The Witness Bearers

Published April 2020

By Liz Blood | 18 min read

Within minutes of the Oklahoma City bombing, local journalists were on the scene to report the unfolding events to the world, often putting themselves in danger to do so. Years later, the trauma of that day still haunts them. But their struggles have contributed to a new field of study that may help reporters better cope with the events they cover.

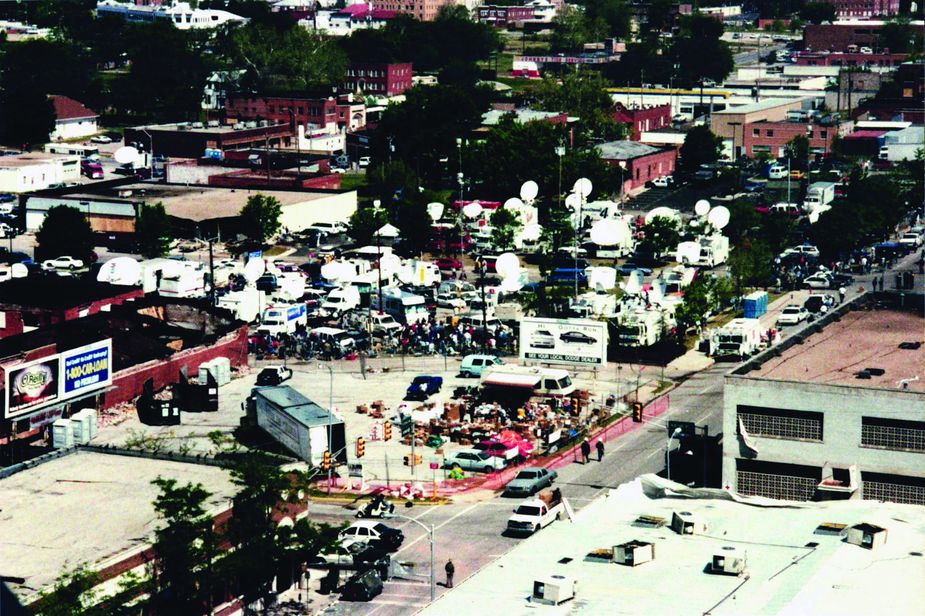

News media from around the world gathered in downtown Oklahoma City following the April 19, 1995, bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building. Photo by Oklahoma City Fire Department/Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum.

