Get to Know One of Oklahoma's Earliest Heroes

Published June 2019

By Jim Logan | 27 min read

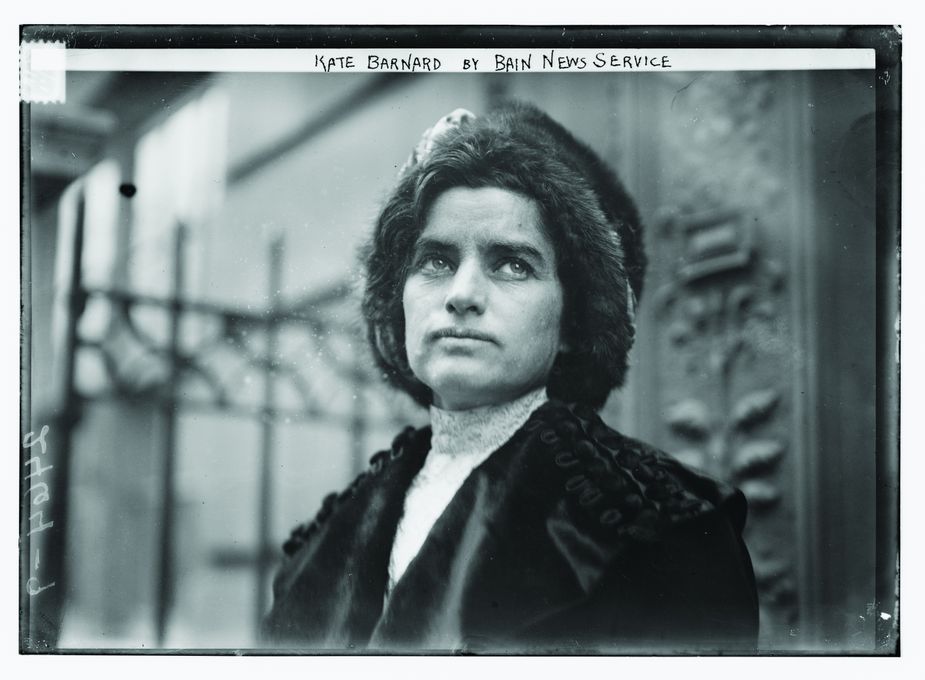

Kate Barnard was a leader in Oklahoma's early political landscape. A tireless advocate for the poor and disenfranchised, she helped shape the state's prison and child labor laws. Photo courtesy Museum of the Western Prairie

Near an old cedar in the northwest section of Oklahoma City’s Fairlawn Cemetery lies the grave—for half a century unmarked—of a near-forgotten individual whom historian Joseph Thoburn called “the most remarkable woman in Oklahoma.” From low beginnings and with little formal education, Catherine Ann “Kate” Barnard became a savior to the state’s children, orphans, poor, mentally challenged, hungry, infirm, and imprisoned.

Despite being five feet tall and just over ninety pounds, she struck fear into opposing politicians and was a driving force in the creation of Oklahoma’s groundbreaking constitution. With appeal that transcended party lines, she was the first woman in America elected to state public office—more than a decade before women had the right to vote in Oklahoma—and outpolled every candidate, including two governors with whom she shared a ballot.

In seven years in office, her impact was staggering. With a keen sense of public opinion, she magnetized journalists from coast to coast. A young Angie Debo saw her speak and later recalled that she “had power over an audience that seldom is equaled.” Barnard’s efforts led to passage of thirty laws, resulting in child labor reform, compulsory school attendance, a juvenile court and reformatory system for young offenders, orphanages, institutions for the mentally and physically disabled, prison reform, and modern, humane correctional facilities. She improved labor conditions for Oklahomans and brought national attention to orphaned Indian children defrauded of mineral and property rights by court-appointed guardians. Her work paved the way for Oklahoma women’s participation in social reform.

Opponents left early to avoid her in debate. Citizens and members of the media clamored for a glimpse of the woman who would write that she had witnessed life “from the homes of Fifth Avenue millionaires to the hovels of American slums, from receptions at the White House to gutter gatherings of homeless vagabonds and penniless tramps.”

When British Ambassador James Bryce visited Oklahoma and was asked about the state’s progressive new constitution, he said, “It is the finest document of human liberty written since the Declaration of Independence, and the credit for making it such is due, principally, to the activities of a single woman—Kate Barnard.”

