Lone Wolf of the Canadian

Published May 2020

By Jim Logan | 22 min read

When former President George W. Bush addressed an outdoor throng of nine thousand people gathered for Woodward’s 2009 Fourth of July celebration, he spoke of one of that community’s early citizens who had inspired him. The two men shared much in common: Both were Texas raised, both had famous fathers and ties to the Governor’s Mansion in Austin, both struggled with alcohol, and both loved and married women named Laura.

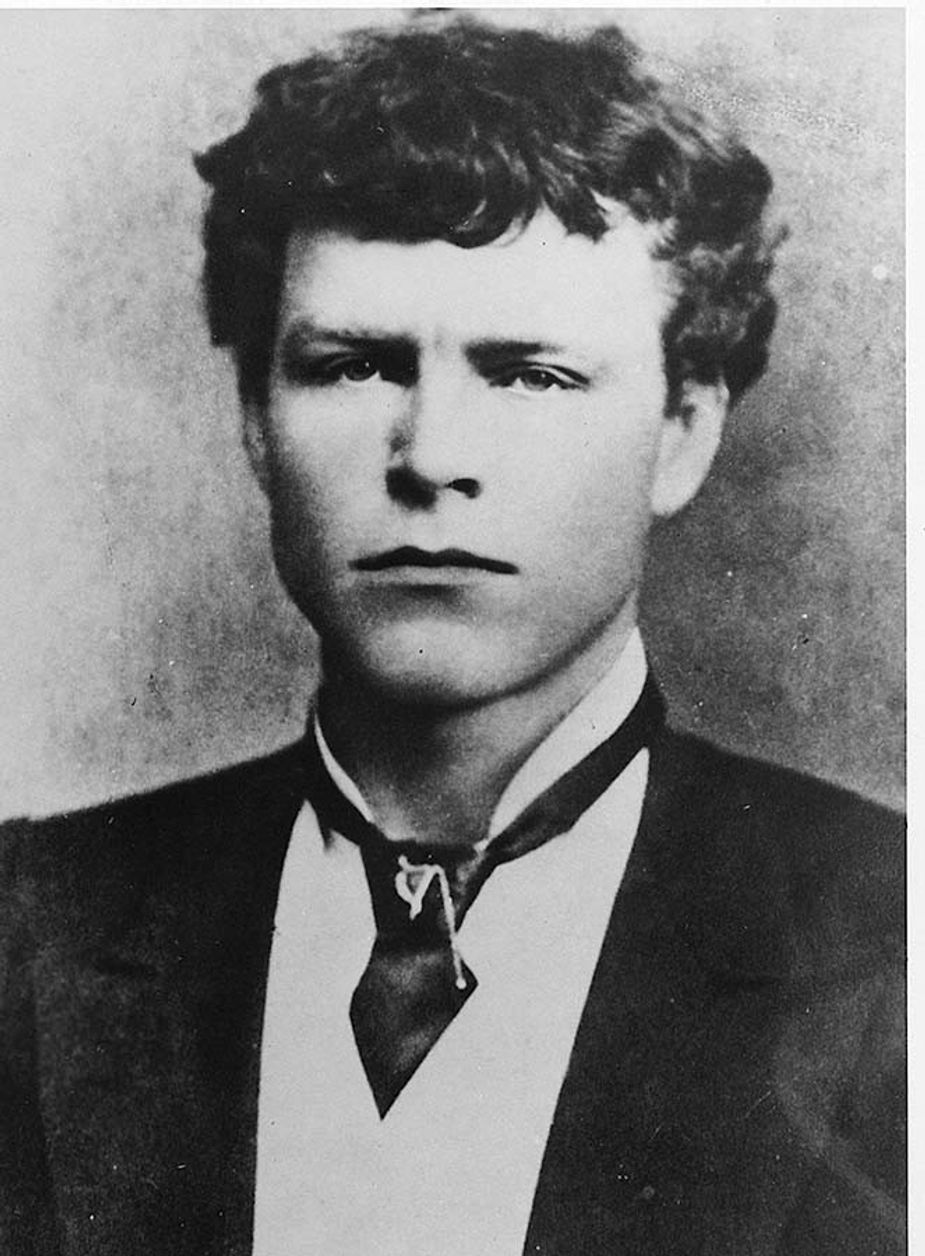

The life that ended in August 1905, two years before Oklahoma achieved statehood, was among the most remarkable to emerge from the American West. The man spoke Spanish, French, Latin, and seven Indian dialects. He quoted the Bible, Greek scholars, and Shakespeare in the course of his work and was, upon his death at forty-five, recognized as one of the finest trial lawyers in the country.

