Take Us Back to Tulsa: The Tulsa Sound Part Two

Published August 2020

By Preston Jones | 23 min read

This is the second part of a two-part story on The Tulsa Sound. Read the first part here.

In the mid-1970s, Billboard magazine, long the music industry bible, seemed a bit besotted with Oklahoma musicians.

“John D. Loudermilk, the famed songwriter … once expressed a theory about vibrations and songs,” went one such piece published in November 1974. “Certain territories, he felt, were conducive to good music because of the experiences of the past; the inspirations for talent of today were the results of things which had occurred in history, and were being felt today…. Whether the theory is sound, is, of course, debatable, but the vibrations coming out of Oklahoma today, and in the recent past, continue to make it one of those geographical centers which … seem to produce an abundance of talent.”

Who could blame music writers for their bullishness? As the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, Oklahoma musicians—particularly those with Tulsa roots—were everywhere: Leon Russell, David Gates, the Gap Band, JJ Cale, and many more were fronting bands or lending essential support to other rock stars of the day.

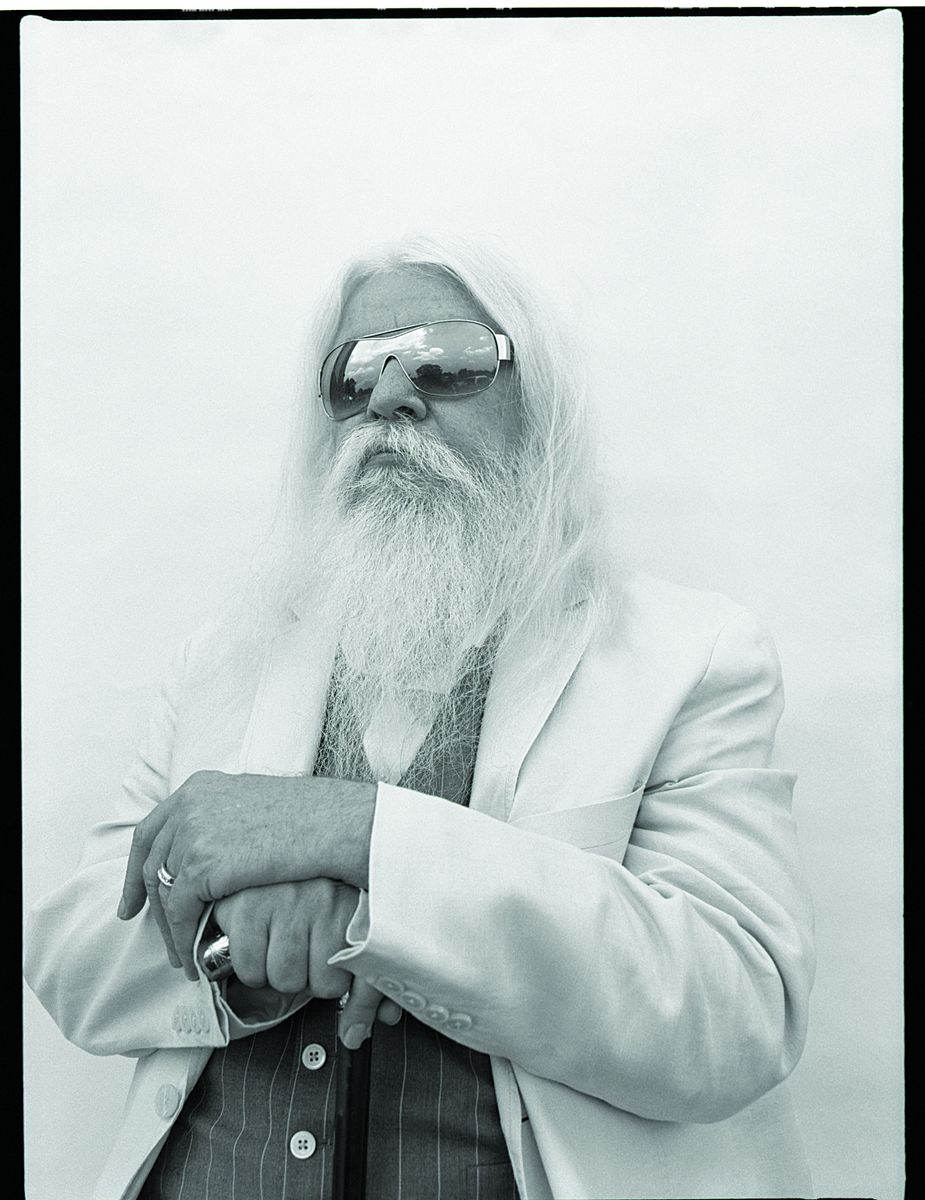

Leon Russell, photographed in early 2014, has become a reluctant figurehead for the musical movement known as the Tulsa Sound. Photo by David McClister

The Tulsa Sound, as it would come to be known, was fast becoming a key ingredient for artists from coast to coast—and beyond.

Starting Over in Miami

In the early 1970s, Jamie Oldaker and Dick Sims were playing regular gigs at clubs throughout Tulsa. When Oldaker wasn’t playing clubs, he was working for Leon Russell at Shelter Records’ Tulsa outpost, located at the Church Studio. At the time, bassist Carl Radle was a member of Derek and the Dominos, the short-lived blues-rock quintet founded by Eric Clapton. (Radle and Clapton initially met through—who else?—Leon Russell.)

Though the group would release one album, it was a classic—1970’s Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs. The band disintegrated in 1971, Clapton in the throes of heroin addiction and wracked with grief by the recent death of his friend Jimi Hendrix.

