Tulsa's Dance with Destiny

Published July 2024

By Ben Luschen | 21 min read

The first time JD McPherson ever stepped inside Tulsa’s legendary Cain’s Ballroom, he’d just barely hit his teenage years. At that age, the Talihina kid could not have fully grasped the legacy of Bob Wills—not anywhere near as well as the older folks gathered around him. They'd lived the glory years. Now they sit silver-haired in a stuffy hall, watching the past come alive at a Bob Wills Birthday Bash. They pack pews set out in rows on the old worn dance floor.

This guitar-playing youngster dragged by family to a Wills tribute would go on to get write-ups in Rolling Stone, tour on multiple continents, and headline the Cain’s stage on many occasions. In this moment he was just a kid, but the reverence in the room was not lost on him.

“In my mind, Cain’s Ballroom was sort of registering as a church,” recalls the acclaimed Tulsa-based singer-songwriter. “It’s always had this sort of sacred aura to me.”

Cain’s Ballroom looks a lot different in 2024: a high ceiling, a sleek new dance floor, and an adjacent building annexed as a space offering preshow dining, room to mingle, and most importantly, spacious restrooms. But the crown jewel in Tulsa’s claim as Oklahoma’s music capital celebrates its hundredth birthday this year, and a lot from the past remains as it always has been. Just look at the walls, where thirty large portraits of country music royalty hang as they have since they were put up in the 1950s. Some of the stories they’ve seen unfold will be told for ages to come. Some will never be repeated. All of them are bricks in Tulsa’s factory of dreams and memories.

