West World

Published November 2019

By Susan Dragoo | 24 min read

West World

By Susan Dragoo

Low clouds and a biting wind make for a bleak, eye-watering day on the prairie. Along a quiet road twelve miles south of Ponca City, I walk among the remains of the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch headquarters. A silo and the shell of a powerhouse stand west of a trio of foundations: a hotel, the ranch store, the Millers’ family home. Among the solemn ruins are oddities as well: what’s left of a monkey house and a manmade cave built for a pet black bear.

This is my third visit, and each time, I’ve had the place to myself. But the site’s lonesome aspect belies both its former glory and the long-term significance of what happened here. At its peak, the 101 Ranch encompassed more than a hundred thousand acres and included land in four counties. Though it was noteworthy for its size, scope, and the success of its livestock and farming enterprises, its lasting impact was the role it played in making Oklahoma the epicenter of Western films at the dawn of motion pictures.

“I would even be so bold as to say Oklahoma was the cradle for the birthing of that whole genre of Western films, which caught on like prairie fire all through the twentieth century and still burns on today in many hearts and minds,” says Michael Wallis, author of the 1999 book The Real Wild West: The 101 Ranch and the Creation of the American West.

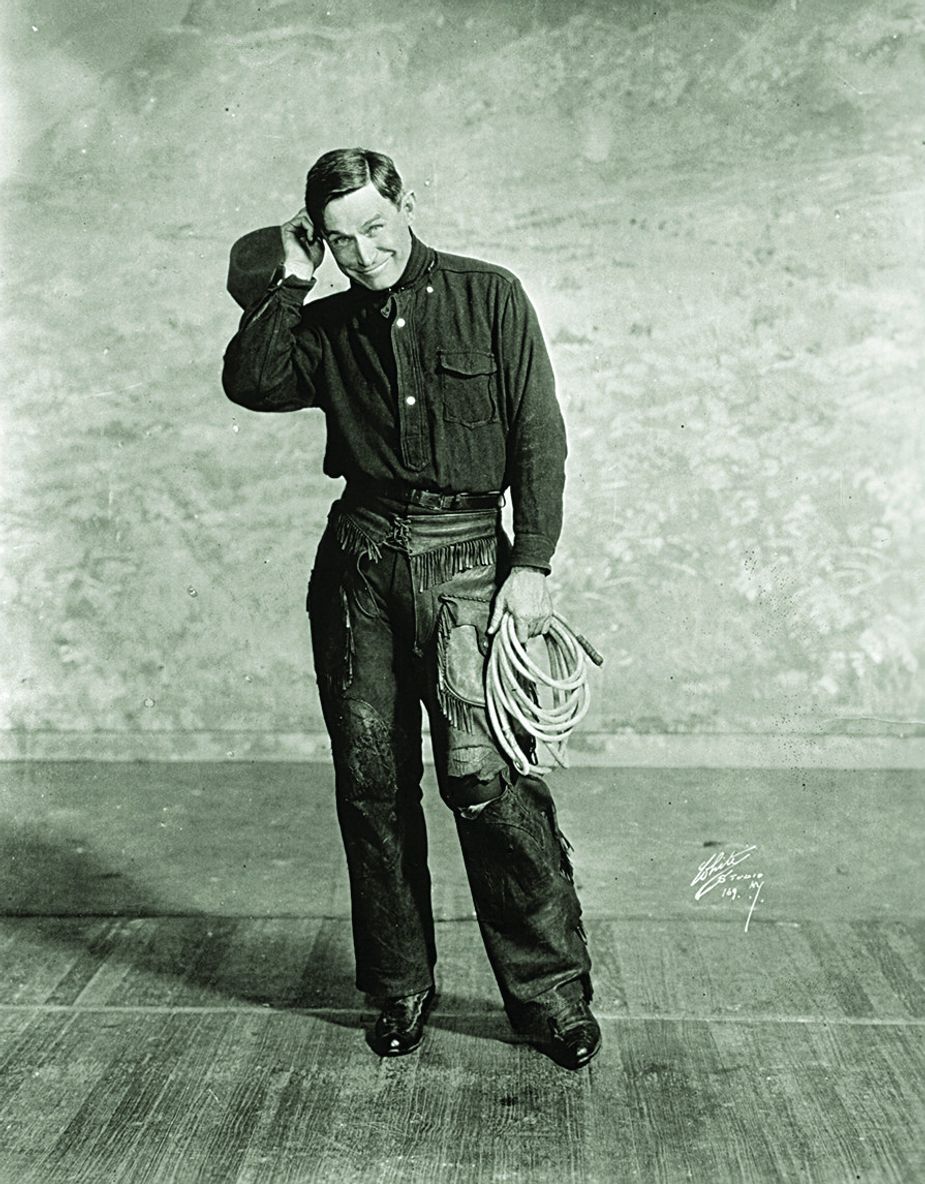

Cinema star, rodeo legend, and occasional bartender Tom Mix appeared in the silent film "Mr. Logan, USA" in 1919. A museum in Dewey honors Mix’s legacy. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Westerns depict struggle and heroism—often highly romanticized—on the frontier of the United States mostly after the Civil War. They comprised one of the most popular film genres of the early cinema period, making up nearly a fifth of all features from the silent era through the 1950s. Blending myth and reality, they thrilled audiences with showmanship adapted from Wild West shows and characters presented against the backdrop of the vast American landscape.

Tracing the history of Western movies through Oklahoma unveils a fascinating chapter in the state’s history, a window to a past full of adventure. Thanks to experts like Wallis, there’s a clear path to follow, and it leads from the Tallgrass Prairie Preserve in the northeast to the ancient Wichita Mountains of the southwest.

The trail starts at—then returns again and again to—the 101 Ranch headquarters on the north-central Oklahoma plains. It was here in September 1893, with the opening of the Cherokee Strip, that cattleman G.W. Miller and his family staked their claim on grazing lands along the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River, officially founding the 101 Ranch.