Carl Radle (from an August 1976 Guitar Player magazine interview): I split up Derek and the Dominos. I was the one who quit that. We were just a mismatch of personalities and lifestyles. So I quit and went back home and started playing with Leon again. Anytime I didn’t know what to do, I’d go and play with Leon.

Jamie Oldaker: I was playing the Observatory club in Tulsa. Carl walked in—he had just gotten back from LA—and said, “By the way, I got a call from a friend of mine: Eric Clapton.” I didn’t know who Eric Clapton was, really. I knew who Cream was, but I wasn’t familiar with Eric. Eric had just come off his heroin addiction. He called Carl and said, “I’ve been sitting here for the past year, playing to that cassette tape of those kids you sent me. I like that a lot; I’m getting ready to make a record in a few weeks down in Miami. Why don’t you bring those two kids with you?”

Eric Clapton, performing with Jamie Oldaker on drums. Photo courtesy Jamie Oldaker Photo Collection

Eric Clapton (from his 2007 autobiography, Clapton): When I arrived [in Miami], I was greeted by Carl, who then drove me from the airport to meet Jamie and Dick. They were very feisty young guys, bright and confident and not in the least impressed by me. They made me feel old, and I was only twenty-nine!

Before Oldaker could decamp for Florida, however, he had to inform his current boss—Russell—that he was planning to leave Shelter Records and the Church Studio to take the Clapton gig.

Oldaker: I went to talk to him on the second floor of his mansion [in Tulsa’s historic Maple Ridge neighborhood], a big ballroom with no furniture in it. This guy greeted me: “Leon’s upstairs; he’s expecting you.” At that time, Leon’s career was rolling pretty well. In the early ’70s, he was big stuff. The only piece of furniture that was in this big, huge, long room was this throne chair he’d bought—some antique thing in England, and he was sitting in it. Sunglasses on and top hat and twirling his beard. I was shaking, I was so scared. I approached him and told him the story. He looked at me and said, “Well, if it was for anyone else, I’d be upset. You have my blessing to go.” I thought, “Okay, cool.”

Once everyone arrived at Criteria Studios in Miami, the work, with legendary producer Tom Dowd, began on 461 Ocean Boulevard, Clapton’s sophomore solo effort. Released in July 1974, it became one of the defining rock albums of the decade, sold more than 500,000 copies in America, included a number-one single, “I Shot the Sheriff,” and landed at number one on the Billboard 200.