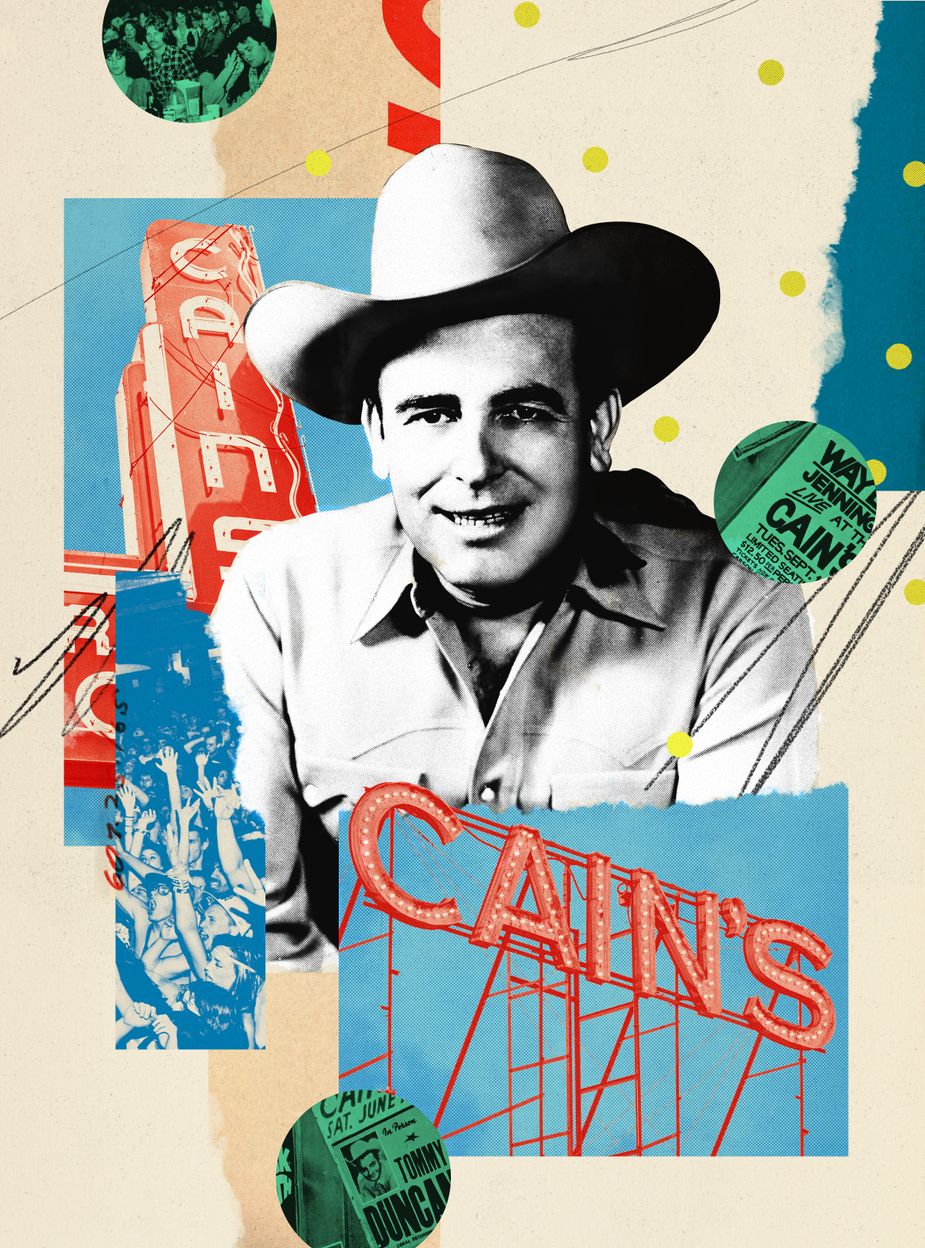

Illustration by Christopher Lee

A half-century before McPherson’s first Cain’s visit, the real show was well underway.

What they called dancing was really just the sway of couples in the shoulder-to-shoulder current. The gentle growl of the standing bass, the fiddle’s cheerful skip, and the cool sunset purr of the lap steel carry Bob Wills’ trademark falsetto and improvised hollers. This beaming West Texan, in a Stetson and plain Western dress matching the band, stared out into the crowd with a relentless smile. The men and women on the floor sweated through their cotton shirts in the summer heat. Bootleggers lurked in the alley, selling whiskey on call.

Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys were not just the biggest show in Tulsa but an obsession of a large chunk of the country. The band broadcast radio shows from Cain’s Ballroom every day on the Tulsa-based radio station KVOO, which could be heard by fans as far as the West Coast, the Midwest, and Mexico. This was the cauldron that birthed and popularized Western swing music—a middle ground between hillbilly country and ballroom dance that won the hearts of many Americans during the Great Depression.

Whether concertgoers are situated on the floor or the balcony, they’re sure to have a good view of the stage. Photo by Kim Baker

Years before Wills arrived in Tulsa, the building now known as Cain’s began life as a garage. As is the case with several other Tulsa cultural institutions, Cain’s Ballroom can trace its roots back to W. Tate Brady, who built the space in 1924 to house his collection of Hupmobiles. Though the businessman and politician played a large role in Tulsa’s early development, his legacy has been reexamined in the city as awareness of his involvement in the Ku Klux Klan and 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre has grown.

Regardless, it’s unclear if Brady’s cars ever actually made it to the building, and his and his family’s role with the property never extended much beyond that of temporary landlord. In fact, Brady himself had already been dead five years by the time Madison “Daddy” Cain and his partner Howard Turner started leasing the place in 1930 for use as a dancing school. The newly dubbed Cain’s Academy of Dancing promoted itself as the “world’s largest school of ballroom dancing.” Aside from his name, which has stuck with the property ever since, Cain’s greatest contribution to the venue’s legacy was installing a maple dance floor, laid with enough give to inspire the common but false assertion that it was spring-loaded.

While Cain is the person who gave the building its name, Bob Wills is the person who gave the place its soul. The Texas Playboys began performing at Cain’s in 1935, shortly after striking a deal with KVOO for daily music broadcasts. As described by the writers John Wooley and Brett Bingham in their 2020 book on Cain’s Ballroom history, Twentieth-Century Honky-Tonk, KVOO had a flamethrower of a signal for the time—it was 25,000 watts when Wills started, and it doubled shortly after. The exposure, plus the band’s new jazzy approach to the Western sound, quickly made Wills’ voice a noontime fixture in many American households. In a time before television, to attend a Bob Wills show was to step inside a scene formerly limited to the same mental domain as dreams and fantasies. Before Elvis, Wills was King.

It would take something major to stop the momentum of the Texas Playboys, and that is exactly what occurred. Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 changed everything for Americans. Many Texas Playboys volunteered to enter the service. This included Wills himself, who left the Tulsa bandleading duties to brother Johnnie Lee. After his short-lived Army experience and subsequent move to California, Bob would return to his former home and join the Cain’s broadcasts on occasion, but the Western swing sound he pioneered was falling out of favor with audiences at home. He never succeeded in recapturing the prewar magic, and KVOO ended all Bob Wills broadcasts from Cain’s by the late 1950s.