Statuesque, articulate, temperamental, fast with a gun, and overly fond of whiskey, he inspired two biographies and a 1960s television western series bearing his name. A central character in one of Edna Ferber’s epic novels was based on his life, as were two Hollywood movies, one of which would win the 1931 Academy Award for best picture.

An Old West original who died young, Temple Lea Houston was quick on the draw and even faster to wield his oratorical skills in defense of his clients. Photo courtesy Texas State Library & Archives.

Temple Lea Houston, the youngest child of Texas governor Sam Houston, was born in 1860, when the latter was sixty-seven. His father died three years later, and yellow fever took his mother when he was seven. Described by biographers Glenn Shirley and Bernice Tune as an assured, strong-willed youngster with his father’s build and temperament, he was raised by an older sister.

At thirteen, skilled with horse, rope, and gun, he signed on with a cattle drive, drawing a grown man’s wages. From Great Bend, Kansas, he headed for Dakota Territory—night-clerking aboard a Mississippi River steamboat—then back down to New Orleans, where a family friend helped him become a Senate page in Washington. For three years, he observed the country’s finest orator-statesmen, honing his skills in debate before returning home to Texas to attend A&M and later Baylor University. There, he completed four years of study in nine months, graduated with honors, and became the state’s youngest attorney at age nineteen.

From a beginning law practice in Brazoria, Texas, his trial work achieved wide acclaim. Within two years, he was appointed by the governor as attorney for the thirty-fifth judicial district, a sprawling, twenty-six-county swath of the Texas panhandle. Formerly home to Kiowa, Comanche, and the Goodnight cattle empire, the area was home to an assortment of buffalo hunters, cowboys, rustlers, and horse thieves. In a letter Houston wrote to his wife, he described his Mobeetie, Texas, headquarters as “a bald-headed whiskey town with few virtuous women.”

Owned by Fred Shaeffer of Norman, this dresser was part of a five-piece bedroom set that once belonged to Temple Houston. Prior to that, it was General George Custer’s. Photo by Steven Walker.

Six-foot-two, auburn-haired, and with piercing gray eyes, young Houston was an imposing figure. A friend once described him as “handsome, brilliant, and charming…a perfect model of physical manhood.” He also was fearless, with a flair for the dramatic. Conspicuous attire—a day’s dress might include a buckskin shirt, caballero pants, a widebrimmed sombrero with a silver eagle in its crown, his father’s miniature gold saber pin, and a pearl-handled revolver— made him hard to miss.

He won numerous public shooting contests and was considered one of the most formidable gunmen in the West. A contemporary once wrote, “Temple Houston stays alive because he’s very fast on the draw. He has winged several bad men and killed two or three, and now he is a man to be feared.” Rumors flew that he’d beaten Bat Masterson and Billy the Kid in a shooting match. Outlaws gave him a wide berth.

He gained wide notice at twenty-one with a speech at the unveiling of the San Jacinto Monument to heroes of the 1836 Texas victory over Santa Anna. His closing words visibly moved the crowd: “They will be here but a little while longer…Cling tenderly to these old men, for when they are gone, nothing like them is left.”

The Colt .45 Houston used during the Jennings shootout. Photo by Johnny McMahan.

Before taking the panhandle post, he’d met Laura Cross, the pretty young stepdaughter of a Texas cotton grower. She would later recall in a 1936 Houston Post article, “I saw him across the room, and he saw me. I guess it was love at first sight, all right, for we were both goners.” They were married on Valentine’s Day in 1883.

Houston served two terms in the Texas legislature. At twenty-eight, he was chosen to deliver the dedication speech for the new State Capitol building in Austin. After leaving the senate and losing a bid for the Texas Attorney General’s office, he became legal counsel for the Santa Fe Railway and moved his family to the town of Canadian, in the northeastern part of the Texas panhandle.