As the Miller enterprise flourished and diversified, forces of change in the eastern U.S. were on a trajectory to intersect with the family’s fortunes. Public exhibitions resembling Wild West shows had been around in one form or another for centuries, but William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody brought them into full flower in 1883, entertaining crowds in a circus-like atmosphere with feats of marksmanship, horseback riding, rope twirling, and re-enacting exciting Old West scenarios. These shows glamorized reality and played a major role in creating the enduring myth of the Wild West.

Thomas Edison patented a motion picture camera in 1891 and publicly exhibited the first movie in New York in 1893. At first, short, nonfiction films called “actualities” were viewed one person at a time in kinetoscopes, or peep shows. Some contained scenes of performers from Cody’s Wild West show, including Annie Oakley, Native American dancers, and a bucking bronco.

With the invention of the film projector and the advent of theaters dedicated to showing movies—dubbed “nickelodeons” because admission was five cents—cinema in America picked up steam. Films got longer and began to tell stories. In 1903, Edwin S. Porter produced and directed the first narrative Western film, The Great Train Robbery, revolutionizing filmmaking with its use of editing versus shooting everything in sequence.

Bennie Kent’s camera is displayed at the Lincoln County Museum of Pioneer History in Chandler. Photo by Susan Dragoo.

“The thing that makes The Great Train Robbery most relevant to the beginnings of the movie industry in Oklahoma was its Wild West-flavored, cowboys-and-outlaws setting,” writes historian John Wooley in* Shot in Oklahoma*, a history of Sooner State filmmaking. “A few years after the turn of the last century, a general feeling had begun to creep into the American culture that suggested the days of the real Old West were over, that progress and technology had rendered the frontier, and the rugged individualists who tamed it and lived and loved and fought in it, obsolete.”

This nostalgia for the Old West increased the public’s appetite for stories set on the frontier, and one of the attractions of filming in Oklahoma Territory was its authentic Western settings and people. In 1904, Thomas Edison sent a film crew to the 101 Ranch, marking the genesis of filmmaking in Oklahoma.

“They’d set up a camera, and there’d be cowboys and Indians fording a river, and that’d be about it,” says Wooley.

But it was a start. Most of these early movies were actualities. But three short fictional films were made at the 101 in 1904 and 1905:* Brush Between Cowboys and Indians*, Western Stagecoach Hold Up, and Western “Bad Man” Shooting Up a Saloon.