Early in her political career, media reports often emphasized Kate Barnard's youthful demeanor and diminutive size, but she was 32 years old when she was elected Commissioner of the Oklahoma Department of Charities and Corrections. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Born in Nebraska to Irish-Catholic parents in 1875, Kate lost her mother before her second birthday. Her father, John P. Barnard, a wandering jack-of-all-trades, shuffled her among relatives, and her early life was marked by feelings of loneliness and desertion. She found solace in her Catholic faith and convictions about service. Unsuccessful in Oklahoma’s first land run, her father secured a claim in the second in 1891, near Newalla. He placed sixteen-year-old Kate on the property alone in a two-room shack for two years to “prove up” title while he worked in Oklahoma City. She joined him there at eighteen, where she studied at St. Joseph’s parochial school downtown, obtained her teacher’s certificate, and taught at St. Joseph’s and in rural schools until age twenty-seven. A year later, following a business course, she landed a secretarial position with the Territorial Legislature in Guthrie.

Among five hundred applicants, Barnard was chosen to become the territorial hostess, acting as an ambassador for the soon-to-be state of Oklahoma at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis. As one historian noted, “the slender, dark-haired woman of flashing eyes, smooth, high brow and olive skin . . . found it easy to communicate with the leaders of the exposition.” At a gathering of humanitarian organizations there, she met Chicago’s Hull House founder Jane Addams and other prominent names in social reform and saw her first big-city slums and their attendant crime, poverty, orphans, and children maimed in industrial accidents. From that day, her life was forever changed.

The young crusader returned to Oklahoma Territory in fall 1904 with what she felt was a mandate from God, determined to bear a torch for the less fortunate. Believing the answer to America’s poverty began with its children, she wrote opinion pieces for the Daily Oklahoman describing the misery in her west Reno neighborhood in Oklahoma City. From her home, she advertised for and received donations of more than ten thousand garments for children and the poor. Bringing women’s and ministerial groups together, she procured books, arranged medical treatment, organized the unemployed, and found jobs for hundreds of people. Her efforts led to a significant increase in the city’s manual labor wage.

As statehood approached in 1907, the woman newspapers now dubbed “Saint Kate” was suddenly riding the tide of public opinion. She became a key figure in the drafting of twenty-five demands for the new constitution, including compulsory education, mine inspections, child labor laws, eight-hour workdays for public employees, and a corporation commission to regulate business and industry.

Her persuasive appeal took the constitutional convention by storm. When the delegates approved her proposal for a department of charities and corrections, she was the natural choice to lead it, even though women were prohibited from holding public office. In an unprecedented move, she was allowed as a candidate for the position by proclamation.

Earnest and fresh, with style and presence, she drew huge crowds to her campaign speeches, delivered from corners, courthouse steps, and hay wagons. Her election card read: “Miss Kate Barnard, friend of the poor, Democratic candidate for State Commissioner of Charities, clothed and schooled 500 poor children, homed 2,000 of Oklahoma’s poor last year.”

To the surprise of few, Barnard won the election by a large margin.

Kate Barnard was well known in her native state of Oklahoma and beyond for her oratorical skills. Photo courtesy OPUBCO Communications Group

After taking office, the new commissioner was given a tiny room in the capitol’s attic alcove next to the men’s toilet. From there, Governor Charles Haskell and state politicians wrongly expected her to be quietly cooperative. One of her first moves was to slash her annual salary from $2,500 to $1,500.

“I cannot live on money that would rob little children of the necessities of life,” she explained.

Not long after taking office on November 16, 1907, she inspected Oklahoma City’s “pest house,” where victims of smallpox and other diseases were quarantined. When she finished, she filed a blistering report on its inadequacies. She also moved quickly to bring national authorities on child labor, juvenile delinquency, prison reform, and mental health to Oklahoma to educate the public and legislators. As part of her duties as commissioner, Barnard crisscrossed the state, inspecting jails, orphanages, and institutions for the deaf, blind, and mentally ill. In those years, it was commonplace for children to work in eastern Oklahoma mines, and within three years, Barnard had removed five hundred and put them in school.

At the time she took office, Oklahoma had no state penitentiary, instead paying Kansas to house nearly six hundred prisoners in its state penitentiary in Lansing. With rumors of mistreatment buzzing, in August 1908 she toured the facility posing as a visitor. After being shown only its best features, she confronted the warden, identified herself, and demanded to see everything. During the inspection, a boy grabbed her arm, pleading, “Make them show you the dungeon.”

