Man of the West

Published December 2023

By Megan Rossman | 12 min read

Editor's Note: Harold T. Holden died in December 2023. This story is a repost of a feature Megan Rossman wrote about him for Oklahoma Today's July/August 2017 issue.

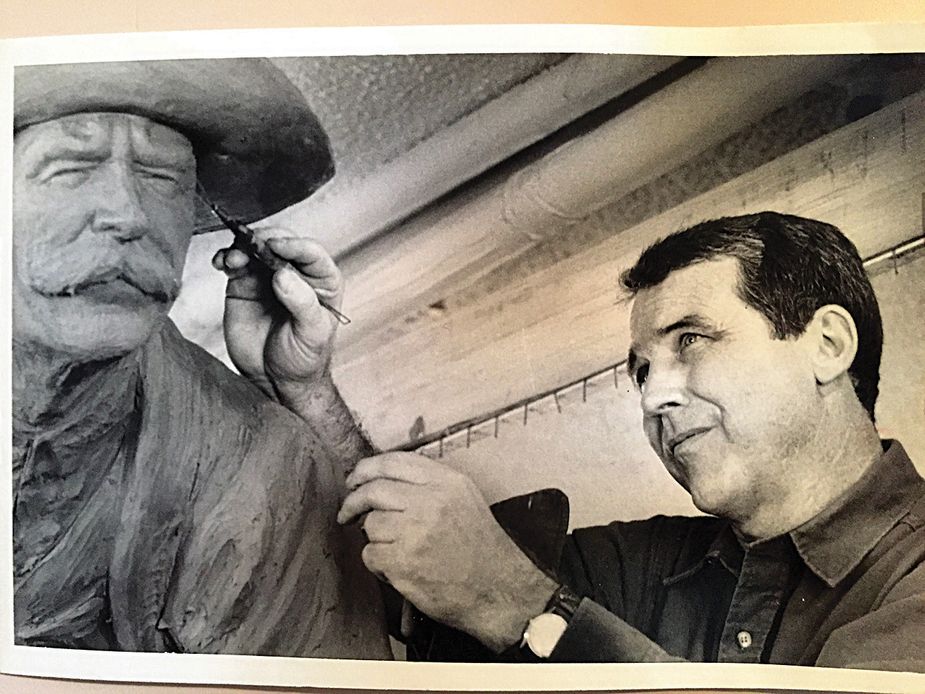

When it comes to his art, Harold T. Holden doesn’t do much expounding. During a two-hour conversation in his Enid home studio, he’ll discuss things like his four quarter horses or his influences, who include Charles Russell, Frederic Remington, and George Phippen. But his monolithic bronze sculptures occupying college campuses, museums, and other institutions around the region mostly are a segue to other topics. When asked what he’d like people to know about his work, he gives a little shrug.

“Eh, I’d probably say it’s authentic,” says Holden, who often is known simply as H. “I think you need to have some experience with your subject matter.”

Harold Holden at his home studio near Enid. Photo by Shane Bevel

Perhaps the reason Holden has little to say about his work is because it communicates just fine on its own.

Whether wrangling, riding, or roping, his bronze and clay figures are expressions of the cowboy grit for which the West is known. His horses—frozen in motion, muscles flexed, manes whipped by a prairie gale—are meticulous studies in equine anatomy drawn from a lifetime working with his subjects.

“If you’re going to sculpt horses and horsemen around here, you better know what you’re doing,” says Don Reeves, McCasland chair of cowboy culture at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, who’s known Holden since the late ’80s. “H is a horseman, and he likes to do art. He doesn’t blow smoke about anything.”