Even President Theodore Roosevelt got in on the act. He traveled through the Wichita Mountains in 1905 with John R. “Catch ‘Em Alive Jack” Abernathy, who captured wolves with his bare hands. Met with skepticism upon returning to Washington, DC, Roosevelt wanted Abernathy’s feat filmed. In 1908, pioneering Oklahoma cameraman James “Bennie” Kent of Chandler filmed an Abernathy hunt in the Wichita Mountains and, the same year, shot movies with Marshal Bill Tilghman and outlaw Al Jennings, who played themselves in The Bank Robbery and* The Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws*. Kent was Oklahoma’s first cameraman and would go on to work for the Miller Brothers, eventually heading up their motion picture production department.

When the oldest Miller son, Joe, took the reins of the family business after the passing of his father, he was eager to showcase the operation he was running with his brothers George and Zack. In 1904, he convinced the National Editorial Association to hold its 1905 convention in Oklahoma Territory, with the highlight to be a bison chase and cowboy reunion at the 101 featuring riding and roping performances by the ranch’s cowhands and showpeople. The event was dubbed “Oklahoma’s Gala Day.”

International celebrity Will Rogers rose to fame as a silver-tongued rodeo roper. Photo courtesy of Will Rogers Memorial Museum.

As a prelude to their big exhibition, the Miller troupe accepted an invitation to appear with Colonel Zack Mulhall’s Wild West show in New York City. There, they performed alongside young trick roper Will Rogers, a close friend of the Millers. During the Madison Square Garden performance, as cowgirl Lucille Mulhall prepared to lasso an eight-hundred-pound steer, the animal jumped over a gate and into the stands. Spectators fled as other cowboys tried to capture the beast, but, as the legend goes, it was Rogers who roped the steer and saved the day. His feat attracted the attention of vaudeville promoters, and they convinced him to stay in New York after the Mulhall show closed. Soon, Rogers was headlining his own roping act, leading to successful engagements with the Ziegfeld Follies and the first of many movie contracts. He played the role of a comic cowpuncher in many of his films, and more than eighty years after his 1935 death in a plane crash, Will Rogers still is Oklahoma’s beloved native son.

Back at the 101 Ranch, on Gala Day—June 11, 1905—from a grandstand more than a mile long, a crowd of 65,000 marveled at the pageantry of marching bands, re-enactments of a bison hunt and a wagon train under attack, feats of riding, roping, and marksmanship, and even famed Apache warrior Geronimo, who was paraded out in an automobile to shoot a bison.

(While the animal in question was billed as Geronimo’s last bison kill, it was, in fact, the first one he’d ever shot.)

Though staged for the convention of editors, Gala Day attracted spectators from across the country. It was a stunning success and a watershed moment for the Millers, and the presence of the national media assured word spread far and wide.

Three months after Gala Day, the Miller Brothers took their 101 Ranch Real Wild West Show on the road, beginning a heyday of travel all over the United States as well as Mexico, Canada, South America, and Europe. In 1911, the 101 troupe wintered in southern California, a vacation that led to their involvement with the infant movie industry. The Millers’ West Coast film production, using 101 Ranch performers and stock, launched the careers of movie cowboys who became household names across the country.

101 Ranch hands who became big in Hollywood included Hoot Gibson, Buck Jones, and Ken Maynard. Yakima Canutt, who performed with the 101 in 1914, became a Hollywood stuntman and, according to Wallis, taught John Wayne to ride a horse and walk like a cowboy.