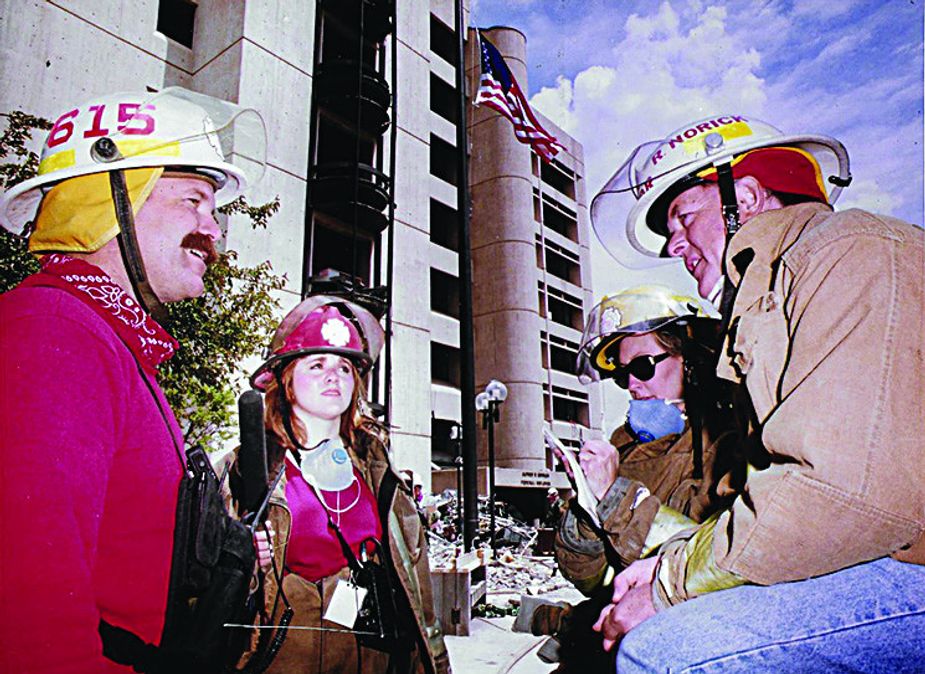

When a truck bomb detonated outside the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City on the morning of April 19, 1995, Oklahoma City’s police department, firefighters, EMTs, and local emergency rooms quickly were overwhelmed. The city’s 911 center recorded 1,800 calls in the first hour after the blast, and first responders raced downtown. Within an hour, additional staff from state agencies, the National Weather Service, the United States Air Force, the Civil Air Patrol, the American Red Cross, and the Oklahoma National Guard were on hand.

Also among those on the scene in the early hours were local journalists who’d come to track the events—and report them to the world as accurately as possible—as they unfolded. Against a backdrop of chaos and tragedy, these reporters found themselves thrust into a situation that endangered their lives. For many, the trauma of that day lingers even after twenty-five years.

In April 1995, Carrie Hulsey-Greene was a reporter for Oklahoma City radio station KTOK. She was in her car at Northwest Fourth Street and North Harvey Avenue when Timothy McVeigh’s bomb detonated at 9:02 a.m. She assumed a gas leak had led to an explosion. Her first radio broadcast of the morning began thirty seconds later. Eventually, she met up with her colleague Trey Davis and climbed into his van. As they drove north on Harvey, they saw Sergeant Bill Martin of the Oklahoma City Police Department running toward them. He was yelling at them to get back—authorities thought they had found another explosive device. They drove the van into an alleyway and hid there.

Carrie Hulsey-Greene, photographed atop what in 1995 was the Journal Record building and now houses the Oklahoma City National Museum, was one of the first journalists on the scene on the morning of April 19, 1995. Photo by John Jernigan.

Steve Lackmeyer, who has been a reporter for The Oklahoman — then The Daily Oklahoman — since 1990, has a similar memory.

“I started walking down Robinson,” he recalls. “Not long after, there was a scare—they thought they’d found another bomb, and everyone started running.”

Later, Lackmeyer and his colleague Steve Sisney were standing near Rebecca Anderson, a nurse who was trying to help victims, when she was struck by falling debris and mortally wounded. Witnessing the day’s many tragedies was traumatic for Lackmeyer and many other local journalists, but covering the bombing and its aftermath also provided an outlet over the next few years.

“I know if I’ve ever felt like I had a purpose, it was then,” says Penny Owen, who was a reporter on The Oklahoman’s police beat that day. “Therapy for me also came in the form of just doing my job. I knew that people were relying on the paper.”

Terri Watkins was reporting for Oklahoma City affiliate KOCO and says focusing on work was, for her, the only way to make it through the experience.

Terri Watkins, photographed near the Survivor Tree, was an investigative reporter for KOCO-TV and was early on the scene of the bombing. Photo by John Jernigan.

“I was working through it, which, for me, is the way to handle something,” she says. “It was not difficult to do my job that day; it was my comfort zone.”

Still, both women report they experienced major emotional come-downs in the weeks and months following. For Owen, it happened when she got back to Oklahoma in 1998 after reporting on McVeigh’s and Nichols’ trials in Denver.

“It was like falling off a cliff,” she says.

For Watkins, some difficulty arose as she watched onlookers, many of whom were families of victims, observing the implosion of the Murrah Building’s remains. Phil Bacharach, who then was a reporter for the Oklahoma Gazette and covered the aftermath and trial for nearly three years, says the focus on work had a dark side.

“I think it just took a toll on me,” he says. “Not just in terms of trauma—but in terms of obsession.”