Clapton (from his autobiography): The idea was that we should play as a quartet, augmented in the studio by other artists, and I instinctively understood that the success of the record depended entirely on the kind of chemistry we developed. The first and most important task for me was to find a way to restore my playing ability in the company of proper musicians. We ended up finding a compromise in which they played minimally to my capabilities. This gave the music a certain charm, in that it was very basic.

Oldaker: We just played the way we played in Tulsa; we took those songs and played ’em the same way we would have at a nightclub in Tulsa. What came out came out.

Bob Seger. Photo courtesy David Teegarden Collection

Workin’ on some night moves

Clapton and Oldaker would record and tour together off and on through the ensuing decades, with the pair’s most recent collaboration—The Breeze, a tribute to the late JJ Cale—released in late July.

Clapton wasn’t the only bold-faced name Oldaker associated with in the 1970s. Prior to his stints with Clapton and Russell, the drummer kept time for Detroit rocker Bob Seger on the 1973 album Back in ’72. Seger also crossed paths with another Tulsa talent: David Teegarden, who first caught Seger’s attention via Teegarden & Van Winkle, his band with fellow Oklahoman Skip Knape.

Bob Seger (from a 2004 Detroit Free Press article): I’d always loved the way those guys played. I’d done a bunch of dates with them through the years. I played with them for about a year, all over the country.

David Teegarden: He couldn’t believe what he was hearing. Somehow he resonated with what we were doing. Seger and Mitch Ryder were the only two white guys in Detroit I thought had any soul. He started coming over to our house in Detroit, jamming with us and hanging out.

Teegarden and Seger, along with Knape and Michael Bruce, recorded 1972’s Smokin’ O.P.’s in two-and-a-half days at Leon Russell’s Paradise Studios on Grand Lake. Teegarden officially joined Seger’s Silver Bullet band in April 1977 and would continue to play with the rocker full-time until 1981.

Teegarden: We finished out the Night Moves tour, took a long break, and then started recording on the first album I was on with the Silver Bullet Band, [1978’s] Stranger in Town. That album did really well. What a fun ride.

In 1970, Leon Russell founded the label Shelter Records, which split its offices between Los Angeles and Tulsa, with British record producer Denny Cordell. In 1972, Russell moved back to Tulsa, where he installed three studios: one in his palatial Maple Ridge home; one at his lakefront home on Grand Lake; and the most impressive space, which would come to be known as the Church, at Third and Trenton.

Denny Cordell (from a 1973 interview with Billboard): We have the main studio in Tulsa, which is on Third Street and contained in a renovated old church. The ceiling is forty feet high, which makes for good acoustics. . . . We keep fourteen houses on that block for engineers, visiting artists, producers, publishing, and other visitors. . . . So if you come to Tulsa with us, you really get a home away from home. You just check in, and there’s very little pressure on you.

