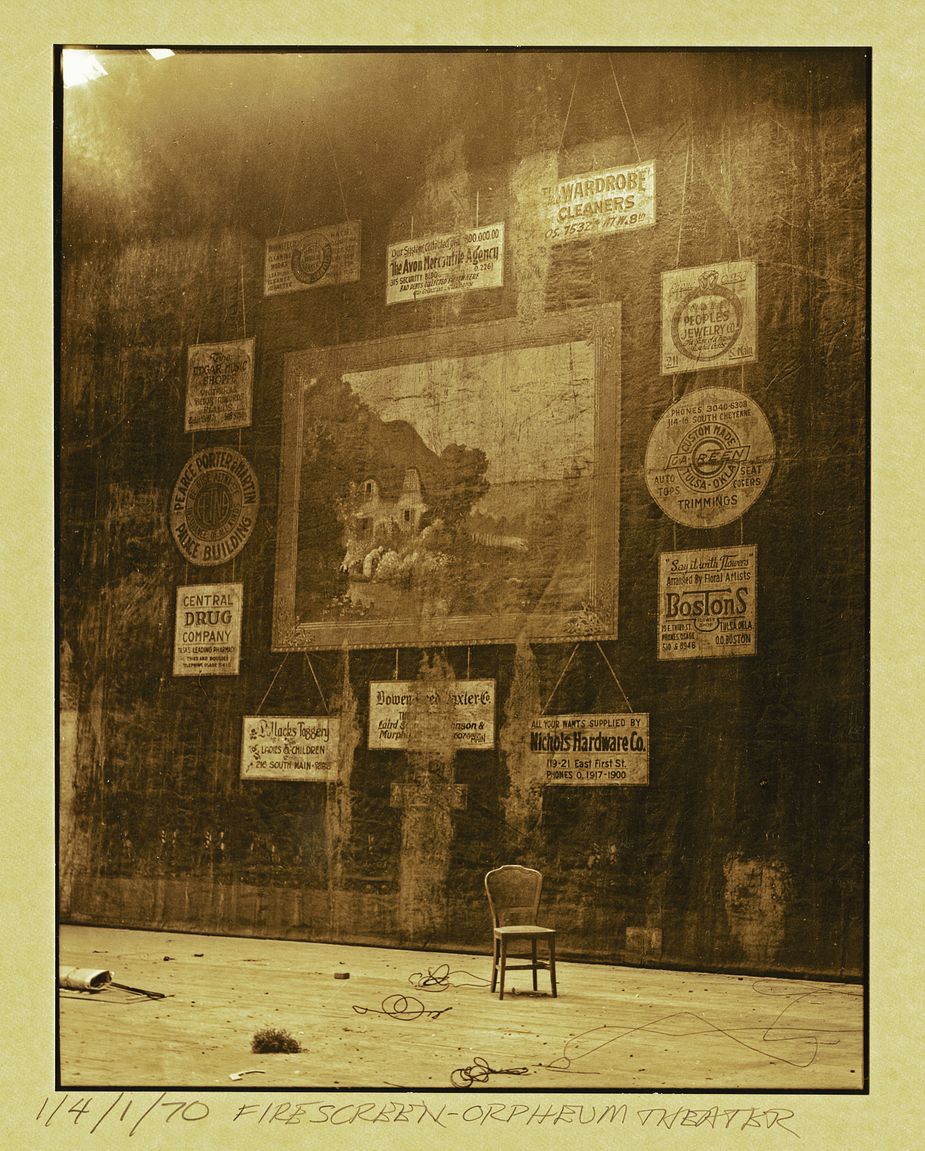

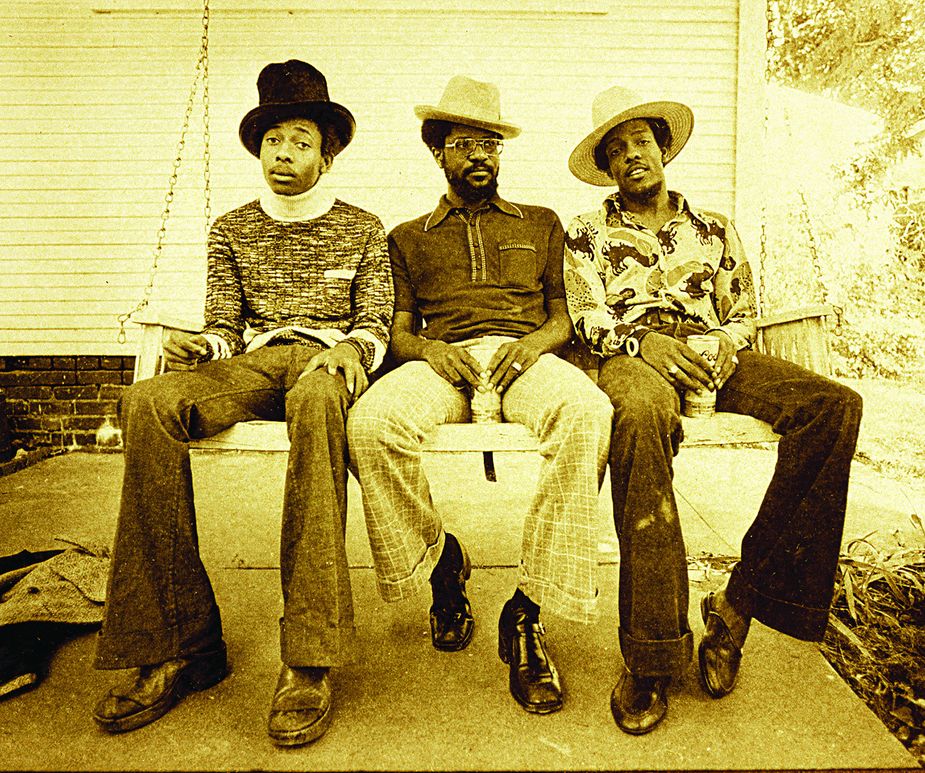

After returning from military service in Korea in 1964, Herron began taking photographs around Tulsa, though his intent was not to document the city’s history. The importance of his work lies not only in its artistic merit but the fact that many of the people and places Herron encountered now are gone. His Tulsa is dreamlike but rendered honestly and without nostalgia.

The fire screen at the Oprheum Theater, 1970 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

“My literal language, my vocabulary is in these pictures,” he says. “This is how I communicate. I don’t communicate with words. The photographs become the language, my syntax, so you can read me like a book—it’s easy—just look at the pictures.”

The GAP Band, 1974 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

