Stone Age

Published December 2024

By Natalie Mikles | 7 min read

Nothing about Willard Stone’s hardscrabble Oklahoma childhood seemed to point toward him becoming a celebrated artist. In fact, the odds were stacked against him. But when Stone died in 1985, he was known as one of the country’s preeminent contemporary Native American artists. Today, the Cherokee sculptor’s work is part of the collections at the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, the Five Civilized Tribes Museum in Muskogee, and the Cherokee Heritage Center in Tahlequah. He also has his own dedicated space, the Willard Stone Museum, in Locust Grove.

But before all that, he was the son of sharecroppers in Oktaha. His father died of Spanish flu in 1917, leaving his mother alone to farm the land with eighteen-month-old Willard and five other children. Shortly after, the family survived two murder attempts by the owner of the farm, who didn’t think the family could complete the harvest on their own. He hired two men to convince them to forfeit their share—or else. In one of those murder attempts, the Stones had gathered in the living room for warmth around a fire when a homemade bomb was thrown onto the roof of young Willard’s bedroom, where he slept nearly every night except this one.

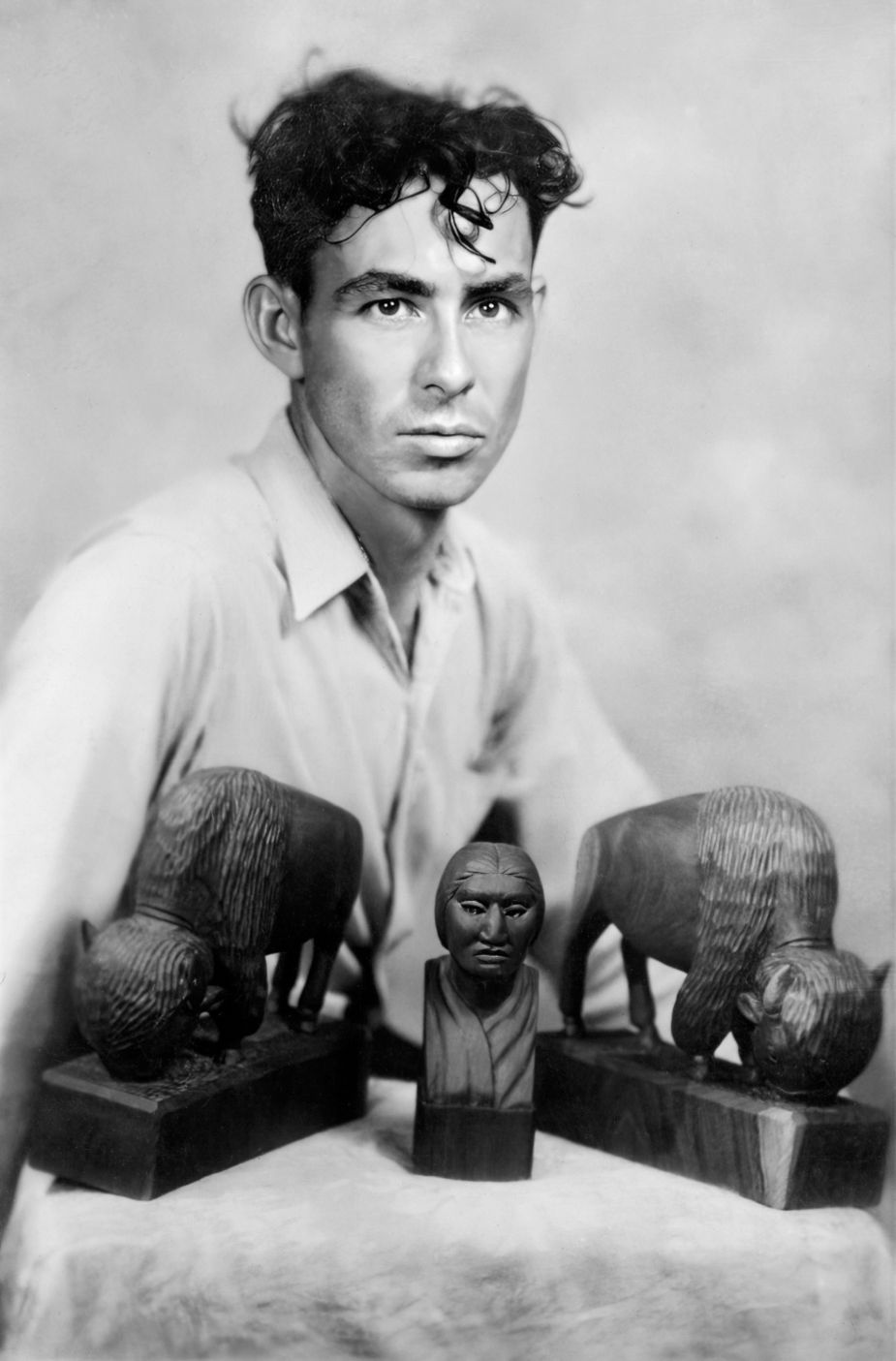

Willard Stone during his time at Bacone College. Photo courtesy Linda Stone Callery