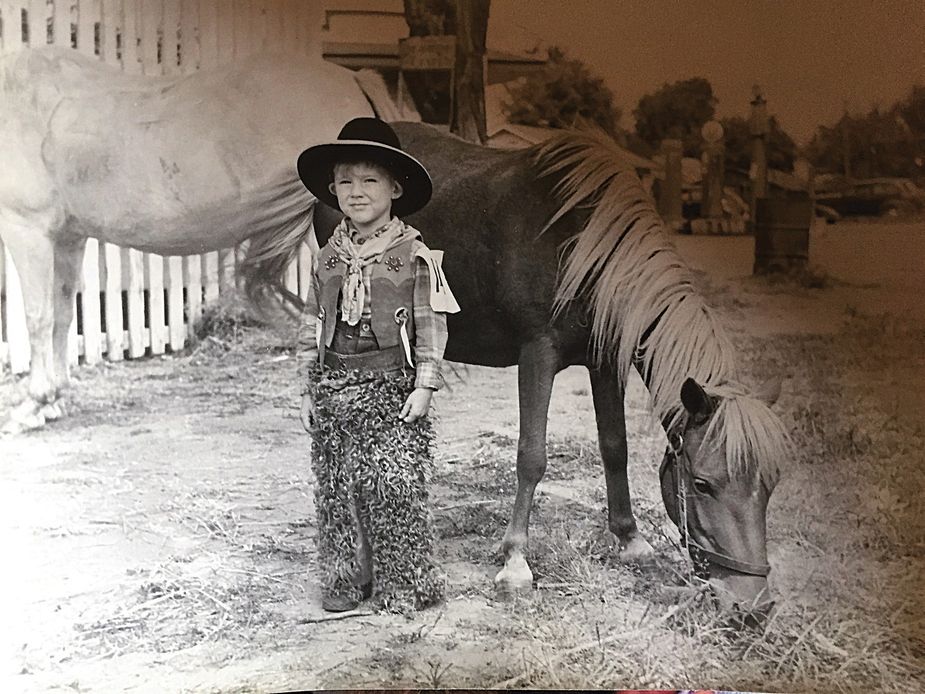

Holden at age five with his pony Daisey at the Strip Days Parade in Enid.

At the museum’s 2017 Western Heritage Awards in April, a gala roundup of cowboy culture’s who’s who, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners, a group that includes Jesse Chisholm, Sequoyah, Gene Autry, and more than 200 other influencers. Holden holds the distinction of being the first Oklahoma artist among them. As he took the podium, standing before the state’s largest annual assembly of tuxedos, cowboy hats, and handlebar moustaches, he spent several minutes thanking a list of people. Then, glancing at the event’s hefty Wrangler Award sitting next to him—a bronze figure of a cowboy atop a horse that he sculpted in 2011—he smiled.

“It seems a little strange to be receiving one of my own sculptures,” he said.

His trademark brevity, humility, and plainspoken wit paired with careful attention to realism have helped make Holden a beloved figure in the West’s art scene. When friends and family describe Holden and his work, genuine and authentic invariably are among the adjectives they deploy.

.jpg)

The monument *Headin’ to Market* was dedicated in 2000 in anticipation of the Oklahoma Centennial and is visible in Oklahoma City’s Stockyards City. Photo by Edna Mae Holden

An attorney by trade and an art agent by marriage, Holden’s wife Edna Mae can speak to his authenticity perhaps better than anyone. She has managed and promoted her husband’s career for twenty-eight years, and her business acumen has allowed him to remain focused on art as his commercial success has grown. When there’s a question about Harold, the response often is the same: “Edna Mae will know.”

And she does.

“He’s the same guy every day,” she says. “He’s a humble man, and he’s the same whether you’re the president or fixing the sewer.”

Holden created *Boomer*, his first public monument, in 1987. Photo by Jim Nay

Holden’s reputation as an artist is as solid as his good nature. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum curator of special exhibits Susan Patterson organizes shows with a sales component like Prix de West, which Holden has been invited to participate in every year since 1995.

“His work stands up to any contemporary sculptor. He’s known not just regionally but around the country,” she says. “His work looks authentic, because it is authentic. He’s sculpting what he knows.”