Herron’s recent focus has been on the old-growth trees of Midtown Tulsa. He selects a photograph and goes over it with colored pencils, adding texture and erasing human traces such as cars and telephone poles. Herron says he hopes to restore these scenes to pre-Industrial Revolution landscapes. The results are lush and swirling with colors; his overdrawings meld perfectly with the obscured suburban backdrops.

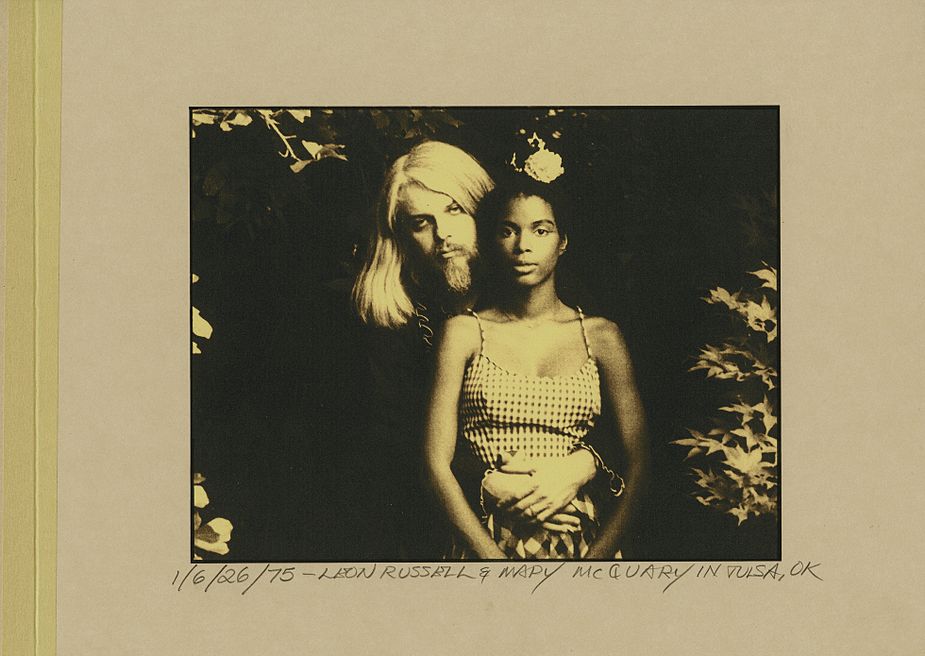

Leon Russell and Mary McCreary in Tulsa in 1975, the year they were married. Photo by G. Oscar Herron

A focus on trees is not unprecedented in his work, some of which are included in the Smithsonian’s collection. Herron has documented the Creek Council Oak Tree, sacred to the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and the tribe’s remaining “signal trees,” in addition to the trees that lined the Arkansas River where the Gathering Place now sits. Just as Herron photographed a Tulsa that’s been lost to time, now he’s restoring it to an earlier age.

