Petticoat Terror of the Plains

Published March 2021

By Karlie Ybarra | 22 min read

Belle Starr Queen of the Outlaws. Art by Ashley Dawn

There was a time within the memory of men now living when this dread name struck terror to the hearts of the timid and caused brave men to buckle an extra holster about their loins,” wrote Captain Kit Dalton in his 1914 book Under the Black Flag.

By the time that book was published, the woman Dalton was referring to, Myra Maybelle Shirley—better known as Belle Starr—had been dead for a quarter century. Her life was long over, but her legend still was gaining momentum. Borrowing her cachet for his own overblown biographical account, Dalton went on about the “Fearless Indian Outlaw.”

A more accomplished musician never coaxed dumb ivory into melody; a more daring bandit never hit the train nor cut a throat for the love of vengeful lust. A more winning smile never illuminated the face of a Madonna; a more cruel human never walked the deck of a pirate ship. She dispensed charities with lavish hand of true philanthropy and robbed with the strong arm of a Captain Kidd. No human ever risked life and liberty in more perilous ways for friendship’s sake than did this phenomenally beautiful half savage, nor was the gate to a city of refuge ever opened wider for the distressed than were of the doors of her humble mountain home . . .

Almost every word was fiction, but Dalton was by no means alone in this sin. Just months after Starr departed her earthly vessel, New York writer Richard K. Fox published Bella Starr: The Bandit Queen or the Female Jesse James and sold thousands of copies. Considering Starr’s name was misspelled in the title, it’s no surprise that the book is full of errors. Leagues of articles, books, and movies followed, many of which used Bella as a primary source.

Starr is among the most recognized female figures in Western lore, but she might also be the least understood. So if she wasn’t a hellcat on a horse galloping across the plains while firing two six-shooters at trailing U.S. Marshals, who was she? Perhaps the one thing Dalton and the others got right was that Starr was a fascinating set of contradictions.

“I’ve never seen so much rubbish written about someone in my life,” says Michael Wallis, a Tulsa author whose Belle Starr biography is slated for release in summer 2021. “When I talk about the West, I say, ‘Forget about the movies and the pulp books and all of that. Just know this: There were some white hats, and there were some black hats, but the majority were gray. Myra Belle Shirley’s hat was gray—and a lighter gray than many other romanticized figures from the West.’”

Myra Maybelle Shirley was born near Carthage, Missouri, on February 5, 1848, to Eliza—née Elizabeth Hatfield of the famously feuding Hatfields—and John. While John made a comfortable living as the proprietor of the Carthage Hotel, Eliza took care of the couple’s five children. Myra and her siblings grew up with many advantages. She performed piano recitals to adoring audiences in the hotel lobby. John’s extensive library offered the curious young woman a chance to explore philosophy and history. And at the

Carthage Female Academy, Myra excelled in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, among other subjects.

Though generally well-liked, Myra was no wilting flower. Contrary to what was considered proper for females at the time, she yearned for more than the domestic arts.

“Two interests obsessed her: horses and the outdoors,” wrote historian Glenn Shirley in his 1952 book Belle Starr And Her Times. “A competent horse-woman, she spent much of her time roaming the hills with her brother Bud.”

Belle Starr was famous for carrying a pair of revolvers. She was buried with one, though it was stolen by grave robbers. It eventually was recovered and now is on display at the Three Rivers Museum in Muskogee.

Bud, a.k.a. John Allison M., was six years Myra’s senior, but he treated her more like a friend than a little sister. He even taught her how to shoot a pistol and a rifle.

Idyllic as her childhood seemed, it was marred by bloodshed and the specter of war. When Myra was six, Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This allowed states to decide whether to permit slavery within their own borders. Pro-slavery Americans—particularly those from neighboring Missouri—flocked to Kansas to vote, steal, and otherwise illegally influence the election.

After Fort Sumter was taken by Confederates on April 12, 1861, U.S. Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton ordered Missouri’s governor Claiborne Jackson to send troops for support. Instead, Jackson called for fifty thousand volunteers to defend the state, and minutemen militias in small towns like Carthage started drilling nightly. Rival governments formed. Later that year, more than two hundred soldiers were killed in a skirmish just north of Carthage.