When Stone was thirteen, he blew off three fingers on his right hand (his dominant hand) by unknowingly lighting a dynamite cap. As part of his rehabilitation process, he strengthened his hands by molding the red clay found outside his house. Very quickly, Stone and those around him realized he had a real gift: Out of the red dirt, he created sculptures that were unbelievably good for a teenager. One of the first admirers of his work was the mailman, for whom he would leave his red clay sculptures on the mailbox. The mailman was so impressed that he brought Grant Foreman, a prominent Oklahoma historian and member of the Oklahoma Hall of Fame, to meet sixteen-year-old Stone.

“He said, ‘I want you to come meet this young man. He’s lost his fingers, he’s quit school, but he has this gift,’” says Linda Stone Callery, one of Stone’s daughters.

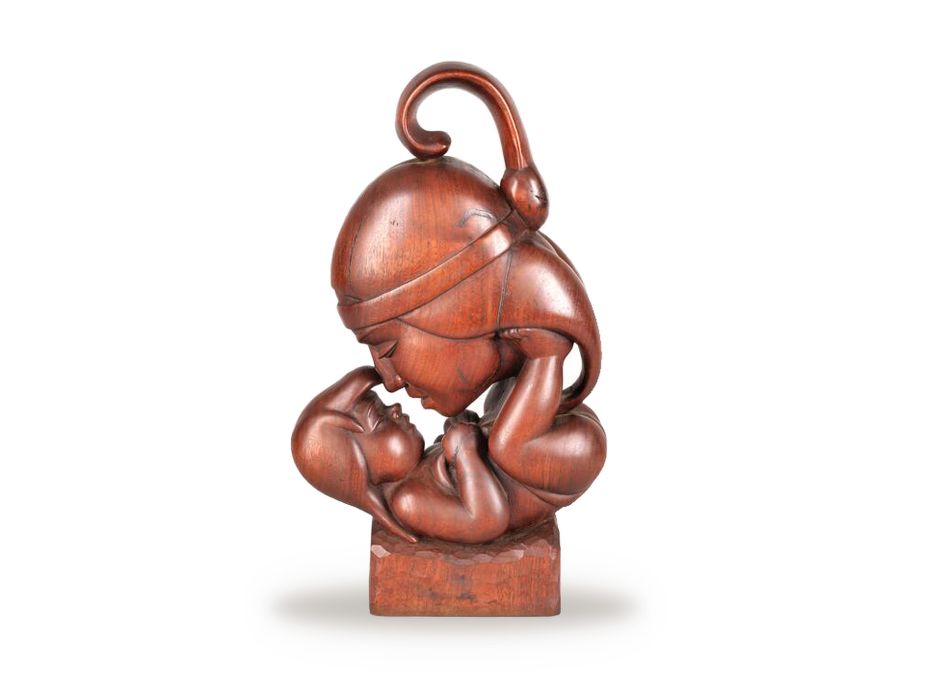

Turkey Feather Halo was Stone’s wife Sophie’s favorite piece. Photo courtesy Linda Stone Callery

That meeting changed the trajectory of Stone’s life. Foreman helped Stone get into Bacone College (formerly Bacone Indian School), where he honed his talent under artists Acee Blue Eagle and Woody Crumbo. Stone went on to work for Wiemann Ironworks (now Wiemann Metalcraft) in Tulsa and then spent three years as an artist-in-residence for Thomas Gilcrease at the Gilcrease Museum. Everything he sculpted at that time stayed in the museum’s collections.

After later working as a die maker at McDonnell Douglas, Stone decided to go out on his own, creating his signature wood sculptures from his home studio in Locust Grove. After he was inducted into the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1970, Stone had opportunities that would have taken him elsewhere, but he was proud of being born and raised in Oklahoma and never entertained those offers.

“He didn’t want to leave this hillside,” Linda says.