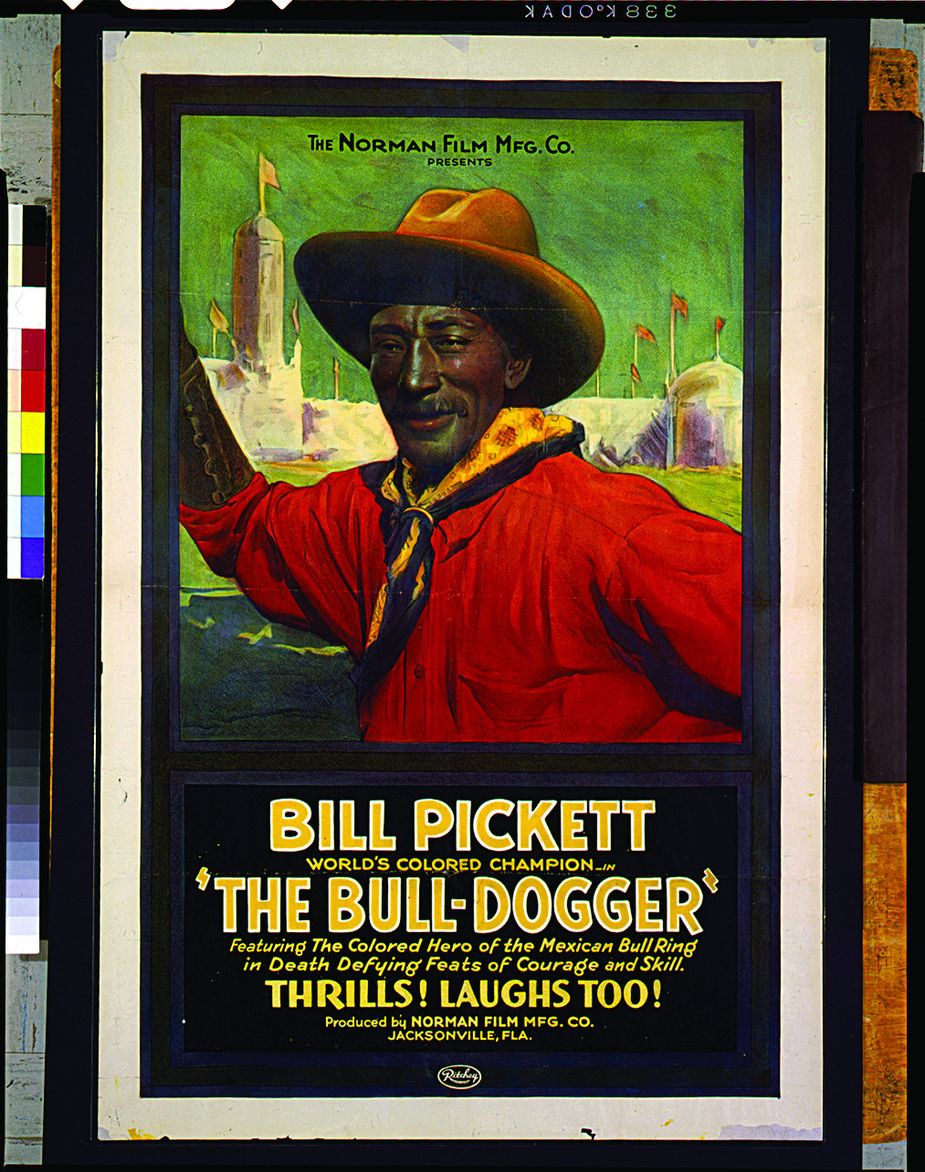

With films like "The Bull-Dogger," 101 Ranch hand Bill Pickett gained fame as a movie actor. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Another 101 performer who made a lasting impact was Bill Pickett, who originated rodeo steer wrestling, or “bulldogging,” grabbing a steer by its horns, twisting its neck, biting its nose or upper lip, and making it fall to the ground. Pickett performed in Western films like 1921’s Crimson Skull and 1922’s The Bull-Dogger and was the first African-American cowboy movie star.

Like the Millers, Gordon W. “Pawnee Bill” Lillie used his Wild West show and ranch near Pawnee to attract outside filmmakers, and he produced four films of his own. The Wild West show still thrives at the Pawnee Bill Ranch and Museum, which annually produces a colorful re-creation of Lillie’s spectacle every June. And the ranch museum displays posters and still photos from Lillie’s films. Movie making continued on the Oklahoma ranch as well.

“During the first three decades of the twentieth century, nearly every film, especially the Western movies with an Oklahoma connection, could have been traced to the Miller family or to one of their associates,” writes Wallis.

During the first three decades of the twentieth century, nearly every film, especially the Western movies with an Oklahoma connection, could have been traced to the Miller family or to one of their associates. Michael Wallis

Very few of the films made in this era have survived, but a three-room exhibit at the Marland Grand Home in Ponca City, maintained by the 101 Ranch Old Timers’ Association, is brimming with artifacts that tell the age’s story.