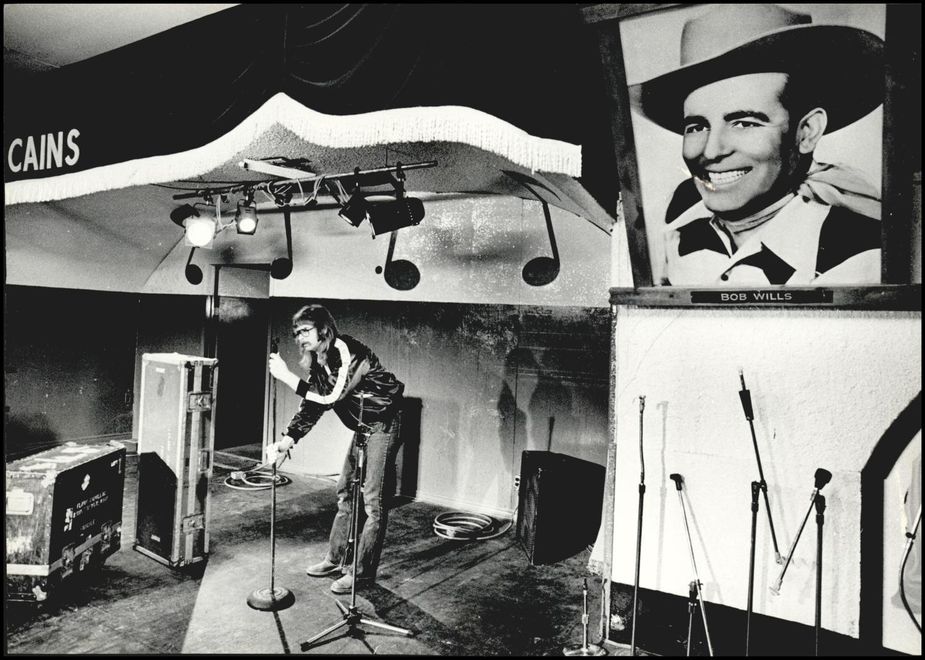

Former owner Larry Shaeffer sets up a mike on the Cain’s stage in November 1979. Photo courtesy Oklahoma Historical Society

Many an old country and western club across the nation endearingly is known by patrons as a hole in the wall, but only Cain’s can claim a hole as a defining feature. A black frame on the wall inside what is today the venue’s ticket and booking office holds a sheet of green drywall with one fist-sized crater through it. A gold plaque underneath reads, “The Sex Pistols’ Sid Vicious left his mark on Cain’s Ballroom by smashing his fist into the wall of the green room on January 11, 1978.”

How did the fist of one of English punk’s most notorious figures find itself wedged inside a wall in the historic Home of Western Swing? It starts with Larry Shaeffer, who was a twenty-seven-year-old Army veteran when he bought the place and renamed it Cain’s Ballroom. He might not have been the perfect businessman or bookkeeper, but he was able to win over artists and booking agents with an air of authenticity and an open-minded approach. In Shaeffer’s twenty-five years as owner of the venue, Cain’s welcomed acts like U2, Metallica, Bon Jovi, Van Halen, Annie Lennox, and more.

“I made so much money I didn’t think I’d need to make any more,” he says, “but I need to check on where it all went.”

Larry Shaeffer owned Cain’s Ballroom for twenty-five years, bringing in some of music’s most well-known acts during his reign. Photo by Shane Bevel

In terms of historical significance, though, one show rises above them all—a concert that would spell the near end of a punk-rock phenomenon.

When people picture a stereotypical punk band, most picture the Sex Pistols: vocalist Johnny Rotten’s leather jackets, chains, torn shirts, and messy, red-dyed hair and shirtless bassist Sid Vicious with a safety pin in his cheek. The band made an impression—and not always a good one. In 1977, they were at the peak of their popularity in Britain, but many local venues would not book them due to their (exaggerated, by some accounts) reputation for offensive, unruly, and dangerous live performances. Not able to tour their home country, the band embarked on its only tour of the United States. In fact, the Pistols intentionally sought venues in the South, where their shows were more likely to stir up controversy and bad press—which they actually viewed as good press. One of those stops was Cain’s Ballroom.

It was a snowy day when the Sex Pistols’ bus rolled up alongside Cain’s on January 11, 1978. Since they’d been scheduled to play in Dallas the night before, no one at Cain’s expected the band to arrive so early. Little did anyone in Tulsa know the chaos that had befallen the band in the Big D—a performance most in attendance said sounded horrible and had ended with Sid covering himself in his own blood. Booze, drug withdrawals, sleepless nights, and plenty of fighting—against others and internally—had plagued all the tour stops.

In the hours between the Pistols’ arrival and their performance, the band acted like the rambunctious young adults they were. At some point, Vicious slugged that famous hole in the wall while testing out a set of brass knuckles.

For twenty years, production manager Brad Harris has directed the logistics of Cain’s shows. Photo by Shane Bevel

Longtime employee Shawn Emig shows off his Cain’s tattoo. He's been working at the venue and attending shows there since 1984. Photo by Shane Bevel

Judging by eyewitness reports, the Tulsa show might have been the band’s most coherent of the tour. An NBC reviewer had described the Pistols’ sound at their Atlanta show as “expressively loud, totally unmelodic, primal driving. It is as ugly as the young men make themselves.” At least one fan who attended the Cain’s show came away with a different impression, as writer Mick O’Shea quotes in his book The Sex Pistols Invade America, “The Sex Pistols were blazing hot that night! The fury and fast-paced music was explosive. It was chaos, the way rock ‘n’ roll ought to be.”