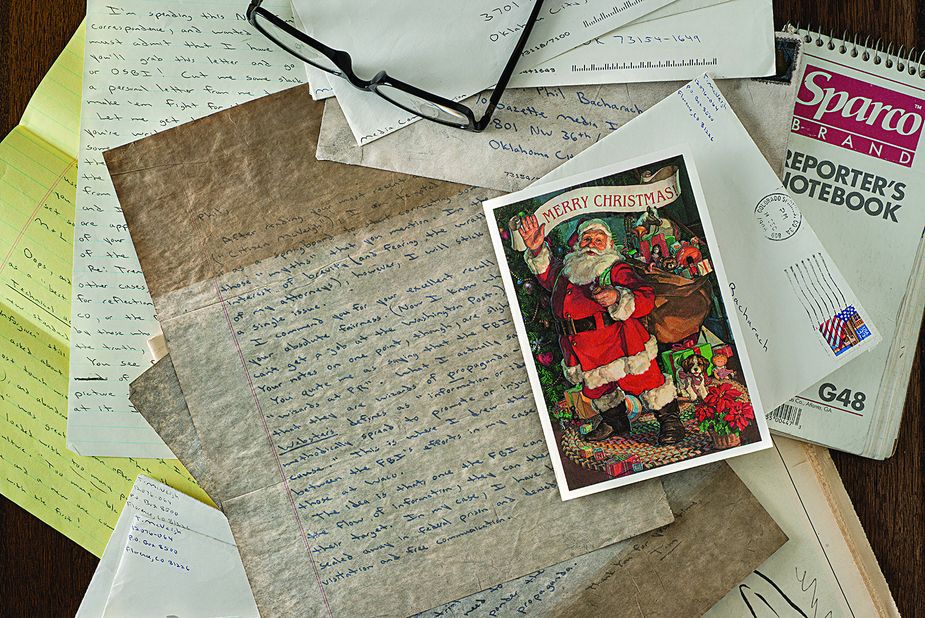

In 1996, Phil Bacharach, then a reporter for the Oklahoma Gazette, began a correspondence with Timothy McVeigh that included a Christmas card from prison and became the subject of a 2001 Esquire cover story. Photo by John Jernigan.

Bacharach’s obsession took the form of a correspondence with McVeigh that later became a 2001 cover story for Esquire magazine.

“There was this layer of guilt and shame for this relationship I had built with him,” Bacharach says. “When I went in to cover the trial in Denver, my first day there, McVeigh came into the courtroom, and he scanned the gallery. I guess he saw me; he kind of nodded his head very briefly in acknowledgement, and it was not lost on the woman I was standing next to, who’d lost her grandchildren in the bombing. She said something like, ‘Huh, will you look at that.’ It was rough.”

Twenty-five years later, those who reported on the bombing still reckon with challenges from that day and the years that followed. Lackmeyer was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder. But, he says, getting the care he needed was difficult.

“I didn’t get treatment then, because I saw a fellow reporter making fun of another reporter who cried during a group therapy session at work,” he says. “I was like, ‘Nope, I’m not going to be made fun of like that.’”

Carrie Hulsey-Greene, left of center, reporting in front of the Murrah Building in 1995. Photo by David McDaniel/Oklahoma Publishing Company.

When Lackmeyer was assigned to report on one of the bombing’s anniversary ceremonies, he called his editor and said he couldn’t do it. However, in May 1999, when a tornado outbreak struck central Oklahoma communities including Bridge Creek and Moore, he went to report on the devastation. The sight was similar to the wreckage around the Survivor Tree and triggered many of the feelings he’d experienced at the Murrah Building, but he powered through. Years later, he says he has found counseling helpful and believes journalists should receive mandatory training in dealing with trauma.

“You’d have to require it, because some people would refuse out of ego,” he says. “Have a trauma counselor come in and train people on what they should look for in covering a disaster.”

Other journalists who reported on April 19 aren’t so sure, however.

“I don’t know if there is training you can do for that,” says Watkins. “We were all going about our lives, and the world changed. I don’t know how you prepare people to deal with that.”

Since 1995, it has become more common to think of journalists as first responders like police, fire, and medical personnel. Though the historic conception of journalists is as neutral observers simply reporting the facts, an emerging field of study suggests they undergo much the same experiences as other first responders.

Elana Newman is McFarlin Professor of Psychology at the University of Tulsa and research director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma, and she has spent much of her more-than-twenty-year career studying the intersection of trauma and news gathering. When she began, this was an unknown field of inquiry. According to the book Covering Violence: A Guide to Ethical Reporting About Victims and Trauma by William E. Coté, first published in 2000, the only research about the effects of trauma on journalists published before 1999 was a study of fifteen reporters who witnessed an execution in a gas chamber. When Newman first submitted academic articles on the subject in the late 1990s, she found publication next to impossible.

