Anarchy in the I.T.

Published October 2021

By Brian Ted Jones | 13 min read

The pre-statehood Panhandle community known as Beer City was a haven for frontier lawlessness, advertising itself as a place with “absolutely no law.” JJ Ritchey

In August 1888, two newspapers reported on the unfortunate death of a twenty-eight-year-old painter named Charley Meyers—or Charles Myers, or maybe Charles Meyer; the name is spelled three ways across the two accounts.

The Indian Chieftain of Vinita related the story: Meyers was standing in a saloon near the saloonkeeper, George Shoemaker, who was handling a revolver carelessly. The gun discharged, and the ball struck Meyers in the arm before entering his stomach. He died within fifteen minutes.

The Wichita Eagle of Wichita, Kansas, had reported the same story two days earlier, adding a few personal details: Meyers was considered a harmless man, and it was said he had two children living with relatives in Colorado. Both papers noted the place where Meyers died was a town called Beer City on the Neutral Strip. The Eagle went so far as to claim Meyers lived there.

Except Beer City wasn’t actually a town, per se. There never was a Beer City post office, a Beer City church, nor a Beer City school. The area was cattle country, but there were no cattle pens in Beer City. The Beer City townsite was never platted. And when the merchants of Beer City pitched their community to prospective settlers in newspaper advertisements, their chief selling point was the town’s lack of any civic code whatsoever. They bragged about Beer City being “the only town of its kind in the civilized world where there is absolutely no law.”

Witnesses claimed the shooting of Charley Meyers was accidental, absolving George Shoemaker of any intentional killing. But in a place like Beer City, would it have mattered?

To understand Beer City and its brief spell of anarchy, one must begin on May 4, 1493, when Pope Alexander VI granted the Spanish crown “all islands and mainlands found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered” on an area of the planet corresponding roughly to the northern half of the Western Hemisphere. This included the rectangle of land measuring about 5,700 square miles that today makes up the Oklahoma Panhandle’s three counties of Cimarron, Texas, and Beaver.

Spain claimed undisputed title to the land until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, which placed the border between the United States and the Spanish empire into serious doubt. In 1819, though, the Adams-Onis Treaty resolved the issue by setting the boundary at the 100th meridian, where the line between Harper and Beaver counties—the Panhandle’s eastern boundary—runs today.

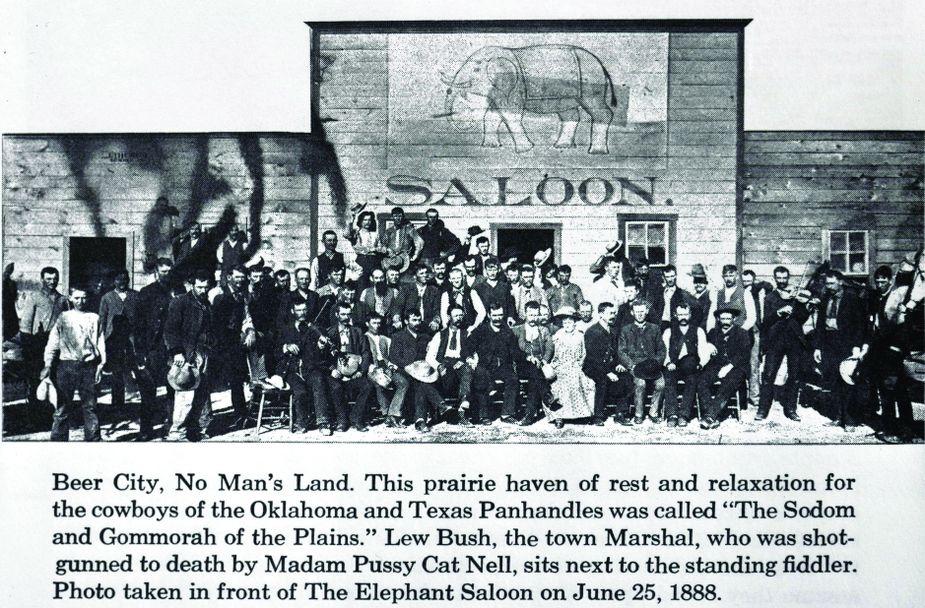

Beer City came to be known as the “Sodom and Gomorrah of the Plains.” In this photo taken in front of Beer City’s Elephant Saloon on June 25, 1888, the town’s self-appointed sheriff, Amos Bush, sits next to the fiddler at the right of the photo. Local businesswoman Pussy Cat Nell and a posse of fourteen men later shot Bush to death. Western History Collections/University of Oklahoma

President John Quincy Adams signed the treaty confirming Spanish control over the area on February 22, 1819. But on August 24, 1821, Spain would lose the Panhandle to Mexico in the Mexican War of Independence. Then in 1836, Mexico lost the land to Texas in the Texan War of Independence. For 328 years, the Panhandle had belonged to Spain, but in less than seventeen, the area passed from Spain to Mexico, then from Mexico to the Republic of Texas.

