The Long Drive Home

Published March 2020

By Robert Reid | 22 min read

Originally published in July/August 2017

I’m walking on someone’s unfenced land south of Bison with my new ladypal Kim and Tulsa photographer Shane Bevel, whom we just met. Our feet crunch through bleached prairie grass standing to our shins. We stop to ponder the slight indentions in the earth leading north toward distant fields of yellow canola.

Are these old wagon ruts? And is it even okay to be out here?

Honestly, we have no idea.

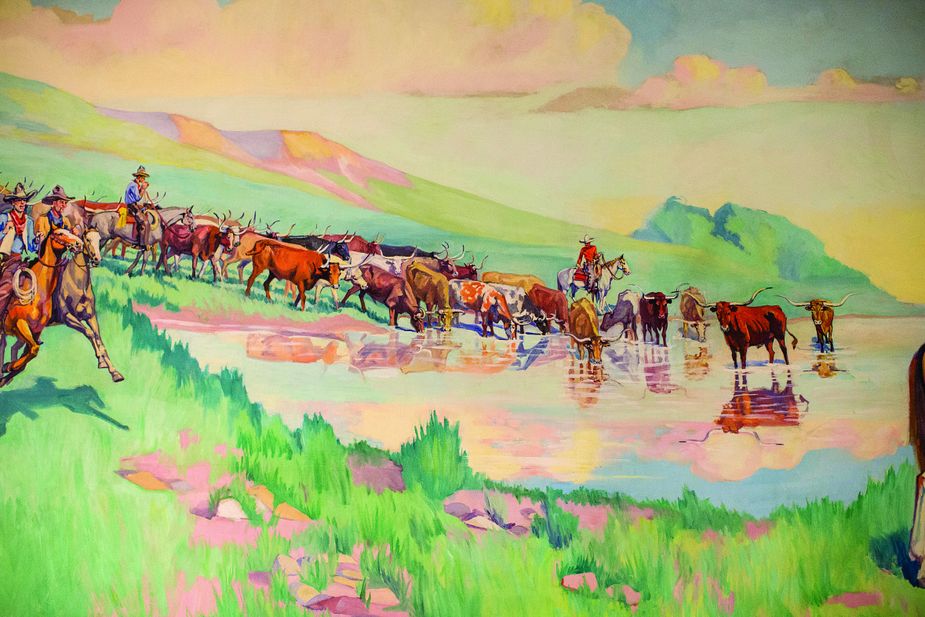

A Works Progress Administration mural in the Garfield County Courthouse in Enid depicts a day in the life of cowboys on the historic Chisholm Trail.

For all the talk about the Chisholm Trail, it can be a hard thing to find. This fabled cattle trail, which saw millions of longhorns march from Texas prairies to Kansas railroads over a couple of decades, turns 150 this year. And so we’re on a road trip to follow its path.

The trail itself is on and off—mostly off—U.S. Highway 81, which stripes the state west of I-35. A few brown historical markers point off the road—to where is often less clear—while interesting museums in Duncan and Kingfisher are easier to find. Beyond that, I’ve prepared by reading Wayne Gard’s 1954 book The Chisholm Trail, rewatching John Wayne in Red River, and clicking through ChisholmTrail150.org (now defunct), built for the trail’s anniversary events. But I’m discovering to really feel the trail’s history, and its ruts, can require some imagination and pluck.

“It’s more of a puzzle than a trail,” Kim reckons once we’re back in the car. That’s okay. We like a challenge. But privately, I can’t help but wonder if this is the best turf for Kim’s first real foray into the Sooner State. Our road trip following a disappeared cow trail begins in Texas, where we cross the Red River into Oklahoma via U.S. Highway 81.

“It seems flatter,” Kim deadpans.