When the warden denied its existence, she threatened legal action and was allowed to crawl through tunnels of the state-owned, prison-labor coal mine. There, she witnessed “the hole”—or dungeon—where an exhausted seventeen-year-old boy had been strung up in irons for failing to meet his quota of three carloads of coal a day. She also saw “the crib,” a coffin-like punishment box, and learned of inmates’ hands and feet being hogtied behind them.

When a prisoner yelled, “Girl, for God’s sake, see the water hole!” the warden terminated the inspection. After interviews with former prisoners, officials were able to confirm that the prison did indeed include a dark hole where prisoners were thrown and water pumped over them until they nearly drowned. A letter sneaked to her by a grateful inmate addressed her as, “our Kate . . . a rose in a desert waste.”

Her charges of cruel and unusual punishment, gross immorality, inadequate diet, harsh work schedules, and dangerous conditions reached newspapers, prompting public outcry and an investigation by a special commission appointed by the governor. The state upheld her twelve charges of inhumane treatment, and Oklahoma severed its prison contract with Kansas. In January 1909, amid falling snow, a thunderous roar went up from the inmates packed inside the train cars as the wheels began to turn for the journey home.

According to the biography One Woman’s Political Journey by Lynn Musslewhite and Suzanne Crawford, the trip was “a quiet one, broken only by the strains of an improvised song memorializing Kate Barnard.”

With the legislature making an appropriation to begin work on a new state penitentiary in McAlester, thankful prisoners gave—and kept—a promise of no escape to the new warden and built the new facility, which opened in April 1910, with their own hands.

The Kansas prison scandal rocked the nation. Over the next several years, Barnard addressed packed audiences and lunched with financiers and noblemen across America and Europe, discussing her views on prison reform. Arkansas and Arizona modeled their systems on her ideas, the New York Times did a series of articles on Barnard, and Arizona’s governor called her “the new Joan of Arc.” In an Oklahoma House session, an elderly representative, pointing up to her in the gallery, proclaimed, “Behold Kate, the good angel of Oklahoma!”

Barnard’s ideas on crime and prison reform were ahead of their time. She advocated separate juvenile and adult courts and cited poverty as a major crime cause, saying, “Man commits crime only when he is physically miserable or mentally unsound.” Along with the problem of sexual abuse when young offenders were housed with serious criminals, she believed the old system taught children “how to pick locks, blow safes, and murder men.” Prisons should and could, she felt, teach basic skills to transition inmates back into society.

Barnard’s anti-child labor speeches at Oklahoma A&M, the University of Oklahoma, and other colleges sparked thousands of student letters to legislators urging passage of a child-labor law, and her compulsory-education efforts saw an enrollment increase of more than 84,000 children in the state’s public schools. In 1910, she handily won re-election.

Kate Barnard was lonely and plagued by health issues. In a 2001 biography, Bob Burke and Glenda Carlile wrote that Barnard, yearning for company, often ate at the store where she bought sardines and bread for her lunch. She died at age 54. Photo courtesy Library of Congress

Kate Barnard was a private, driven woman, a product of her religious convictions and past. As one who felt called by God to her vocation, she could level harsh criticisms and rarely compromised. Though she advocated women’s support of charitable causes, she was frequently impatient with them. In an August 1909 letter, Barnard wrote, “While our women’s clubs have been . . . sipping pink tea and resoluting for two years, I went to work and secured a child labor law, the compulsory education law, and the juvenile court law.”

Her political battles made powerful enemies—none more so than the Speaker of the Oklahoma House of Representatives, and later governor, William “Alfalfa Bill” Murray, who viewed Barnard as “out of her place.” When Barnard challenged him to a public debate on union issues and a large crowd gathered in anticipation, he boarded a train and left town. She twice beat him in clashes on the House floor, once in a dispute over the role of her office and its appropriations, the other over child labor laws.

Though the first to coordinate large-scale charity efforts in Oklahoma, she felt them a poor substitute for a fair system, saying, “Charity is like pouring water into a sieve. It is the weakest of weapons with which to combat the problems of poverty or crime or disease. What people need is not charity but justice.”

Her efforts were hindered by factors out of her hands: poor funding and hiring control, division of authority, and male chauvinism. Opponents criticized her absences, some of which stemmed from her national demand as a speaker. Others involved travel to out-of-state medical facilities and recovery time. (Severe respiratory problems, depression, and incurable, disfiguring body blisters that mystified physicians from Denver to Johns Hopkins—recognized today as herpes simplex viral disorder—would haunt the last twenty years of her life.) Over time, as the state became more focused on economic opportunity and less upon compassion and communal responsibility, she found herself increasingly at odds with prevailing sentiment.