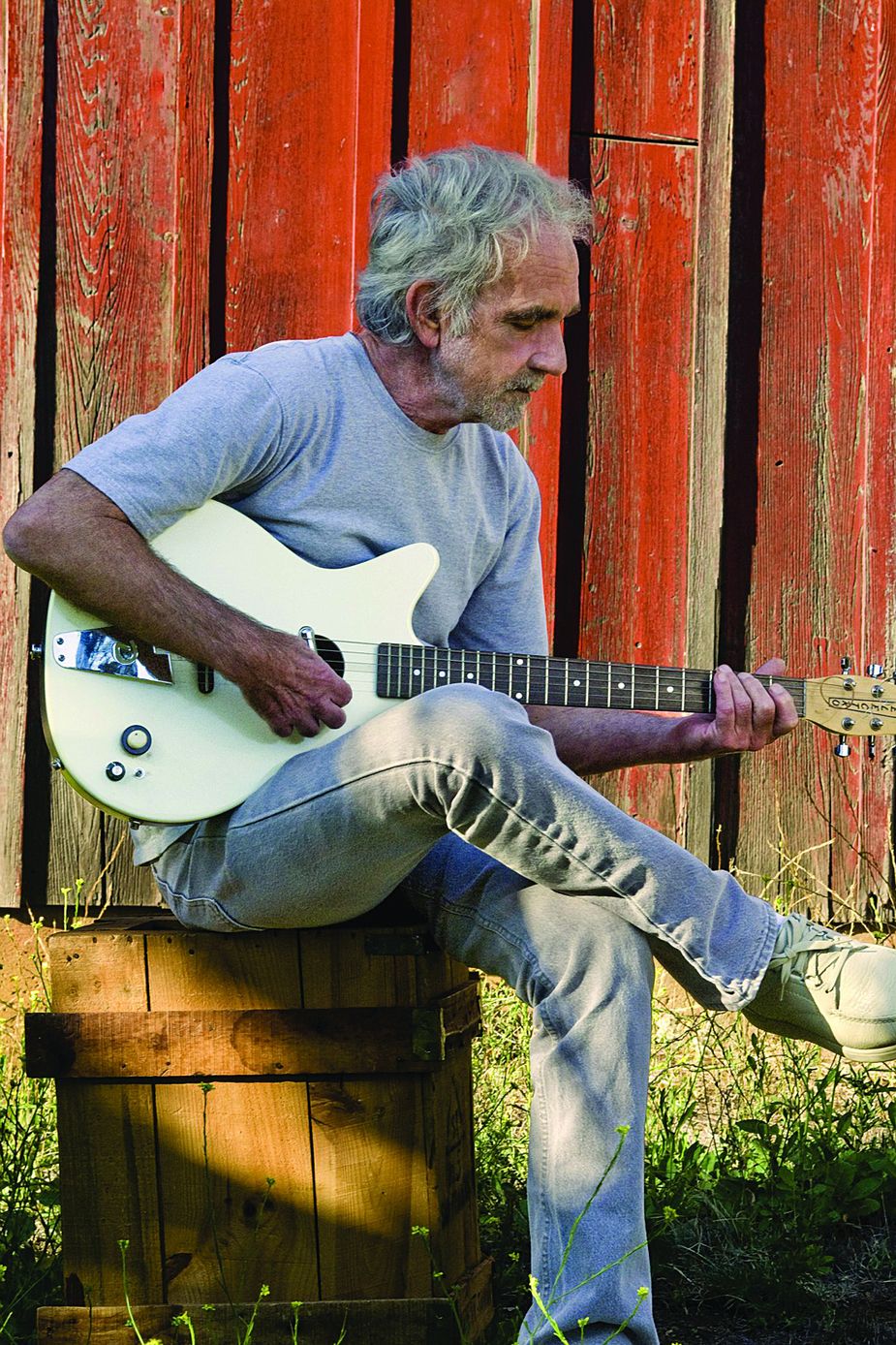

JJ Cale in a 2009 publicity photo for "Roll On". Photo by Jane Richey

A slew of great music proceeded to pour forth from the Church: JJ Cale, Dwight Twilley, the Gap Band, Freddie King, Phoebe Snow, Peter Tosh, and Tom Petty all recorded albums there. Russell, who split with Denny Cordell in 1976, would go on to form a new label, Paradise Records.

In 1977, Russell sold the studio to the Tulsa Indian Council on Drug Abuse, in whose hands it would remain for another decade.

In 1988, musician/producer Steve Ripley, who worked with Russell as an engineer at the Church in the 1970s, bought the studio and promptly brought in top-shelf talent—including Roy Clark, the Chainsaw Kittens, Ronnie Dunn, and Ripley’s band, the Tractors—to record in the space.

The Church Crowd: On September 19, 2014, Jeremy Charles photographed 24 men affiliated with the Tulsa Sound at the Church Studio. Front row: Jim Byfield, Roger Roden, Jimmy Markham, Chuck Blackwell, Tommy Tripplehorn, Tommy Crook, Larry Bell, Frank Brown, Ray D. Rowe, David Teegarden, Gary Gilmore, Danny Baker, Johnny Williams. Second row, on stairs: Don White, Chuck DeWalt, Bobby Taylor, John Hoff, Scott Musick, Jim Downing. Back row: Brian Haas, Billy Estes, Scott Ellison, Steve Pryor, Jamie Oldaker.