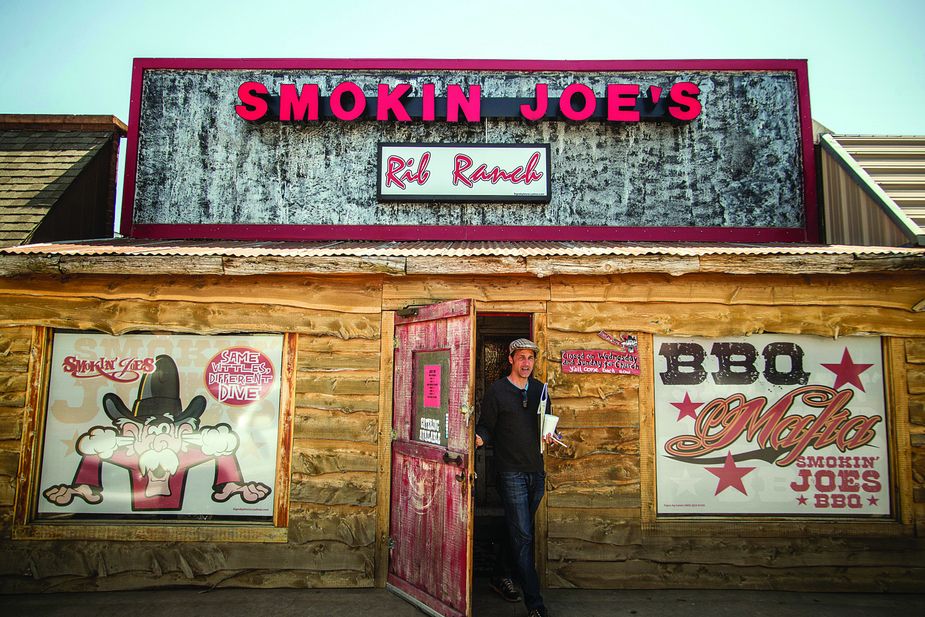

Reid fuels up on barbecue at Smokin’ Joe’s Rib Ranch in Rush Springs.

We pull first into the town of Terral, where three boys on BMX bikes lazily coast by Martin’s New & Used Shop along a wide, bare main drag. Continuing north, clumps of bright wildflowers—pink, orange, purple, and white—line the highway. The book Roadside History of Oklahoma by Francis L. and Roberta B. Fugate mentions a surviving Chisholm Trail landmark east of Addington, just to our north. There’s no sign, but I try a narrowing road. It dips through a tunnel of trees at a sunken gully then rises, revealing a reddish obelisk at a slight incline dubbed Monument Hill. Kim’s a Colorado girl, so this mound hardly qualifies as a mountain. But I long ago learned the deceptively big reward that slight contours in prairies and plains can give.

“Mountains are great, but they get in the way of a view,” I tease her.

So I’m not surprised when we reach the top of modest-looking Monument Hill to find arresting views as the sun begins to dip on the day. We get out some cold beers and sit and watch, listening to cows moo and coyotes yelp.

“Beautiful,” she says.

Oklahoma has gotten on the scoreboard.

Doug Davis of Hitchcock shows off a replica of Theodore Roosevelt’s pistol he had custom engraved.

Cowboys leading herds of as many as 10,000 longhorn on the Chisholm Trail rarely had carefree moments like these. When they did, they sang. Songs like the infectious “a-tie yie youpy youpy yay” chorus of “The Old Chisholm Trail” had endless verses, with new ones added regularly. Sometimes, they came at the expense of cattle barons back in Texas. These were small victories, considering cowhands—usually in their teens—made $10 to $30 a month, while ranchers built ranches the size of Rhode Island and netted fortunes from one of history’s biggest animal migrations.

All this, though, is why I found it so fitting to happen upon the Cowboy Opry in Comanche. Up front, it’s a guitar shop—pronounced “gee-tar” here without affectation—but a stage in the converted garage in back looks like a Hee Haw set with faux chuckwagons and a cardboard Roy Rogers cutout. The kitchen, fronted by a wall of mounted guitars, serves dinner before the Thursday night country, gospel, and bluegrass open mic. The guy behind it, Allen Wooten, is a six-foot-three former oil field worker who’s been into music since his parents gifted him what he calls “a Ward’s Kay guitar.”

“Music doesn’t pay as well as oil,” he says, slouching over the counter. “But it’s more fun.”

On the Chisholm Trail is a life-size, 34-foot long sculpture by Paul Moore that sits outside the Chisholm Trail Heritage Center in Duncan.

Besides inspiring music, the Chisholm Trail saved Texas. After the Civil War, Texas had few jobs and no railroads, but it did have millions of stray longhorns. The Northeast was in need of leather and tallow, and cattle would go for ten times what they would on the Plains. Missouri didn’t want them, because they were a home for ticks carrying fevers that killed their less hardy cows. So in 1867, Joseph G. McCoy, an Illinois businessman, made a deal with the Abilene, Kansas train station and built cattle pens to load longhorns for St. Louis, Chicago, and beyond. Then, cowboy drovers—patterned after Mexican vaqueros—walked them there. It could take three months one way. They came by way of a network of old trails Delaware scout Black Beaver had blazed in 1861, when he guided federal forces to Kansas in order to escape Confederate troops. Cherokee/Scottish scout Jesse Chisholm, whose name gradually found its way onto the trail after his death, led trade wagons along the same route.

The Chisholm Trail was never a casual stroll across Indian Territory, however, with constant danger of stampedes, drownings at rivers, and Native Americans demanding tolls—usually just a few head, though sometimes a scalp. The trail ran for a couple decades, until new railroads and barbed wire put an end to the cattle-drive days for good.