As slave owners, John Shirley and his family supported the South. Myra’s beloved brother Bud soon joined the bushwhackers led by William Clarke Quantrill, a Confederate guerilla leader. In June 1863, a company of Union troops discovered Bud’s whereabouts. In his book Jasper County, Missouri, in the Civil War, author and publisher Ward L. Schrantz sets the scene.

“…The militia surrounded the house,” writes Schrantz. “Both men broke and ran. Shirley was shot as he leaped over the fence and fell dead on the other side.”

Bud’s death devastated the Shirleys. According to Schrantz, sixteen-year-old Myra loudly vowed revenge against those who had killed her brother. In some accounts, she even tried to shoot Union soldiers with Bud’s gun, only to discover they had removed the caps. Shortly thereafter, the family packed up their belongings and left for Scyene, Texas, ten miles southeast of Dallas.

In November 1866, Myra married a family friend named James “Jim” Reed. The couple returned to Missouri to live with his family, and in September 1868, their daughter Rosie Lee was born.

Glenn Shirley writes, “She idolized the child and referred to her as her pearl; thus Rosie Lee became known by her nickname.”

Myra’s happiness was short-lived, however. Later that year, Texas Rangers killed her brother Edwin Benton, whom the Dallas News described as a “noted horse-thief.” For the next few months, Myra stayed in Missouri as her new husband gambled in Fort Smith, illegally sold whiskey in Indian Territory, and caroused with notorious men.

It isn’t clear exactly what manner of mischief Jim got up to, but in 1869, he thought it expedient to abscond to California with Myra and baby Pearl. In 1871, Myra gave birth to a son, James Edwin—later known as Eddie. A month later, Jim was in trouble again, this time over a matter involving counterfeit currency. The family hopped a stagecoach back to Texas.

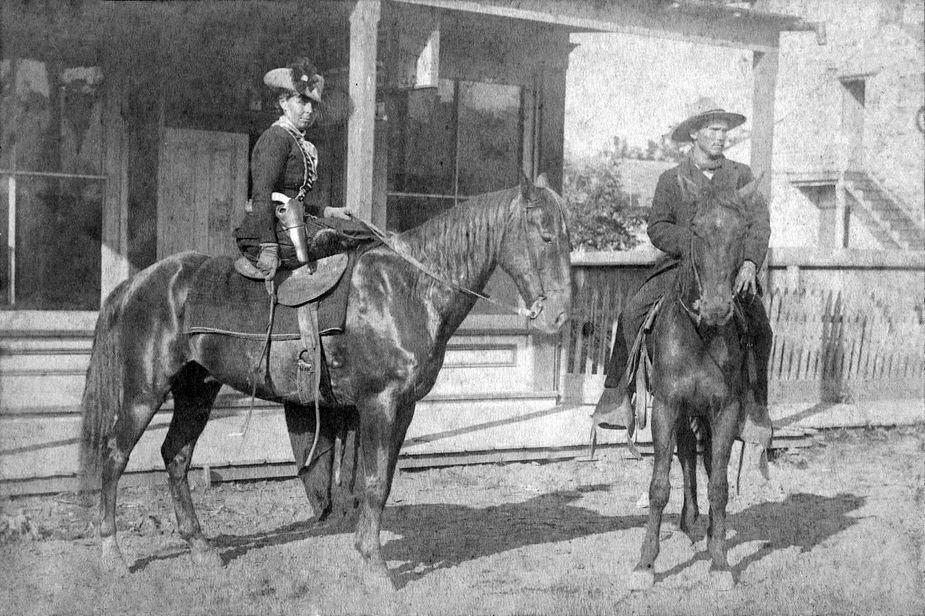

In February 1886, three masked men stole 40 dollars in cash, a pistol, and a horse from three homes near Cache. A witness identified one of the perpetrators as “a woman dressed as a man.” Belle was accused of being the gang leader, and she was brought to Fort Smith to answer to charges by B. Tyner Hughes—a deputy marshal working for the Choctaw Nation, seen here at right—in mid-May.