The United States annexed Texas in 1845, bringing the Panhandle under U.S. authority for the first time. But the Missouri Compromise of 1820 prohibited Texas from keeping both the Panhandle and the institution of slavery, since the Compromise prohibited slavery north of the very latitude line which now forms the area’s southern border.

In 1850, to solve this problem, Texas ceded an enormous chunk of land to the federal government, including the future Oklahoma Panhandle. Most of the ceded land quickly became organized into the Kansas and Nebraska territories in 1854, in part to speed up construction of the Transcontinental Railroad. The Panhandle would probably have become a part of Kansas, except the 1836 Treaty of New Echota between the U.S. and the Cherokee Nation had guaranteed the Cherokees “a perpetual outlet west” with “free and unmolested use” as far west as “the sovereignty of the United States and their right of soil extend.”

To protect this Cherokee Outlet, the tribe successfully objected to the federal government placing the Kansas border too far south. After drawing the territorial lines for Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas, Congress left intact and unclaimed the zone of land due west of the Outlet. For the first time in almost four centuries of Western history, the Panhandle became a distinct place with a formal name: the Public Land Strip or Public Land.

From 1850 until 1890, the Strip was not entirely ungoverned. The influence of the Cherokees could be felt in the grazing fees early Panhandle cattlemen paid the tribe to feed their livestock on its abundant grasses, and the U.S. Postal Service even erroneously called the area “the Neutral Strip of Indian Territory.”

This prompted an inquiry by a Strip resident to the U.S. General Land Office in 1885. The Office ruled the Strip wasn’t part of Indian Territory at all, and a Supreme Court opinion the same year held the Cherokee Nation possessed no rights to the Strip. These developments immediately opened the area for settlement by squatters, in a space where no government—state, territorial, or municipal—prevailed.

The final step toward the creation of Beer City came in 1888, when the Santa Fe Railway extended its line southwest from Liberal, Kansas, to the town of Tyrone, in what’s now Texas County. In Tyrone, big, sturdy corrals were constructed, and the cattle market blossomed, while cowboys and cattlemen sought liquid recreation after their long drives to market and long days haggling over livestock prices. But these recreations weren’t to be found under the strict anti-liquor laws in Kansas.

And so, in a spot northeast of Tyrone, on the Strip side of the Kansas border, white tents began appearing in 1888 containing pop-up saloons, brothels, and gambling houses. The new community began its short life as “White City,” in honor of these tents, but quickly became more well-known for the enthusiastic revelry there. It took on the blunt name Beer City.

Even after the area now known as the Oklahoma Panhandle became part of the United States in 1845, land-use issues kept the area mired in legal confusion. In 1886, Interior Secretary L.Q.C. Lamar declared the area to be public domain and subject to squatters’ rights. Steven Walker

In modern terms, Beer City’s economy depended entirely on tourism. Games of chance were available at several locations any time of the day or night. Liquid refreshment could be purchased tax-free from a still built in a cave under a lean-to near a stream called Hog Creek. What Dan Burle Sr., author of Frontier Justice, called a “melange of red lights, saloons, and dance halls” offered entertainment in the form of wrestling matches, boxing bouts, horse races, and Wild West shows, which they could provide for free from all the money brought in by gambling and alcohol sales. Sex workers migrated to the area in heavy numbers during cattle-shipping season; many of them resided in Liberal and commuted back and forth to Beer City. And though there was no law in Beer City, those who visited could not say the place lacked order. Local businessmen hired enforcers to keep con artists, pickpockets, and holdup men from robbing their customers.

A local cattle rustler named Amos “Brushy” Bush declared himself the town’s marshal on no authority higher than his own word—and the combination of a six-shooter and a sawed-off shotgun he carried. Bush ate, drank, and slept wherever he pleased and took his salary in tributes from Beer City merchants.

He pushed his authority too far, though, in July 1888, when he demanded an exorbitant tax from Pussy Cat Nell, who managed the second floor of the Yellow Snake Saloon. Nell refused to pay, and Bush beat her up. Nell waited, watching the street through her window, and when Bush passed by, she shot him where he stood—in full public view. Several bystanders who saw that Bush had fallen by Nell’s bullet also fired at Bush, so no one could say for certain Nell had been the culprit.

Bush survived, ran for mayor, lost, and threatened to murder everybody in town. The people of Beer City held a meeting and reached a consensus: Bush ought to shut up, or better yet, leave Beer City forever. He refused to do either and died shortly thereafter, his body found riddled with seventy-four bullets fired by Pussy Cat Nell and a posse of fourteen men.

Four centuries of history had conspired to produce Beer City’s two-year burst of lawlessness. But in 1890, Congress passed the Oklahoma Organic Act, which added the Public Land Strip to Indian Territory. Since liquor was forbidden in the territory under an 1834 statute requiring strict prohibition in any place defined as Indian Country, beer no longer could be sold in Beer City.

The town—such as it was—disappeared forever. But its legacy persists as one of the places that truly put the wild in Wild West, a testament to a time when the American frontier was facing the push and pull of an expanding United States—and the rule of law that came along with it—and the total freedom so many had come to the West to find.

.png)