And this is where the cowboy legend was born.

Longhorn cattle at the Davis ranch in Hitchcock.

A good place to dive into that legend is Duncan’s Chisholm Trail Heritage Center. Best is its eighteen-minute video produced in Oklahoma that uses sensory immersion to show visitors what the trail was like.

Afterward, we make a quick hunt for wagon ruts east of town then detour on a patchwork of country roads northwest to Cyril. Filling a block, the Sia: Comanche Eagle Center is an impressive sanctuary for Comanche artifacts and a breeding center for eagles. Sia—the name is Comanche for feather—provides eagle feathers for use in Native American ceremonies nationally.

Founder and executive director Bill Voelker wears a “Comanche: Lord of the Plains” jacket, has his graying hair pulled into a ponytail, and leads tours of the center by appointment. He shows us historic photos and a glass case of Comanche lances decked in feathers and beads then leads us to the back garden to meet a golden eagle named Yahpahcony, or cricket, who only understands the Comanche language.

Bill tells me most Comanches sat out the Chisholm Trail, but some Texas ranchers employed “Comanche cowboys” to see their cattle safely to Kansas.

Reid and ladypal Kim step back in time and into throwback Western duds at the Davis family’s ranch in Hitchcock.

“Being a cowboy was one of the only ways we could have greater access to the world,” he says.

During the trail days, Indian Territory was merely the middle of the road. Unlike Texas or Kansas, it had only a handful of stores and essentially no towns. One exception was Silver City, a village north of present-day Tuttle.

All that’s left of Silver City today is the town cemetery. I park in a gravel lot and step into the hot afternoon sun. The first tombstone I happen upon is for Edwin G. Campbell, who died in 1881 at age eleven. The world through which the Chisholm Trail traveled was kind to few.

Afterward, we take a series of dust-kicking roads east to where wide plowed fields of churned-up dirt are backed by a wee line of trees edging the out-of-sight Canadian River. We flag someone down who tells us this is Braum’s farmland. A clerk at a Chickasha Braum’s later confirms that, “Yep, that’s where all this stuff comes from.” We ride to a dead end then walk a few hundred yards to reach the brown water lazily flowing east. This is roughly the location of the old crossing.

The Chisholm Trail Heritage Center in Duncan features a variety of interactive exhibits along with works by renowned painters like Frederic Remington, George Catlin, Charles Russell, and Allan Houser.

“I almost packed a canoe,” Shane glumly notes on a small sandy bank between thickets of seven-foot high reeds. “That way we could have paddled across.”

On the other side of the river, I see an identical sandy bank wedged between thickets of seven-foot high reeds. I nod.

The way back to Highway 81 soon bursts our 1860s bubble as we follow commuters into traffic-clogged suburbia. I’m surprised, in Yukon, when Kim casually notes how close Oklahoma City’s skyline is. By the time we reconnect with 81 at Okarche, we decide to get an early dinner of fried chicken at Oklahoma’s oldest bar, Eischen’s. While waiting for our order, I pen a twenty-first-century verse for “The Old Chisholm Trail:”

We follow the brown signs but can’t find no ruts.

Adventures are fun, but this is kicking our butts.

Come a-tie yie youpy, youpy yie, youpy yea

Come a-tie yie youpy, youpy yea.

The next morning in Enid, we stop by the Cherokee Strip Regional Heritage Center, which was hosting a Chisholm Trail exhibit that summer, then visit the courthouse to see the charming 1930s Works Progress Administration murals depicting Chisholm Trail drovers. But the reason we’re here is to meet the man who holds the Holy Grail of the Chisholm Trail.

Bob Klemme lives a ten-minute drive north of the center. We find him sitting in a new La-Z-Boy in front of a painting of a trail crossing. At ninety-one, he is possessed of a razor-sharp mind, recalling exact locations of the trail and the number of cattle that reached Abilene in, say, 1871 (600,000).

Bob Klemme of Enid has charted the Chisholm Trail on modern-day maps and placed many of the trail markers himself.

“You saw the post north of Dover?” he asks. “At the Boy Scout sign?”

In the mid 1980s, Klemme stumbled on an 1870s survey map of Indian Territory, plopped his thumb in the middle, and randomly opened it to where the trail passed through downtown Enid. So he started hunting it down.

“Seeing ruts,” he says, “made the hair on my neck stand up.”

At first, he marked points where the trail crosses barbed wire fences with beer cans but by 1990 began planting concrete markers. No one knows the trail in Oklahoma better than he does.

“I had fun every day—even if I hurt myself,” he says.

Once, he took a tumble in some freshly cut Johnson grass.

“Dang thing cut through my hand,” he says. “Oh, it bled like heck.”