Temple Houston was drawn to Oklahoma for the same reasons his father had left Tennessee for Texas—it was a young country full of opportunity and looking for law, order, and statehood. After watching the Cherokee Strip Land Run from a Santa Fe boxcar, he opened a law office on Main Street in the new settlement of Woodward, Oklahoma Territory, in fall 1893. Almost a year later, his family joined him to make it their home.

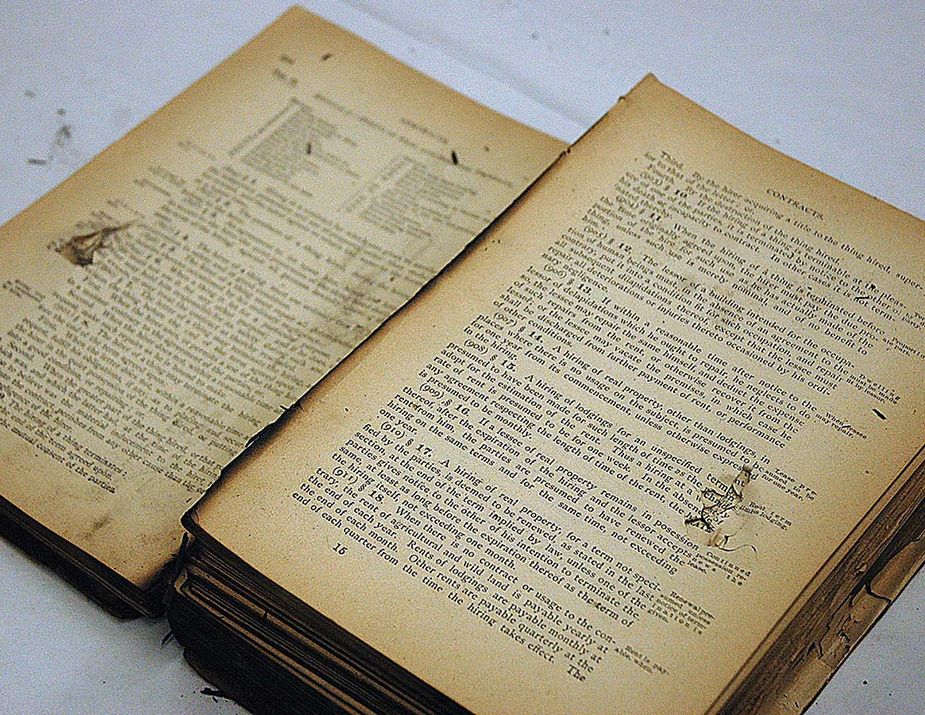

The book of territorial statutes that saved Temple Houston’s life. Photo by Woodward News.

Downstream from Fort Supply on the North Canadian River, Woodward was a bustling mass of settlers, soldiers, railroaders, cattlemen, and gun-toting cowboys—a smaller version of Dodge City. It was for a time the largest point of original cattle shipments in the world, with two banks, two newspapers, and twenty-three saloons. Most legal cases involved land titles, most of the citizenry carried firearms, and community meetings often ended in gunfire.

Houston, widely regarded as one of the best defense attorneys in the nation, left his mark on the territorial courtrooms of Oklahoma. Representing clients and causes popular and otherwise, he packed and polarized courtrooms with standing-room-only crowds.

Houston brought photographic recall, humor, passion, and deep human insight to the court. He was the model for the lead character, Yancey Cravat, in Edna Ferber’s acclaimed 1929 novel, Cimarron. A newspaper of the day, the Guthrie Daily Leader, dubbed him “the silvertongued orator of Oklahoma.”

Once assigned to defend a hapless horse thief, he told the judge he’d do all he could for the defendant and met privately with the man in a closed room. When authorities, after a lengthy wait, opened the door to find Houston sitting alone with an open window nearby, he said, “Well, boys, I gave him some good advice.”

A line drawing by Houston. Photo courtesy of The Plains Indians & Pioneers Museum.

While known for keeping powerful cattle ranchers out of prison, Houston championed many a worthy cause. He once shot up a Guthrie saloon after it fleeced a youngster out of his wages, chased the gamblers and the establishment’s owner from the building in a rage, and returned the boy’s money.

For theatrics, nothing topped his defense of a young cowboy who allegedly stole a rancher’s horse. When accosted by the rancher, known as a quick-tempered gunman, the cowboy, according to witnesses, shot and killed the rancher without giving him a chance to draw. Before a hostile jury, Houston pled self-defense for his client and set about showing how the dead man’s reputation and “lightning draw” left the defendant no chance in a fair fight and no choice but to fire first.