At age thirty-four, she lost her father, who, despite his early absence from her life, had strongly influenced her views on service, charity, and justice. (Her tribute on his gravestone reads, “Every good deed of my life I dedicate to him, and my one ambition is to live a life worthy of his name.”) The loss was a profound one from which she never fully recovered.

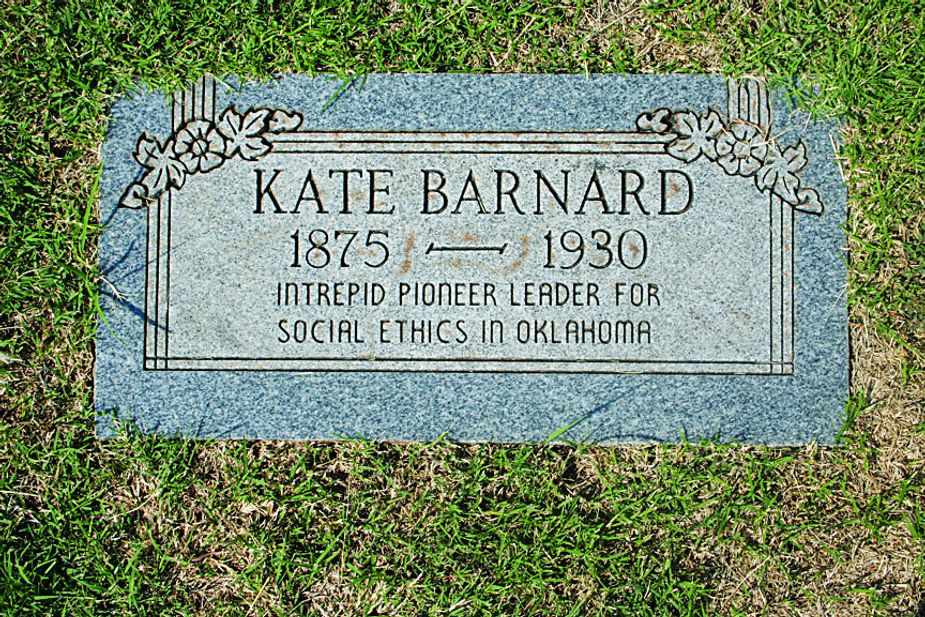

A small, unassuming stone at Fairlawn Cemetery in Oklahoma City was added to Kate Barnard's unmarked grave decades after her death. Photo by Megan Rossman

In 1910, Barnard took on an issue she labeled “the greatest blight upon Oklahoma.” It would wreck her health and mark the beginning of the end of her role as a state political force. The matter involved widespread abuse of orphaned Indian children by court-appointed guardians in which the children were fraudulently stripped of oil and gas holdings, timber, and farmlands through exorbitant fees, kidnappings, forgeries, and forced deed signings.

In what approached political suicide, Barnard and her special prosecutor, J.H. Stolper, intervened in 107 such cases across twenty-five counties in 1911, winning all and implicating politicians, judges, and corporations. Her whistle-blowing prompted a federal investigation by the United States Board of Indian Commissioners. Angry Oklahoma power brokers felt she was disgracing the state, threatening its sovereignty with federal involvement, and had to be stopped.

The state legislature launched its own, retaliatory investigation into her office, and members who were enemies of Barnard and Stolper’s efforts accused him of accepting bribes. Though unproven, the charges led to Stolper’s resignation. Barnard replaced him with a respected former judge, Ross Lockridge. The investigation could find no significant wrongdoing by Barnard but listed her absences and travel expenses as concerns.

When an attorney, presumably sent by members of the legislature who were not in favor of Barnard’s activities regarding the Indians, offered to take the place of her new prosecutor and promised to convince the legislature to back off, she refused. The legislature answered by attempting to eliminate her commission. Members were constitutionally prohibited from doing so, but in retaliation, they slashed her budget appropriations, effectively crippling her office.

Barnard took her reformer’s zeal national, in 1912 convincing the United States Congress to create a National Children’s Bureau (later to become the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare) to oversee matters pertaining to children’s welfare. She later wrote, “I have been compelled to see orphans robbed, starved, and burned for money. I have named the men and accused them and furnished the records and affidavits to convict them, but with no result.”

Her allegations of widespread criminal conspiracy to defraud Oklahoma Indians would eventually be substantiated. While her support waned at home, the influential Oklahoma literary digest Harlow’s Weekly, mindful of her popularity as a reform speaker in New York and neighboring states, called her “the most powerful single influence on public opinion in the East.”