The home of Marna and Doug Davis along the Chisholm Trail near Hitchcock has become an unofficial museum and destination for travelers.

By 1997, the state’s trail was stamped in full by more than four hundred markers. Then, he got to work on his self-published book, which is packed with maps based on 1870s survey originals and now is laid out before me. There are only twenty copies. We snap photos of some pages for ideas on where to go next, then drive back south on 81 to track down some wagon ruts. We find some a mile south of Bison, where Bob planted the first post in 1990. In Kingfisher, we take a look at the Chisholm Trail Museum. One exhibit highlights barbed wire’s role in the trail’s demise.

I do enjoy this hunt. But I’m still restless to meet the actual stars of the trail. Longhorns—a pure Spanish breed first introduced to the Southwest by Coronado in 1541—might be connected with Texas lore and sports teams, but their survival was only assured a century ago because of Oklahoma ranches and the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge. I’ve never really seen one up close. Marna and Doug Davis of Shooting Star Enterprises in Hitchcock have some, so we detour a half-hour west.

The Davis’ farm has been in Marna’s family for more than a century. When we arrive, she’s donning an 1870s wrapper farm dress, and Doug is wearing a period-specific three-piece suit and cowboy hat. They call themselves “living historians,” meaning they evolve as they learn more of their subjects. Marna frequently plays Annie Oakley, and Doug does Theodore Roosevelt, whom he resembles. A visit here, we realize, is a bit like teleporting to the late nineteenth century.

Inside, we find a barn-sized, vaulted-ceiling addition to the house where their thirteen-year-old daughter Gabrielle is watching TV in the far corner. But the room is basically a museum, with shelves and walls and tables neatly filled with memorabilia from decades long past. I walk slowly past century-old furs, mounted trophies, various hats and suitcases, a tuba, a piano, neatly stacked shotgun shells, spinning wheels and looms, two shelves of flashlights, lures, and fishing rods.

“Custer carried an identical one on campaign,” Doug says of one of the rods.

Then Marna shyly asks if we’d like to see her room. Wait, there’s more?

“It’s . . . chaotic,” she warns.

Doug Davis has lived along the Chisholm Trail for more than 16 years.

Marna makes period-accurate dresses and accessories—including the parasols for the 2003 Civil War film Cold Mountain. Marna’s room is indeed chaotic. Dress patterns are strewn over bolts of fabric and worktables. Bustle dresses hang on dress stands. Her fashion sense is strictly territorial—1860s to statehood in 1907.

“That’s when dresses started to get less interesting,” she says.

Some of her vocabulary is even older than her dress patterns. I hear her twice use the word harridan, which I later discover—via a circa-1700 British slang dictionary—means “a decayed strumpet.” She leads us to racks that hold her fashion magazine collections from the period.

“I actively look for Demorest magazines. My favorites,” she says. “I’m an eBay fanatic.”

Before we meet their herd, Kim and I are invited to change into farm wear from the Chisholm Trail era. Kim gets into a high-neck button-up farm dress with a sash; I’m in pants, vest, a flowing shirt, and a cowboy hat. Long live 1867! Outside, the Davis’ longhorns already know we’re coming. As we enter the gate next to the house, about two dozen are scurrying over for snacks. They’re big, beautiful creatures with giant horns. Their colors vary wildly, as if someone sprayed them with a water sprinkler filled with black, burnt red, toffee brown, and cream paint.

Gabrielle is with us too, wearing shorts, a T-shirt, and turquoise cowboy boots. She regularly shows longhorns.

“I can’t explain how much you get connected to them,” she says as I pet one named Keepsake. “They just make your life whole.”

The longhorns head off once the snacks are gone. This is our cue for dinner. In the wide backyard, Marna stirs a spicy beef stew from a giant iron pot on an open fire, and we sit to eat outside as dusk falls. The lemon cookies are from a circa-1900 recipe. We swap tales. Doug regularly lets out huge, hearty laughs.

At Marna’s prodding, Doug tells “Andy stories” of a tenderfoot California cowboy he once knew who made goof after goof years ago. Another cowboy he knew, Justin, was better fit for the range; he once wrestled an elk to the ground by its antlers. So when a pause comes, I pipe in.

“Did I tell you about the time I got bit by my gerbil and fainted?” I ask.

A lot of laughter follows. And I’m thinking, in many ways, this is as close to a real Chisholm experience as we could hope for in 2017—sitting by a fire, eating hot food, wearing nineteenth-century outfits, hearing moos, and swapping stories. Some of them are even true.

Kim’s liking it enough to suggest relocating to Oklahoma to set up something called “Coffee Barn” for towns without Starbucks. Ha! Oklahoma is pulling away in a landslide!