Inching slowly closer to the jury box, he described his client as “an ordinary, hard-working citizen...little experienced in the use of firearms.” Stopping just in front of the jurors, he explained how the rancher had been “so adept with a six-shooter that he could place a gun in the hands of an inexperienced man, then draw and fire his own weapon before his victim could pull the trigger—like this!”

He then drew the Colt pistol from beneath his coat, pointed it at the jurors, and began firing rapidly—with blanks. Chaos followed, with jurors, judge, defendant, and panicked spectators stampeding for cover and out of the building.

When order returned, the judge threatened the attorney with a contempt citation. Houston apologized for “any seeming disrespect for the person of this court,” explaining that he wanted to “show what speed this dead man possessed.”

The reassembled jury, angered, found Houston’s young cowboy guilty. He then motioned for mistrial, based on the jury’s separation and mingling with the crowd during the hearing. A new trial was grudgingly granted, and a few months later, with an impartial jury and new presiding judge, his client was acquitted.

Among Houston’s foremost legal rivals in Oklahoma Territory were the Jennings brothers: Ed, John, Frank, and Al, all lawyers. Their father, J.D.F. Jennings, was a local judge. In October 1895, Houston opposed Ed Jennings in a controversial property case. Tempers flared in court, with Houston pronouncing his opponent “grossly ignorant of the law.” Ed Jennings yelled, “You’re a damn liar,” and attempted to slap Houston. Guns were drawn, the two were separated, and the case was adjourned until the next day.

Houston’s grave in Woodward. Photo by Woodward News.

That evening, as Houston and a friend sat in a saloon, Ed Jennings and his brother John approached their table. An argument erupted. Houston asked Jennings to step outside. Jennings said they could settle it inside, and each man drew his gun. Blasts from the first of several shots shattered the lights.

It is generally believed that Houston killed Ed Jennings with a shot to the head, although some believe a wild shot in the dark from John is what killed his brother. John Jennings was also badly wounded in the arm. With witnesses claiming Houston drew in self-defense, he was acquitted of first-degree manslaughter charges. The Jennings clan never consummated a threat to avenge the shooting, but Houston had his share of close calls, with a notable one coming in Enid when he was shot by a would-be assassin. Luckily, the bullet lodged in a book of territorial statutes he happened to be carrying in his coat’s inside-chest pocket.

The private side of Temple Houston revealed a complex, immensely intelligent man, gifted and flawed, with assorted quirks, contradictions, and loyalties both fierce and tender. Throughout his marriage, he referred to his wife as “Valentine.” He walked with a slight stoop, head down, like a buffalo. His trademark attire in later years was a black Prince Albert coat, bell-flared pants over boots, a black cravat, a colorful vest, and a large white Stetson atop shoulder-length hair.

Perhaps because of his frequent solitary rides between courthouses, local cowboys gave him the nickname “Lone Wolf of the Canadian.” He seldom stayed in hotels, preferring to sleep under the stars in cow camps, and carried a small bottle of Tabasco sauce in his pocket to flavor his food. A voracious reader, one of his first stops in a town was its bookstalls. He was an authority on Napoleon and Aaron Burr and a collector of Native American and frontier artifacts. In later years, he befriended many Plains Indians, often allowing them to camp in his yard when passing through.

Houston adopted his wife’s Catholic faith and helped organize Woodward’s first Catholic Church. Three of his seven children died in infancy. He was a doting husband and father, never used corporal punishment on any of his youngsters, and once shot a man for spitting on his son.