The Church

In 2005, Tulsa attorney Randy Miller purchased the building from Ripley after he happened to be driving past as Ripley was putting out a for-sale sign. In the ensuing decade, the studio has continued to be a bedrock component of Tulsa’s music scene, with Randy and his son Jacob serving less as owners and more as caretakers of a precious artistic legacy.

Jacob Miller: When Leon had it, they did wonderful things; then it went to Steve Ripley, and he did wonderful things. The history that’s come out of this place—it’s unbelievable. What my dad and I wanted to bring to the building was not so much our musical talent but our love for the building, our love for the arts.

Brian Horton, president of the nonprofit Horton Records label: We put out a compilation in 2010 and called it The New Tulsa Sound. Then we did a second compilation, The New Tulsa Sound Vol. 2: The Church Studio Sessions, where we had the old Church Studio for two weeks and brought all these bands in. We got to hang out and make this record, recorded all the songs there. I am so proud of that. You ask anybody involved, it’s probably the best two weeks of our lives.

The Church has been closed for much of 2014 as renovations begin on the 101-year-old building and the Millers prepare to expand the studio space. There’s also a chance the Millers will apply to have the building named to the National Register of Historic Places. Barring that, the family plans to establish a trust to ensure the Church endures for generations to come.

Miller: I just turned thirty. I started doing this when I turned twenty; it’s pretty wild. I plan on being sixty-five and still sitting on that porch and hanging out. If I get that far, I’m going to be a happy, happy old man.

As it was in the 1950s and 1960s, Tulsa once again is a hotbed of musical talent, full of artists unafraid of sitting in with each other and helping push one another to ever-greater heights. There’s a rich tradition of creative camaraderie in the Tulsa area, an unswerving constant through the years.

Now, Tulsa-bred musicians like JD McPherson, Annie Clark (who performs as St. Vincent), a few members of Broncho, and others are turning heads not only nationally but globally.

So, is there such a thing as the Tulsa Sound? And what’s more, does precisely describing the music—pinning down that specific sonic butterfly, to borrow writer John Wooley’s analogy from Another Hot Oklahoma Night: A Rock & Roll Story, matter more than its place of origin?

Jesse Aycock, Tulsa singer/songwriter: There’s always the debate about the Tulsa Sound and if it really is something. There is something about players in Tulsa—there’s a certain rhythm I feel is unique to here. Even my musician friends who have come to visit and gone out to see music say there’s some sort of character, and you can feel it.

Miller: There’s a community here that’s vast, and when Tulsa people say community, they mean it. They’re really one revolving band; it just depends on who’s singing that night. They are lifting each other up instead of trying to push each other down to get ahead.

Horton: It was a way to describe the music that was going on here at that time. The way the guy played the drums, and the bass player—just the pocket they created. It was a real laid-back feel and a really deep pocket.

Those who were active in the Tulsa music scene in its ’60s and ’70s heyday often dismiss the phrase “Tulsa Sound,” but none will deny that something—even if it can’t be precisely articulated— happened. They all heard it.

Teegarden: The players I grew up with—Cale and Leon and Carl Radle and people like Larry Bell—are the players I’m most comfortable with. Back then, I thought we were extra special, and we were. We had our own identity.