Penny Owen was a reporter for The Oklahoman who covered the bombing and McVeigh’s and Nichols’ subsequent trials in Denver. Photo by John Jernigan.

“Only in recent years is it in the peer-reviewed literature,” she says.

The Dart Center was founded in 2000. The next year, the attacks of September 11 provided an inflection point for researchers to look at the way journalists are affected by the events they cover. Since then, Newman and her students have found more than 2,200 academic articles that mention trauma and journalism. Still, only 1.8 percent of those articles discuss the effects of trauma on news organizations, and only 2.3 percent discuss training journalists to deal with trauma. Clearly, there still is much to learn. In the meantime, Newman believes training may help reporters be better prepared to handle unexpected and violent experiences.

“It won’t account for everything, but there are principles and ideas just like in hostile environment training,” she says. “There is the element of not being able to fully prepare, but if that were the case, cops wouldn’t prepare, ambulance drivers wouldn’t prepare, firefighters wouldn’t prepare. You can’t prepare for every safety concern, but it helps you start thinking about the issues you might face.”

Hulsey-Greene believes such help could go a long way. She suggests something as simple as providing reporters with a list of feelings to expect during and after the experience.

“At the very least, it would keep you from wondering why you’re feeling that way,” she says. “You wonder, ‘Why am I feeling like this? I didn’t lose my life; I didn’t lose anyone. I’m just doing my job.’”

News organizations providing this training have seen it as a predictor of resiliency, while a lack of preparation has been shown to correlate with workplace dysfunction.

“The two outcomes are PTSD and a pretty global measure of work dysfunction like missing deadlines, being late, and yelling at colleagues, among others,” says Newman. “So we’ve shown that lack of training predicts the negative, and training predicts the positive.”

Reporters regularly visit war zones, disaster areas, and the sites of mass shootings, and still, the pressures of the job keep many from seeking help in dealing with what they see. In a piece in Nieman Reports’ Fall 1996 issue titled “Reporters Are Victims, Too,” another Oklahoman reporter, Charolette Aiken, recounts the harrowing first day reporting on the bombing—and why so many in her field were reticent to express the effect it had on them.

As officials and responders worked around the clock, reporters clamored for answers in the wake of the bombing. While worldwide media focused on the day’s events, local journalists were the first to tell the story as it unfolded. Photo by Oklahoma City Fire Department/Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum.

“News people are almost as bad as the macho types some of us report on,” she writes. “To admit feelings of depression, fear, or anxiety is to admit you can’t cover the beat. We mostly keep those feelings buried deep inside.”

With improved research and training, this slowly is changing. Many of the ways journalists found to cope were improvised in Oklahoma City after the bombing.

“Like remembering the victims,” Newman says. “That was an innovation then; now, it’s standard practice.”

On April 19, 1995, Joe Hight was the community editor at The Daily Oklahoman and was responsible for the individual profiles of victims the paper published. The idea, he says, was not to write simple obituaries but to honor victims’ lives. Today, Hight is the endowed chair of journalism ethics at the University of Central Oklahoma, and he believes the reporters’ consideration of the community impact of their work has influenced newsrooms across the country.

“That’s why the Memorial Museum features journalists as part of its exhibit,” he says. “But I always worried about the people who did that work, and I still do today.”

Hulsey-Greene continues to walk what she calls the guilty-grateful line.

“Living on that line is hard, because every time you feel guilty about living, you have to tell yourself you should be grateful,” she says. “And then you start feeling grateful, and you’re like, ‘I have all this stuff, and these other people don’t.’ It just goes back and forth.”

Journalism can be a deeply competitive field, and the perceived stigma of not being able to handle it keeps many from getting the assistance they need.

“There’s this idea that you shouldn’t be part of the story,” Newman says. “Because you are a professional bystander, it makes it so much harder to admit you have a reaction. We downplay how wearing it is to be constantly dealing with people in grief. The emotional burdens of bearing witness haven’t gotten enough attention.”

For Hight, however, it was the empathy of Oklahoma City’s local journalists that made their work that day—and in the months and years that followed—so vital.

“I’ll never forget journalists crying on the first anniversary,” he says. “It’s always sad, wherever I am, when that anniversary comes. It will be incredibly sad on the twenty-fifth. But if we don’t feel that sadness, I question why we are journalists.”