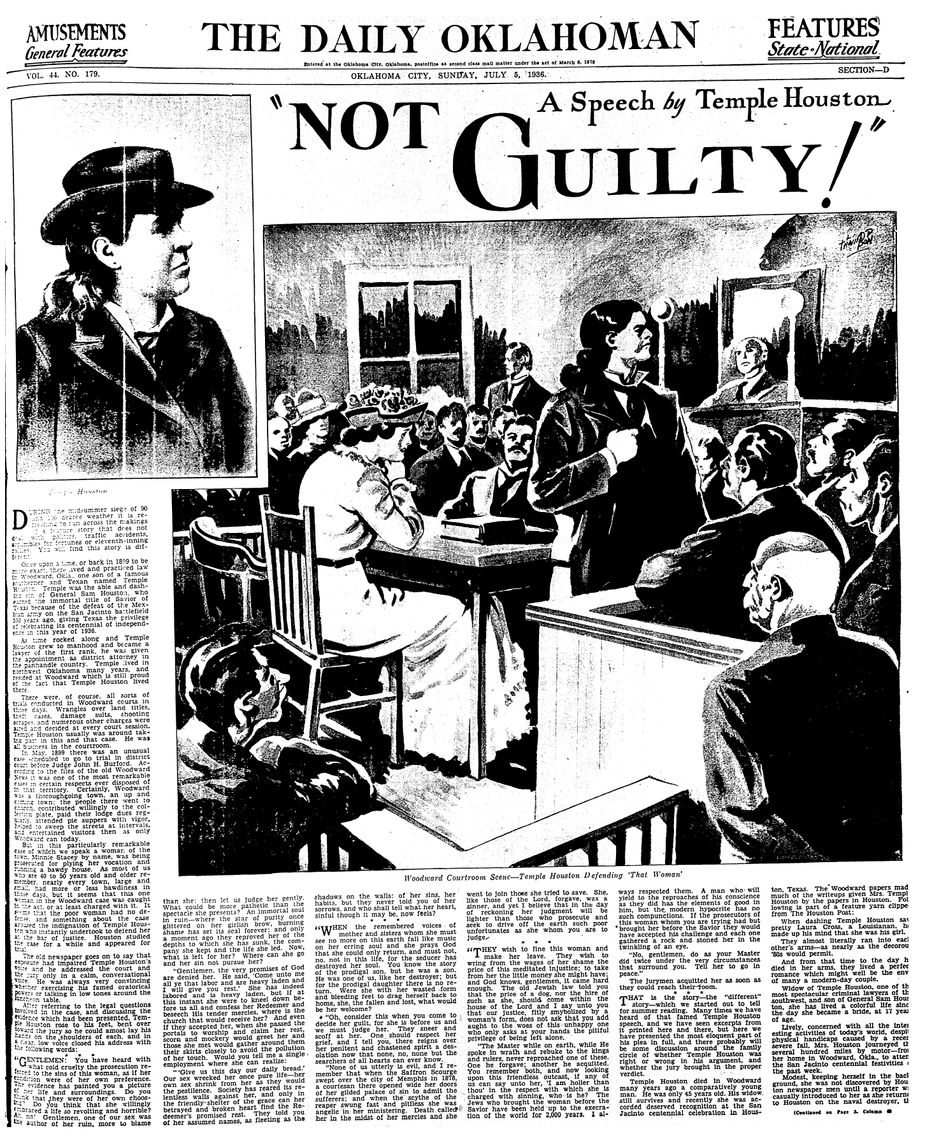

But it was a courtroom episode variously known as the “Soiled Dove Plea” and the “Plea for the Fallen Woman” that secured Houston’s place in territorial history. In 1899, Minnie Stacey was tried for prostitution. Unable to afford counsel, she was before the judge when Houston, there on another case, overheard her plight and volunteered his legal services, saying, “Your honor, I’ll defend the lady if she’ll allow me.”

A Daily Oklahoman story about the Soiled Dove Plea. Photo courtesy The Oklahoman.

He met with the accused for ten minutes before addressing the court on her behalf. His unrehearsed closing argument, once on display at the Library of Congress, was called “one of the finest examples of American oratory ever uttered.” Houston told the all-male jury:

Our own sex was the author of her ruin.... Where the star of purity once glittered on her girlish brow, burning shame has set its seal, and forever!...Now what else is left her? Where can she go and her sin not pursue her? Gentlemen, the very promises of God are denied her. He said, ‘Come unto me all ye that labor and are heavy laden and I will give you rest’....Society has reared its relentless walls against her, and only in the friendly shelter of the grave can her betrayed and broken heart ever find the Redeemer’s promised rest....There reigns over her penitent and chastened spirit of desolation now that none...but the Searcher of all hearts can ever know.

Alluding to opposing prosecutors across the room who would have “gathered a rock and stoned her,” he then challenged the jurors, “If any of us can say unto her, ‘I am holier than thou’...who is he?....No gentlemen, do as your Master did twice under the same circumstances that surround you. Tell her to go in peace.”