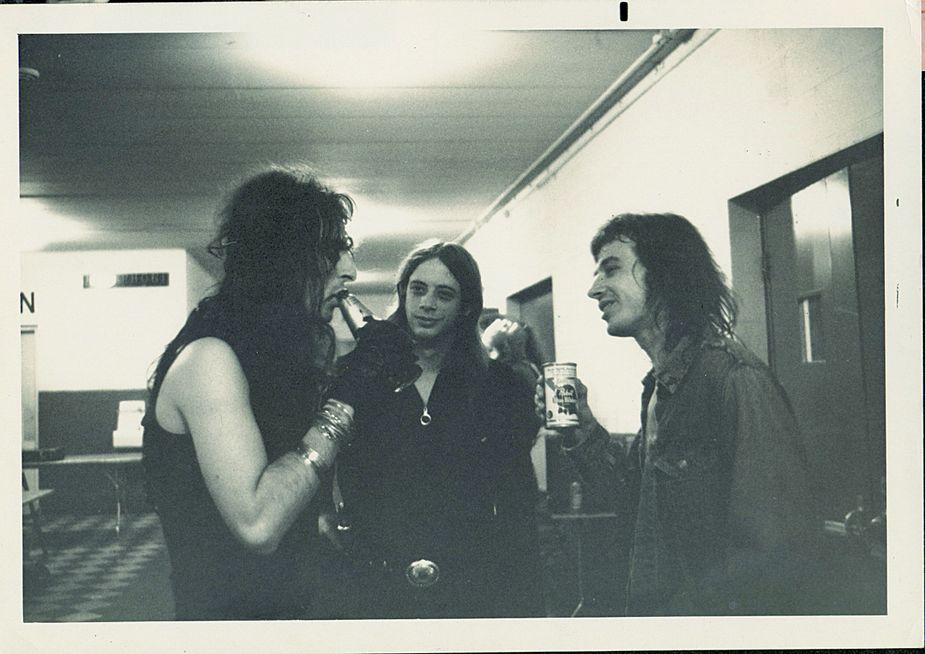

Alice Cooper, David Teegarden, and Skip Knape. Photo courtesy David Teegarden Collection

Jimmy Karstein: My take on it is, what the hell is the Tulsa Sound? I don’t think there is any such thing. If you take a Cale, a Leon, and a David Gates album, you tell me how they sound alike. They don’t. I used to collect 45 rpm records, and I was a big fan of Motown. I could take a stack of seventy-five of them, every one of them on Motown, and they would all have a similar sound. You could say, “That sounds like a Motown record,” whether it was Marvin Gaye or the Supremes or the Four Tops or the Temptations. Motown had a sound.

Cale (from a 2004 interview with Swampland.com): There isn’t no more a “Tulsa sound” than there is a “Cincinnati sound.” I mean, every town has got some musicians that have done pretty good. I think that was a marketing tool, so they could figure out how to market me. “He’s in the Tulsa sound.” Leon did good; David Gates of Bread did pretty good. But a lot of the sidemen musicians there are joint players, blues players, and so on.

Russell: I’ve had a great life; I can’t complain. I got to play on a Sam Cooke record. I played on a Johnny Mathis record. I’ve done a lot of stuff; I’ve played all over the world. I really can’t complain—it’s been great.

Karstein: I still work, but I turned seventy-one [in August]. Nobody said rock-and-roll was going to last forever. Well, rock-and-roll’s going to last forever, but the guys making it may not.

Jimmy Markham: If I knew [the Tulsa Sound] was going to be what it is today, I might’ve done some things differently [laughter]. I don’t know where the title came from, and we discuss this among the guys. The only thing that I can explain is it was a number of real good players who played together very well and were sympathetic toward each other.