I ask Michael Wallis how best to connect with the legacy of the 101, and he tells me, after visiting the Ponca City exhibit and the historic site, to head to the Woolaroc Museum & Wildlife Preserve, where the Millers spent a great deal of time in the company of their good friend, the oilman Frank Phillips.

I arrive at Woolaroc the next morning, and the place fairly glows on a sunny day. Twelve miles southwest of Bartlesville on State Highway 123, Phillips’ ranch, a fine combination of manicured and wild, is a preserve for bison, elk, and exotic animals. Phillips’ museum, founded in 1929, holds collections of Native American artifacts, art, firearms, and relics of the Old West, including Joe Miller’s jeweled saddle and other 101 Ranch pieces. Inside Phillips’ preserved lodge home, the color and warmth of the prairie décor is suited perfectly for visits by the Miller brothers and other Osage Hills denizens.

The trail next leads me north of Bartlesville to Dewey. Tom Mix joined the 101 team in 1905 and became the highest-paid Hollywood star of his day. He lived here briefly, and the town pays him homage with its Tom Mix Museum. Downtown, across from the historic and period-accurate Dewey Hotel Museum, it houses a collection of memorabilia and puts on an annual Tom Mix Festival and Western Heritage Weekend.

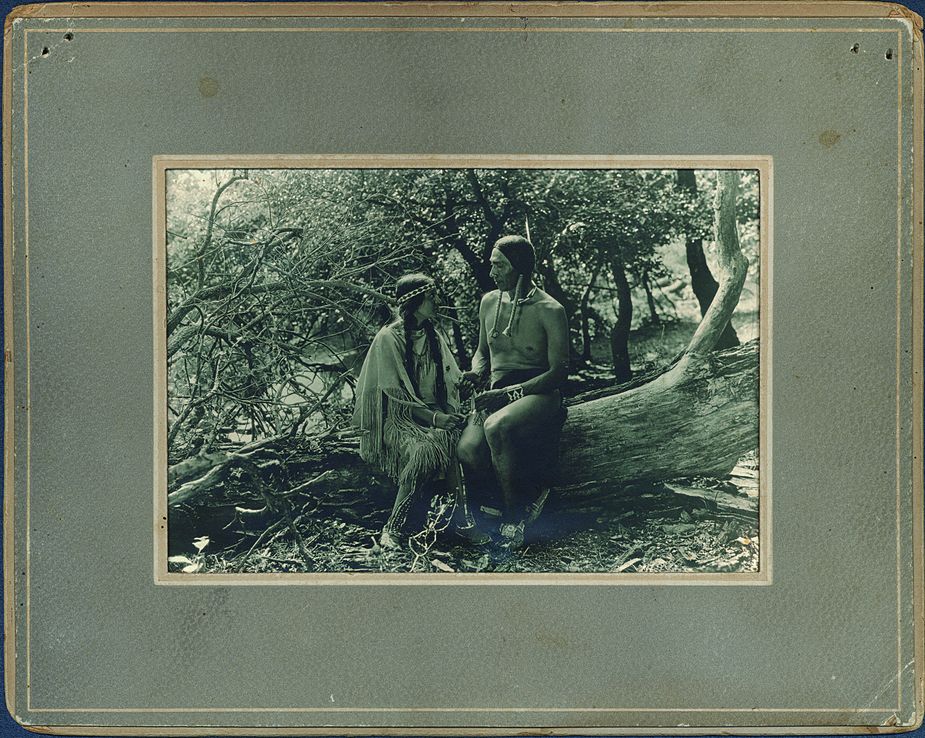

"The Daughter of Dawn" was filmed in Oklahoma in 1920. Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

A milestone of a different sort in the story of Oklahoma Westerns was the discovery and restoration of a lost silent film made in 1920 with a solely Kiowa and Comanche cast. The Daughter of Dawn was filmed in the Wichita Mountains but presumed lost until a copy turned up in North Carolina in 2004. As film curator for the Oklahoma History Center, Bill Moore worked on the film’s acquisition and restoration, a process that took seven years.