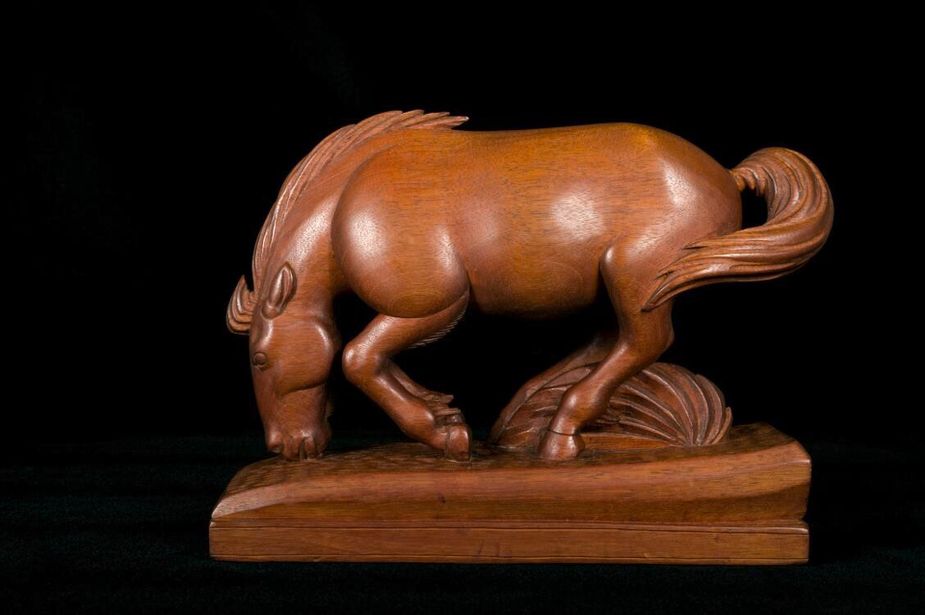

Willard Stone's sculpture The Mustang. Photo courtesy Linda Stone Callery

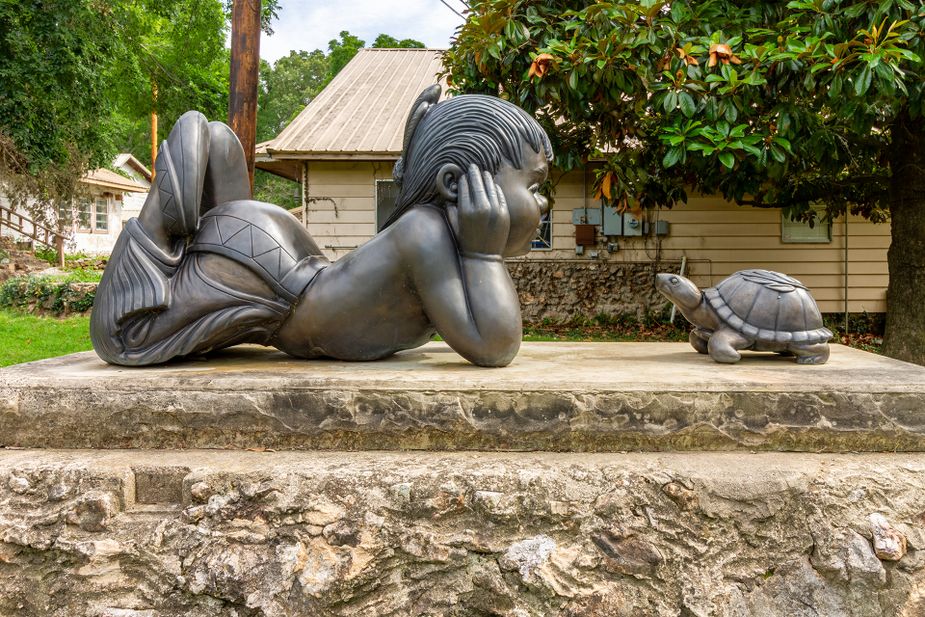

Willard Stone's sculpture Something to Believe In. Photo courtesy Linda Stone Callery

That hillside, where he raised his ten children and is buried today, also was the site of his art studio. It was his favorite place to be, surrounded by nature, carving his masterworks with nothing more than a pocketknife and a chisel. Fans knew where to find him and often stopped by the family home just east of downtown Locust Grove. Visitors became so frequent that Stone erected a museum on his property. His wife Sophie would open the door to the museum—which was nothing more than a metal building filled with treasures, including many of his Native American tribute pieces and a bust of Abraham Lincoln he made when he was only thirteen

It’s Linda’s dream to move the artwork, as well as his memorabilia and letters, to a building purchased for the new Willard Stone Museum in downtown Locust Grove. The two-phase project includes a goal of one million dollars for restoration of the bank building and another million for endowment. At times, it feels impossible to Linda, but she has her father’s determination. She’s often reminded of one of her dad’s favorite sayings: “Can’t never could do nothing.”

Willard Stone with two of his sculptures, Exodus (left) and Resurrection. Photo courtesy Linda Stone Gallery

One of Stone’s most admired works is of a Cherokee boy lying on his stomach, eye-to-eye with a turtle. The title of the piece, Something to Believe In, has become a sort of rallying cry and something for the new museum organizers to hang onto as they work toward the creation of a museum to honor Willard Stone.

In the meantime, Stone will be honored with the first Willard Stone Day in Locust Grove on November 2, which the family hopes to make an annual event. And what would Stone think of a day to celebrate him in the Oklahoma town he loved?

“I think he would be proud,” Linda says. “He would be pleased—and he deserves it.”

.png)