Once they returned, Jim once again swapped his straw farmer’s hat for a black one. In 1873, the Dallas Commercial reported that Jim, his brother Sol, and two other men robbed and murdered Dick Cravey. Now wanted for murder in two states, Jim left his wife and two children and fled to Indian Territory.

Around this time, many writers claim Myra participated in the theft of $30,000 in gold from a Creek man named Watt Grayson and his family. Fox even “quotes” the completely fictitious “Bandit Queen’s Diary:” “The old lady screamed with terror, but I placed the cold muzzle of my pistol against her brow, and that silenced her . . .”

Upon Myra’s return to Texas, biographer Burton Rascoe claims she moved into a Dallas hotel and leaned into a life of debauchery: drinking, gambling, shooting pistols into the air in the middle of town, and wearing outlandish costumes complete with a necklace of rattlesnake tails.

None of this can be verified. It doesn’t even make sense: A woman with two small children, a new farm, and a husband with a bounty on his head is unlikely to do anything to bring attention to herself. Furthermore, according to Glenn Shirley, Myra disapproved of the criminal life. In any case, Myra’s wayward husband got into enough trouble for the both of them.

“In February, 1874, he seduced a young girl named Rosa McComus and fled with her to San Antonio,” reported the Dallas Commercial.

Six months later, Jim earned his eternal reward when Indian Territory law enforcement agent Jno. Morris shot and killed him, for which he earned a bounty of $1,700.

There isn’t much reliable information about the next few years of Myra’s life, but that doesn’t stop writers from trying to fill in the gaps. Arson, bank robberies, hordes of lovers: It’s even rumored that the “Queen of Desperadoes” eloped with a Dallas deputy sheriff to get out of jail.

Whatever she was up to, Myra declared in an 1876 letter that she intended to sell her Texas farm. It’s around this time she supposedly married Bruce Younger, a relative of the famed Younger band of outlaws, though no marriage certificate ever has been found. Bella claims that Bruce and Myra spent some time together at Younger’s Bend in Indian Territory, but their relationship didn’t last. In June 1880, Myra married a handsome Cherokee named Sam Starr. She henceforth would be known as Belle Starr.

This replica of Belle Starr’s cabin is located near modern-day Porum. Photo by Lori Duckworth

Sam took an allotment near Eufaula. Nestled among the forested hills, the place was difficult to get to even in good weather. This locale, along with the Starrs’ less-than-law-abiding reputation, made Belle’s home a haven for some shady characters. Though she was happy to help a friend in need—even the likes of Jesse James—in an essay for the Fort Smith Elevator, she wrote of her desire to live a quiet life.

“On the Canadian River, far from society, I hoped to pass the remainder of my life in peace,” she wrote. “For a short time, I lived very happily in the society of my little girl and husband. But it soon became noised around that I was a woman of some notoriety from Texas, and from that time on my home and actions have been severely criticized.”

Of course, trouble eventually came calling. Belle first was charged with a crime in July 1882, when she and Sam were accused of stealing an eighty-dollar horse. The couple hid for eight weeks until they were captured by a deputy U.S. Marshal.

“Under the drapery of a pannier overskirt was a six-shooter; and concealed in the bosom of her dress were two derringer pistols,” recalled the marshal’s widow in a 1937 interview. “She fought like a tiger and threatened to kill the officers . . . and she meant it too.”

In February 1883, Sam and Belle were convicted and eventually sentenced to serve one year in a Detroit, Michigan, prison. Belle was released for good behavior after nine months, and she and Sam left prison at the same time. By the time she made it back to Younger’s Bend, her husband was on the run from the law for another robbery.

Frank West, a deputy U.S. Marshal working in Indian Territory, shot Sam, injuring the outlaw and killing his wife’s beloved horse Venus. As her husband was recovering, Belle was able to convince him to turn himself in. He went to Fort Smith and soon was out on bail, but justice apparently was too slow for West. On December 17, 1886, the Starrs were attending a party when the marshal showed up. He and Sam exchanged words and bullets, and neither man was left standing. Belle was a widow once more.