But the stress of constant fighting with the Oklahoma legislature, along with chronic illness, took its toll. In a 1913 Kansas City Star interview with noted journalist Fred Barde, she confided: “I am sick and tired of it all. There is hardly a newspaper in Oklahoma sincere enough to befriend me. I have been forced to fight, inch by inch, for my very existence. I have made enemies . . . but I would not compromise with a single one of them.”

Barde wrote, “Commonly, this little woman . . . was capable of overcoming all obstacles with the fire of her zeal, unafraid and defiant. To see her in tears and despondency was something strange and new.”

A 1913 article in the New York Herald Tribune observed, “Looking at her, and listening to her with her tiny face and her ninety pounds, and her five feet of height, her big eyes and her earnest young voice, it is impossible not to think of her as a child . . . and then one remembers, with a sort of shock, the work that she has done.”

A member of the Board of Indian Commissioners, Warren K. Moorehead, traveled to Oklahoma to visit Barnard, whereupon he asked, “Where are all these big men of the West . . . and why are they not supporting this woman in her heroic fight?”

With state newspapers largely mute on the Indian issue in what Wilma Mankiller and Michael Wallis, in Mankiller: A Chief and Her People, termed “a conspiracy of silence,” Barnard spoke to cheering audiences across the country. In 1915, however, unable to raise money for her cause, exhausted, and disillusioned, she vacated her state office at the conclusion of her second term and focused much of her efforts on the Indian guardianship issue from the private office she opened in downtown Oklahoma City. With a heart condition now added to her skin and respiratory disorders and depression, she vacated her personal office the next year and shut the door on her public life forever.

The next ten years she spent unsuccessfully seeking medical cures across the country. Following stays in Hot Springs, Arkansas, and Denver to find relief from what Barnard called a “parasite,” she returned to Oklahoma City in 1925. By the following year, her mind clouded by pain, paranoia, and medications, the woman who once was the toast of the state had become a forgotten, fifth-floor recluse in Oklahoma City’s Egbert Hotel, located on Broadway Avenue on a site now occupied by the First National Center.

On a cold February Sunday in 1930, a hotel maid found Barnard dead of heart failure in her bathtub. State Capitol flags were flown at half-mast, and nearly 1,400 crowded into St. Joseph’s Catholic Church in downtown Oklahoma City for her funeral. When no relatives would claim responsibility, an unknown person stepped forward to handle funeral arrangements. She was buried beside her father at Fairlawn Cemetery. Seven former Oklahoma governors served as honorary pallbearers.

Appreciation for Barnard’s accomplishments has manifested slowly over the years and in modest ways. Her grave was unmarked for more than fifty years, until a small headstone was provided by a group of Oklahoma women in 1982. The inscription reads, “Kate Barnard, 1875-1930, intrepid pioneer leader for social ethics in Oklahoma.” An Oklahoma City women’s correctional center named for her is housed in a converted motel. Oklahoma sculptor Sandra Van Zandt’s statue in the State Capitol was erected in 2001, seventy-one years after her death.

Kate Barnard’s inspired vision for her new state and its utopian possibilities placed Oklahoma at the forefront of national social reform. In the end, however, she looked upon much of her life’s work as unfinished. An early belief in her calling and the American capacity for greatness and fairness was tempered over time by disillusionment with the realities of an imperfect system that took a huge personal toll. “Our Kate” was perhaps, to borrow a line from Willie Nelson, an “angel flying too close to the ground.”

As former Governor George Nigh stated in the foreword to Bob Burke and Glenda Carlile’s Kate Barnard, Oklahoma’s Good Angel, “We are better because of her.” Few Oklahomans have done so much for so many.

In 1998, the Oklahoma Commission on the Status of Women created the Kate Barnard Award to honor women in public service in Oklahoma. ok.gov/ocsw. Sandra Van Zandt’s sculpture of Kate Barnard is located on the first-floor East Gallery of the Oklahoma State Capitol at 2300 North Lincoln Boulevard in Oklahoma City. (405) 521-3356. The Oklahoma Territorial Museum in Guthrie offers two programs for student groups, “Kate Barnard in Person,” a living history lecture, and “Kate Barnard: In Her Own Words,” an interactive lecture, and she is featured in the museum’s Statehood and Bending the Rules exhibits. 406 East Oklahoma Avenue, (405) 282-1889 or okterritorialmuseum.org.