Jefferson Revival

Published May 2023

By Robert Reid | 18 min read

Mayor Coy Holt looks up from his phone.

He’s at the head of a table in the civic hall in the Pittsburg County town of Savanna, population 618. Surrounding him under a fluorescent glow are a baker’s dozen of organizers and tourism folks from across southeastern Oklahoma. They’ve come on a Friday afternoon to hear how their towns can be transformed into Route 66-style attractions.

“What’s the selling point for a town like Savanna?” Holt asks. “We don’t have no historic buildings.”

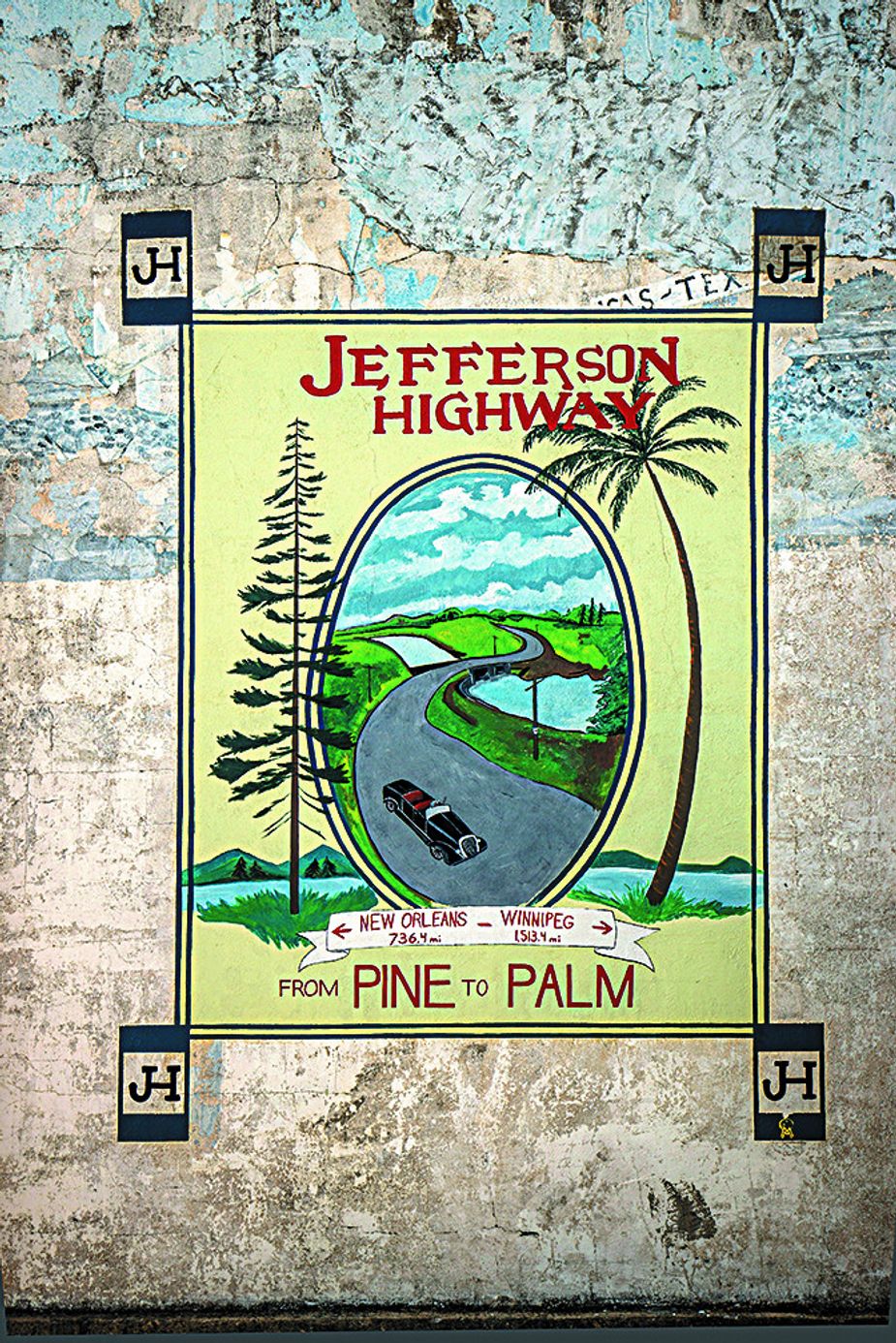

This mural in Caddo pays homage to the historic Jefferson Highway. Photo by Shane Bevel

All eyes pan across the room to Roger Bell, the bearded Muskogean who’s just given an hour-long PowerPoint presentation about the pretty obscure highway that first passed out front a century ago.

“You have more things than you realize,” Bell answers.

And it’s here my adventure along the Jefferson Highway, a road that predates Route 66, begins.

This 2,300-mile highway connecting New Orleans with Winnipeg, of all places, was named for Thomas Jefferson, as it cut across what had been his Louisiana Purchase. It materialized in the 1910s and 1920s after Edwin Thomas Meredith, the Iowan founder of the Meredith Corporation, figured the country ought to do “big things other than war.” Local support was immediate for what often was called the Palm to Pine Highway, which eventually ran through eight states and a Canadian province, including 275 miles of Oklahoma. Back then, there were more Model Ts than places to drive them.

A scenic stretch of Jefferson Highway between Oktaha and Summit. Photo by Shane Bevel

But what became known in shorthand as The Jefferson—one of the hundreds of highways built during that era’s paving fever—never had a heyday like Route 66 did. In the 1920s, back when motorists needed three weeks to complete a one-way trip, the federal government replaced all highway names with numbers. Thirteen in all took the Jefferson’s place, and its former name fell into oblivion. These days, few people you meet on the road have any idea they’re on a historic highway to Manitoba’s capital city.