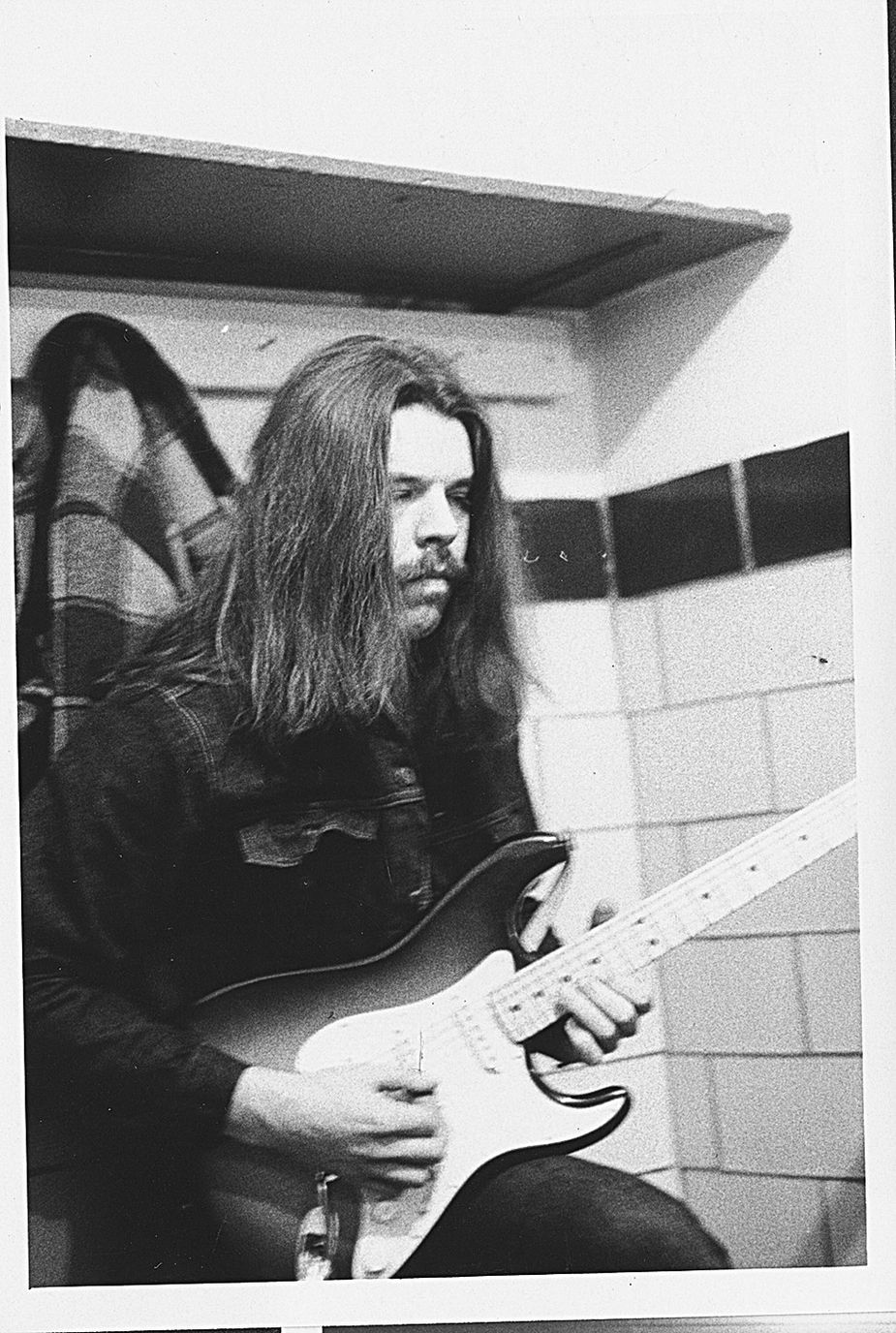

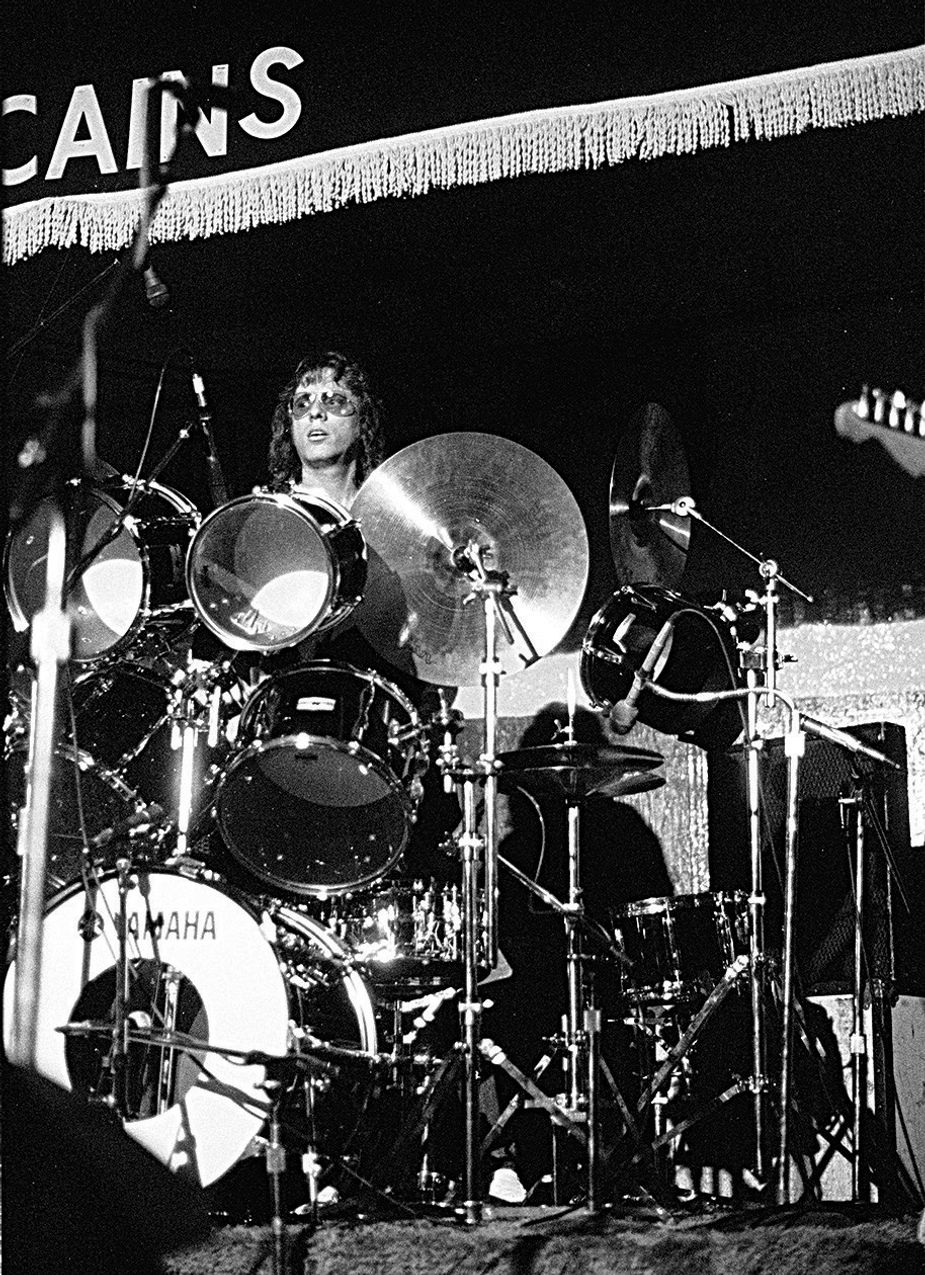

Jamie Oldaker in 1981. Photo by Richard Galbraith

Oldaker: People are aware of Tulsa music. It was a unique thing. People in the industry who know music will recognize that, but nobody really knows where it’s from. There are young kids who have said, “I grew up listening to records you played on, and I tried to learn how you did it.” It’s hard to copy. It may sound easy to some people, but if you sit down and try and do it, it’s not so easy. There’s a certain kind of groove, a certain kind of feel that goes along with all that stuff that’s interesting.

Karstein: Leon kicked the door in in California, and the rest of us slipstreamed in. That includes even Gates and Cale. They might have made it. There’s no way to go back and second-guess it. But Leon was definitely the point of the spear that was getting doors opened and people meeting people.

Russell: I’d love to take credit for being responsible for greatness. Unfortunately, it’s out of my hands. If there’s any greatness involved, it doesn’t have anything to do with me.

Winners Take Hall

The Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame keys in on the Tulsa Sound for its 2014 induction class.

The Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame announced in July that its class of 2014 inductees will include several key members of the Tulsa music scene. The late JJ Cale and Lowell Fulson will be inducted on November 1 at Cain’s Ballroom, as will Elvin Bishop, Jim Keltner, and Chuck Blackwell.

“This will be our first induction to focus on a genre and location. We are extremely excited to honor a number of Tulsa-based artists,” said Jim Blair, executive director of the Oklahoma Music Hall of Fame, in a statement.

.png)