Herron's newer works often depict current Tulsa locations with some signs of human habitation removed. Photo by G. Oscar Herron

Herron describes nature as “God’s perfect art.” Tulsa, once the wild crossroads of several Native American tribes, came to represent an oil economy at odds with the natural world as people distanced themselves from the environment.

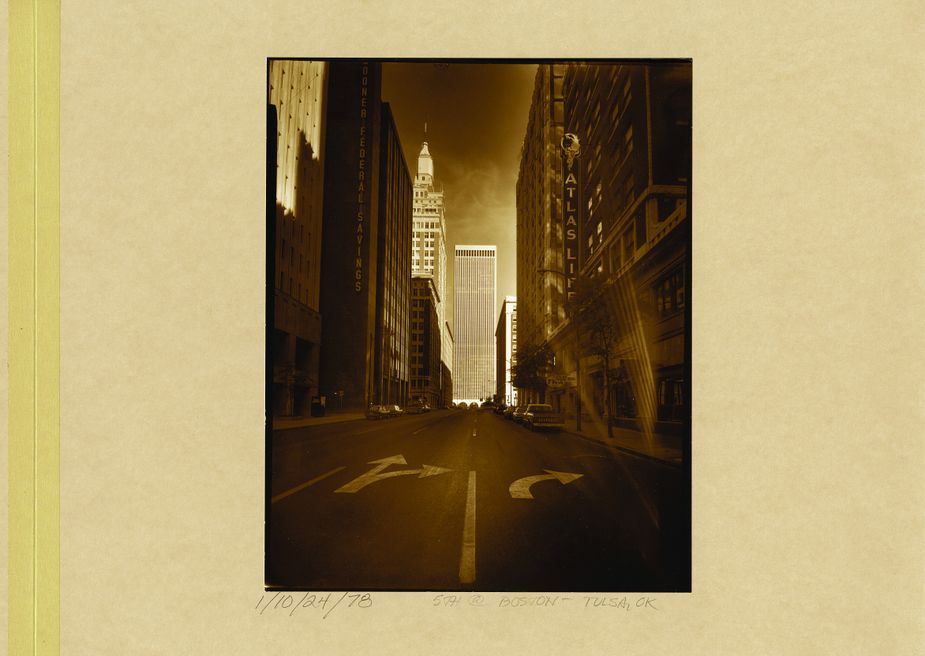

Boston and Fifth Avenues in downtown Tulsa, 1978 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

“I need to feel a certain kind of movement in the lens, in the trees, in all of the elements,” he says. “So it needs to dance on the page to make me happy. If it doesn’t do that, it’s just another dull rectangle. It’s got to have a dance of its own inside.”

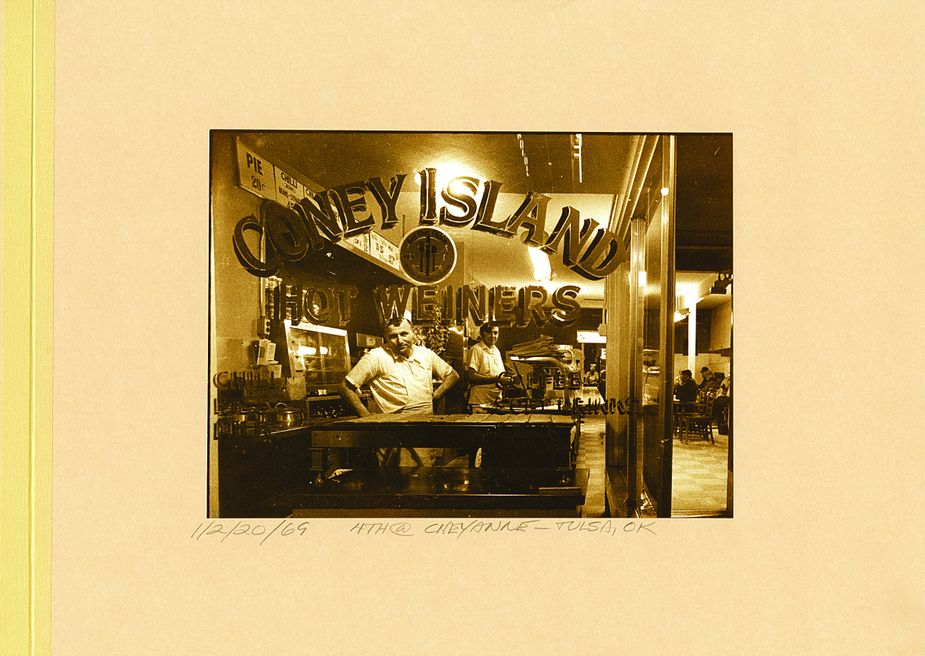

Coney Island restaurant, 1969 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

Boston and Fifth Avenues in downtown Tulsa, 1978 Photo by G. Oscar Herron

(1).jpg)