As a white woman, Belle had no claim on her Indian Territory property. This was quickly remedied, however, when she married another Cherokee, an adopted member of the Starr clan. Her third husband, Bill July, alias Jim July Starr, was twenty-four years old—fifteen years her junior.

Though she’d had disputes with her neighbors and family, Belle wanted nothing more than to live a peaceful and lawful existence. But once again, her contentment was fleeting. On Saturday, February 3, 1889, as she was making the journey home after ferrying across the Canadian River, a charge of buckshot blasted Belle off her horse.

“As she tried to lift herself from the mud, the assassin leapt the fence and fired off the other barrel of the shotgun,” Glenn Shirley writes. “This time a heavy charge of turkey shot struck her in the shoulder and the left side of the face.”

Her horse ran back towards the river, and a local boy followed the trail to find Belle still clinging to life. He retrieved Pearl, who arrived before her mother passed but was unable to coax from her the name of her killer. One of Belle’s tenant farmers with whom she had a dispute, Edgar Watson, was charged with the crime but was acquitted in a Fort Smith trial. The suspects, including Belle’s husband Jim July and her son Eddie, were many, and the mystery remains unsolved to this day.

No matter who put her there, Belle Starr was laid to rest near her home a few days later. Pearl designed her mother’s tombstone with a carving of a bell, a star, her favorite horse Venus, and a poem:

“Shed not for her the bitter tear, nor give the heart to vain regret; ‘tis but the casket that lies here, the gem that filled it sparkles yet.”

In 2010, Ron Hood, a Tulsa orthopedic surgeon, purchased the Younger’s Bend property near Lake Eufaula on which Belle Starr lived at the time of her death. Vandals had destroyed her gravestone, so Hood had it rebuilt from historic photos. He bought an 1850s cabin in Missouri, had it taken apart and moved to Younger’s Bend, and enlisted a Tulsa architect to recreate the Starrs’ home. Almost two years and thousands of dollars later, Hood had created a haven not for outlaws but for those who want deeper insight into Belle. Though the cabin typically isn’t open to the public, her grave bears coins, flowers, and other treasures left by travelers paying their respects.

In nearby Porum, the town holds an annual Belle Starr Day festival. Belle Starr Association president Sissy Swafford makes sure it’s an action-packed celebration of the town and the event’s namesake, including performances by the Indian Territory Pistoliers, a group of Wild West reenactors out of Fort Smith.

“One of their actors dresses up as Belle Starr, and they do shootouts in the street and carry people off to jail,” Swafford says.

Roger Bell, historian, author, and vice president of the Three Rivers Museum in Muskogee—where Belle’s sidesaddle and rifle are on display on loan from Hood—has led many tours from Muskogee to Younger’s Bend.

“People from all over the country go there. International people go there,” Bell says. “We took a group of people from England not too long ago.”

Starr was fatally shot while riding her horse near this spot along the Canadian River close to her home. Photo by Lori Duckworth

So why do people travel thousands of miles to visit the grave of a woman who died thirteen decades ago?

“She’s an anomaly,” says Muskogee author and historian Jonita Mullins. “She’s a woman in a mostly male-dominated career of criminal activity. And she came to fame at a time when the dime novel, which sensationalized these outlaws, was very popular. So it was kind of the perfect storm.”

Hood has an additional explanation for Starr’s enduring allure.

“Her story really is a tragedy,” he says. “She was raised affluent, and then her life was one of decline in major steps. Tragedies attract people.”

Was Myra Maybelle Shirley Starr a victim of tragic circumstances, a femme fatale disposing of men as quickly as bullets, or was she a figure too complex to characterize in just a few words? Whatever the case, Pearl knew what she was doing when she chose her mother’s epitaph. To this day, Belle Starr sparkles on the page and screen. In many hearts and minds, she forever will be riding off into the sunset, two pistols in her skirts and a gray hat perched atop her head.