“There was so much excitement that we had a lost silent film shot in Oklahoma, and it was a story that, unlike most at the time, did not make light of the Indians,” Moore says. “This one was real life, they wore their own clothing, brought their tipis. It was an amazing film.”

The Daughter of Dawn was inducted into the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 2013 for its significant depiction of life on the Southern Plains, including a bison hunt, fight scenes, and ceremonial dance. Two of Comanche leader Quanah Parker’s children play lead roles.

For years, I have hiked the Wichita Mountains, where The Daughter of Dawn was shot, but I was eager to see them in a new light after watching the film. Surely, the ancient peaks worn to piles of pink granite boulders and their creeks, canyons, and crevices have changed little over a hundred years, and it doesn’t take much imagination to connect this landscape with the scenery in The Daughter of Dawn and the 1908 films shot by pioneer cameraman and 101 movie department head Bennie Kent.

Acting on a tip from Moore, I also took a side trip to the Lincoln County Museum of Pioneer History in Chandler. At this just-off-Route-66 museum, tucked upstairs in a small room of its own, is Kent’s well-used movie camera, along with an old projector and a suit of his clothes. Two blocks west of the museum are the historic homes of both Kent and Marshal Bill Tilghman.

In the 1920s, the popularity of Westerns led to the demise of Wild West shows. And when the first talking movie debuted in 1927, it was the beginning of the end for many silent movie stars, although a few, like Will Rogers, made a successful transition into talkies. Financial woes at the 101 Ranch—along with the far-reaching consequences of the Great Depression of the 1930s—led to its failure and dismantling. But what it had set in motion in the entertainment world lived on.