Art does imitate life in Holden’s case. Born and raised in Enid, he lives just north of the city with Edna Mae, a few miles off the historic Chisholm Trail, and the pull of the West has been with him since the beginning. Though his grandfather and great-grandfather were successful inventors, his father was a horseman, instilling in him an appreciation and knowledge of horses from an early age. For years, he raised and ran quarter horses with a cowboy cousin in Oklahoma and nearby states. After graduating from the Texas Academy of Art in 1962, Holden worked in commercial arts, eventually becoming the art director at Horseman magazine.

Along with countless awards and recognitions, Holden can claim a 1993 U.S. postage stamp, more than a hundred sculptures, and twenty-two public art pieces. And while he’s best known for monuments and sculptures, he also has created an extensive catalogue of paintings, pastels, and charcoals over the course of his more than fifty-year career. But he started painting less when he began to build monuments, a costly and time-consuming endeavor that put his work on the map in Oklahoma and surrounding states.

The enormous task of making them goes hand-in-hand with their size. Years ago, Holden would begin the process with a pinch model—a two-by-three inch approximation of the final work—and then he’d make a larger piece, called a maquette, a rough draft made to scale. From there, he would construct the full-size frame of the monument with tubing and nails and build on it with clay to create the final piece. These days, he brings the maquettes to Synappsys Digital Services in Norman, which uses 3D technology to create a delicate foam rendering of the model. He paints multiple layers of clay over the foam before sculpting and carving it. After he’s created a full-scale piece, it’s typically cut into sections so it can be transported to the foundry, where it’s reassembled, molded, and cast. Whereas his smaller sculptures might take a couple of months to complete, between the firing, casting, and original construction, it can take more than a year to produce one of the large pieces.

Among his many monuments is Headin’ to Market, a cowboy roping a steer located at Exchange and Agnew avenues in Oklahoma City’s Stockyards City. Others are The Broncho, a bucking representation of the University of Central Oklahoma’s mascot; a lassoing Will Rogers at the Will Rogers World Airport in Oklahoma City; and We Will Remember, a kneeling cowboy at Oklahoma State University’s Gallagher-Iba Arena in Stillwater, created in honor of members of the university’s men’s basketball team and staff who died in a 2001 plane crash.

The piece perhaps nearest and dearest to Holden’s heart came by way of misfortune. Holden was diagnosed in 2007 with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis—a terminal disease that causes lung tissue to inexplicably stiffen and thicken—and he and his family spent three years hanging on to the hope that a donor would give him the new lung he needed. Just when it was starting to look like death was imminent, Holden got the call he’d been waiting for in July 2010. After a six-hour operation involving seven people at the Integris Nazih Zuhdi Transplant Institute in Oklahoma City, the artist had his second chance.

“I went to see him the next day after his surgery, and I expected him to still be out,” says Don Reeves. “When I came in, he sat up in bed and started talking. He was so thrilled to be alive. The nurses kept trying to keep him from getting out of bed. It was incredible.”

Harold Holden’s sculpture *Homesteaders* is on display at the Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center in Enid. Photo courtesy Oklahoma State University

In honor of the donor and the medical professionals who saved his life, Holden delivered a cast of Thank You, Lord—a cowboy figure, hat in hand, arms outstretched, head raised in prayer—to keep vigil near the hospital’s entrance.

Since then, Holden’s had a few more procedures, but nothing keeps him from his work for long. He remains in his garage studio sometimes until the wee hours of the morning, sitting among saddles and tack, transforming canvases into glowing prairie horizons and shaping clay into the figures that first spurred his imagination as a boy. In a half-century as a professional artist, Holden’s never strayed from the West.

“Years ago, we had a conversation, and I told him we could live anywhere in the world with the work he does,” says Edna Mae. “He loves Oklahoma, and it’s given him a tremendous career. This is where he wanted to be, and this is where we’ve been.”