One night of good music wasn’t enough to save the band, though. From Tulsa, the Pistols traveled to San Francisco to conclude their American tour. It was not just the band’s final show in the States but their last set before breaking up for good. No one could survive such a torturous tour. Today, Cain’s stands as the only venue from the band’s American tour that remains open as a concert hall.

Since 2002, brothers Hunter, left, and Chad Rodgers have owned and operated Cain’s Ballroom with their family. Photo by Shane Bevel

Shaeffer’s run with Cain’s would end near the turn of the millennium after nearly a quarter century. With that longevity in mind, it’s daunting to think about how brothers Chad and Hunter Rodgers were just twenty-three and nineteen, respectively, when they took control. Twenty-two years later, things have improved quite a bit. Chad, Hunter, and their parents had already been discussing the possibility of opening a bar and music venue in Tulsa when they heard Cain’s was for sale. They called the real estate agent, and a deal was finalized within a couple of days. No one in the family had experience booking or promoting shows. The first show they put on at Cain’s was a concert by the Charlie Daniels Band.

“We lost probably $30,000,” recalls Chad. “It was scary as all get-out. I remember calling my dad the next morning and almost crying.”

Hands-on experience, it seems, is the best teacher. Despite early growing pains, the Rodgers era has brought acts from Green Day to Bob Dylan to Kacey Musgraves to St. Vincent to the stage. At a time when it is rare to find a performance hall of similar size that is not run by a national corporation, Tulsa’s century-old independent venue is routinely recognized as one of the best and most successful. Cain’s Ballroom was one of five regional venue winners recognized in a 2023 fan-vote campaign by music publication Consequence, and it frequently appears on lists of the top ticket sellers in its size category.

From an elevated booth at the back of the house, audio engineer Jeremy Grodhaus oversees the sound for every show at Cain’s. Photo by Shane Bevel

Chad attributes much of this success to the relationships the family has cultivated through the years with booking agencies. Cain’s always seems attuned to the pulse of music trends and the ever-evolving tastes of its audience.

Another vital aspect to giving Cain’s its new spark was committing to some much-needed updates—most notably a new dance floor. The Rodgers brothers had to replace it on two occasions. The first time was in 2007, when they pulled up the historic maple floor once presided over by Bob Wills. Though legendary, it had become a safety hazard. Sections of the floor where people might have fallen through had to be set off with cones.

“Right in front of the stage, it was like a pond every night,” recalls longtime Cain’s bartender David Standingwater. “If any kind of alcohol or anything hit the floor, it was just a big ol’ pond up there.”

The floor then needed to be replaced again in 2017, after it was found that the previous one had not been properly installed. The current floor even replicates the slight spring effect that made the original famous.

Except for the glow of the Cain’s sign, this is an area of downtown Tulsa that was dark for many years. Now, not so. The Tulsa Arts District is a bright hub of activity nearly any night of the week. Bands with aspirations of maybe one day playing inside the Home of Bob Wills take the bar stage at The Vanguard. Attractions like the nearby Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan Centers and planned OKPOP Museum have sprouted up to assert Tulsa’s status as the state’s premier music destination. At the center of this orbit, vital to the flourishing art and cultural scene around it, is Cain’s, peering down from its hilltop as if on a stage of its own.

“This place has created so many memories,” Rodgers says, “and I think that’s our goal every night—to create a new memory for everyone that’s here.”

.jpeg)

Musician JD McPherson grew up watching shows at Cain's before playing there himself. Photo by Alysse Gafkjen

In 2022, Years after his first visit to Cain’s, McPherson joined his teenage daughters for a show. On stage was girl in red, the indie pop project of Norwegian singer-songwriter Marie Ulven Ringheim. Looking around at the crowd, McPherson saw how much has changed since that Bob Wills birthday party years ago. Peering down at them from the walls, though, were the same sepia-toned mugs of Bob Wills, Hank Williams, Tex Ritter, and all those ghosts of the past.

“You swat away phantoms every time you walk in that place,” McPherson says.

These portraits form a spirit council and in their tireless watch impart a tangible permanence on the confines. It is likely they have not always approved of the things they’ve seen unfold there through the years, and that’s the way it should be. Tulsa is a city defined by the inevitable friction of, at times, conflicting values. For the past century, people have filed into Cain’s as preachers, punks, politicians, and all the other types of labels you can put on folks, but from doors to encore, each of them is one and the same: witness to the best show in town.

.png)