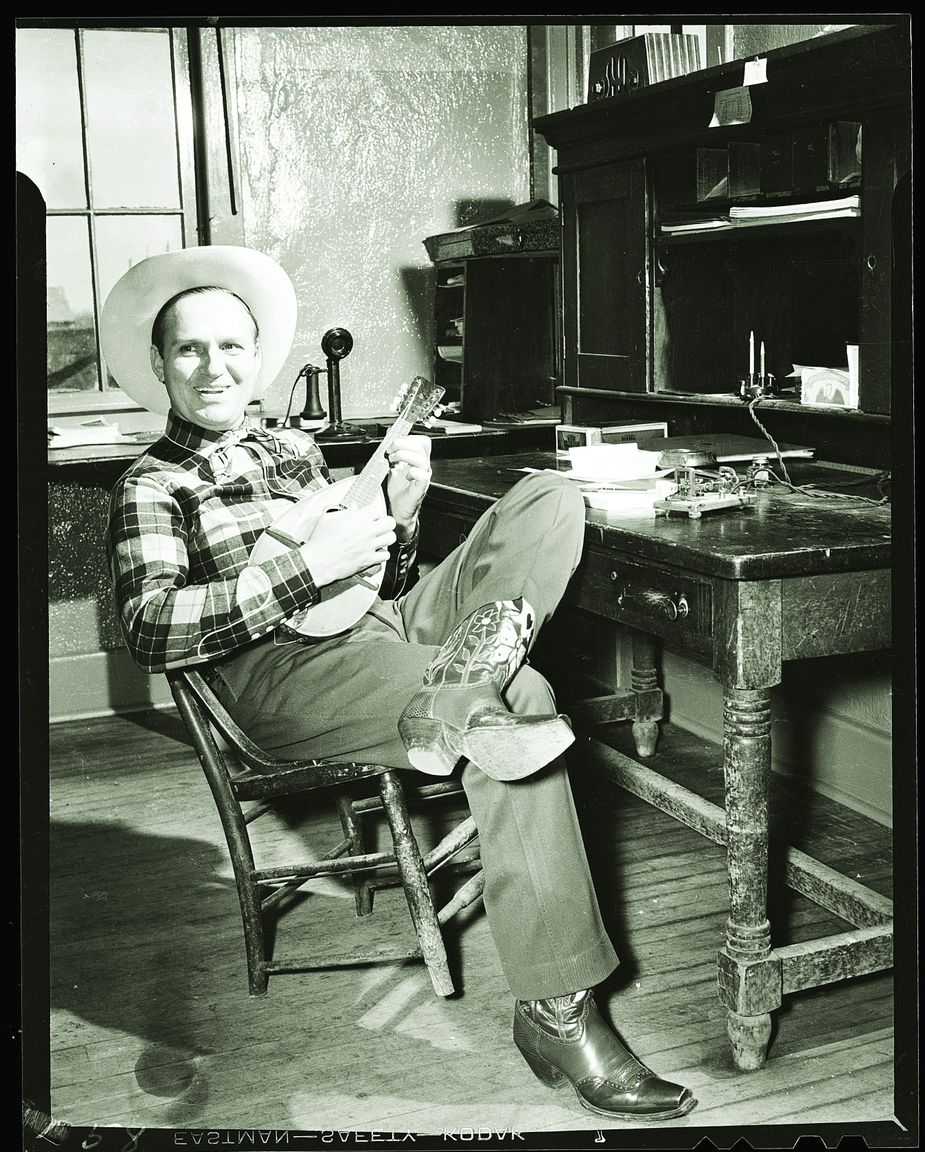

In fact, the talkie era introduced many new talents to the genre. In the 1920s, Gene Autry was filling in for a telegrapher in Chelsea, singing and playing his guitar to bide the time when, legend has it, Will Rogers walked in. That discovery led to Autry’s career as a singing cowboy, and he eventually starred in ninety-three movies, earning a billing as “America’s Favorite Singing Cowboy.” In 1941, the southern Oklahoma town of Berwyn changed its name to Gene Autry and today boasts a museum full of movie posters and memorabilia in tribute to Autry and other singing cowboys. That includes Roy Rogers, whose wedding to Dale Evans took place just north of town, near Davis. In fact, the application for the couple’s marriage license is on display at the Arbuckle Historical Society Museum in Sulphur.

Then there’s actor and rodeo champion Ben Johnson, whose father worked at the 101 Ranch before becoming foreman of the Chapman-Barnard Ranch. Johnson went to Hollywood in 1939 as a wrangler along with a delivery of horses purchased by Howard Hughes, which led to work as a stuntman in Western films, including a job doubling for Henry Fonda. Later speaking roles made Johnson a major star. He received a Best Supporting Actor Oscar for the 1971 film The Last Picture Show. In June 2019, a museum celebrating Johnson’s legacy opened in Pawhuska.

Oklahomans like James Garner, Dale Robertson, and Wes Studi also have left their marks on Westerns. The city of Norman pays tribute to native son Garner with a large bronze statue on Main Street.

The south-central Oklahoma town of Berwyn changed its name to Gene Autry in honor of the star on November 16, 1941. Tens of thousands attended, and the celebration was broadcast live on the "Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch" variety show. Photo courtesy of the Oklahoma Historical Society.

And no tour of Westerns in Oklahoma would be complete without a visit to the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. The Western Performers Gallery honors icons of Western culture, including many with 101 Ranch origins, and a multimedia review with clips of many early Western films.

But Western filmmaking in Oklahoma is not a thing of the past thanks to two Enid brothers. Rick and Larry Simpson’s Skeleton Creek Productions has produced six family-friendly Westerns using locations like the Gloss Mountains and Woolaroc, as well as their museum in downtown Enid. Their most recent release, Canyon Trail, garnered a crowd of more than 1,100 at its 2015 Enid premiere. Not surprisingly, they have 101 Ranch connections: The Simpsons got into the movie business through Ben Johnson, a lifelong family friend. Their grandfather also had a grocery store in Dewey and traded with Tom Mix.

For more than a century, Westerns have captivated audiences around the world. Oklahoma, and in particular the 101 Ranch, played a singular role in the genre’s development, leaving a legacy that Oklahomans can experience and appreciate. While the physical remains of the 101’s vast empire are scattered, its glory lives on through artists of the genre from John Ford to the Coen Brothers—who wrote, directed, and produced the 2018 Netflix western The Ballad of Buster Scruggs starring Tulsa native Tim Blake Nelson. Anyone who has ever enjoyed a tale of the Wild West and smiled as the heroes rode off into the sunset owes the 101, and Oklahoma, a debt.

.png)