With scarcely a dry eye in the room, the jury unanimously acquitted the woman after a few minutes’ deliberation. The trial and Houston’s oral arguments were reported to much acclaim, even outside Oklahoma Territory. Minnie Stacey, the story goes, quit prostitution and moved to Canadian, Texas, where she supported herself taking in washing, joined the Methodist Church, became a devout Christian, and died there in the 1930s.

For weeks following the trial, the court stenographer was flooded with requests for copies of the speech, hailed by newspapers as “the most remarkable, the most spellbinding, heart-rending tear-jerker ever to come from the mouth of man.”

A contemporary, El Reno attorney R.B. Forrest, said of Houston, “He could touch a heart of stone in painting its sorrows. He seemed to feel the agonies of others and portrayed them with electric power.”

One of the great tragedies of his life, and one that probably shortened it, was his self-confessed “intemperate use of strong drink.” For years, he suffered from erysipelas—also known as St. Anthony’s fire—an acute, lymphatic-spread bacterial infection. In an era before safe and effective antibiotics and painkillers, alcohol provided the most effective relief.

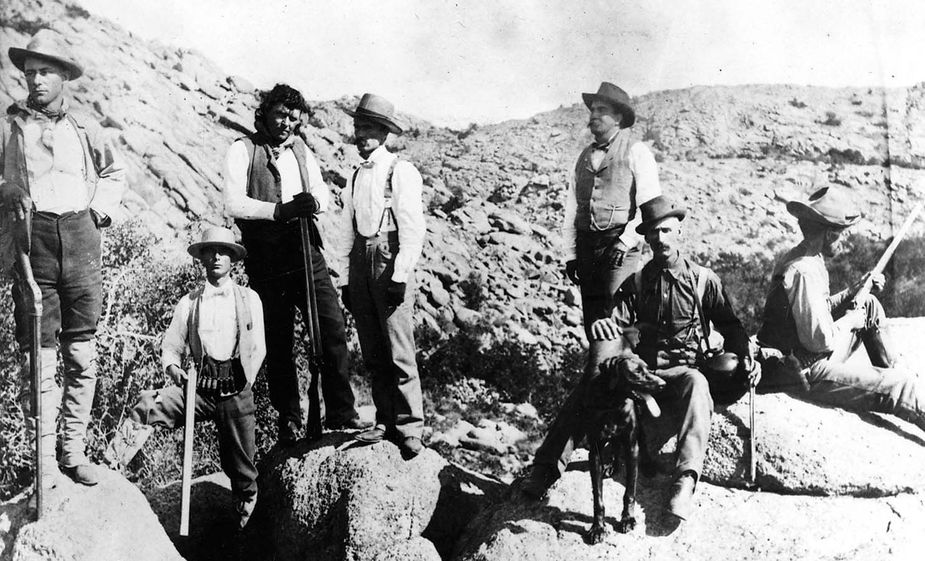

When he wasn’t in the courtroom, Temple Houston enjoyed the everyday activities of other men of his era. In this photo, Houston, third from left, with a hunting party in Nebraska. Photo courtesy Western History Collections/OU.

In a 1938 interview, Judge C.W. Herod, an associate of Houston’s, said, “When he went into a saloon to drink, it was quite the custom of Temple Houston to insist that every man in the house drink at his expense regardless of the number. Notwithstanding his vast earnings, he died in abject poverty.”

As talk of statehood spread, he was mentioned as a possibility for governor. Shortly before Oklahoma’s admission as the forty-sixth state, however, Houston died of stroke and brain hemorrhage three days after his forty-fifth birthday. Flags flew at half-mast over the Oklahoma territories and in Texas. Although relatives in the Lone Star State sought to have his interment there, his wife Laura reaffirmed his wish to be buried in Woodward.

According to legend, at his funeral was a prairie flower garland. The sender? The “fallen woman,” Minnie Stacey.

The Plains Indians & Pioneers Museum in Woodward has a gallery containing a number of Temple Lea Houston’s personal possessions and dioramas of his parlor and office. 2009 Williams Avenue, (580) 256- 6136 or nwok-pipm.org/houston-room. Houston’s grave is in the central part of Woodward’s Elmwood Cemetery at 2755 Downs Avenue.