My three-day journey on Oklahoma’s original route takes some planning on jeffersonhighway.org, marking up my Oklahoma road atlas and, once on the road, some imagination. I’m not expecting to find untouched 1920s life in towns like Vinita, Muskogee, or Durant. Instead, I’m following its course to explore modern-day Main Streets—and to ponder the same histories that would have lurked out the window back in 1923.

Entering the abandoned town of Picher from Kansas via U.S. Highway 69, I ride toward Miami’s downtown, where the road briefly joins Route 66. I breeze by alley murals and the art deco Coleman Theatre, but the Jefferson’s dance with the Mother Road is brief. South of Miami, it veers west via U.S. Highway 59 to the tiny town of Welch.

Yoder's Dairy near Chouteau. Photo by Shane Bevel

The Jefferson Highway creation story was grassroots, unlike the corporation-funded Lincoln Highway connecting New York and San Francisco. Building the Jefferson took ample pluck from a string of organizers who rallied support and raised funds through subscription donations. Today, this pep is personified in Winston McKeon, Welch’s mayor.

I ride past a diner and guitar shop on the wee main street to the town hall. Inside, McKeon’s Welch Wildcats shirt is tucked into faded jeans, his gray hair pulled into a ponytail.

“When I returned here in 2001 to teach music at the high school, everything was tired, propped up, dusty,” he explains.

The Jefferson’s revival is the town’s opportunity, he believes. After retirement, he’s planning to turn Welch’s old Sinclair gas station into an info stop with ice cream.

“My glass is always half full and overflowing,” he says. “The promise of the future has hope embedded.”

A wayfinding sign along the Jefferson Highway in Muskogee Photo by Shane Bevel

The novelty of a north-south highway in a continent known for westward trails wasn’t lost on its founders. And yet the Jefferson has more precedence than later roads like Route 66. As Muskogee historian Jonita Mullins writes in her 2016 book Jefferson Highway in Oklahoma, its bedrock was “the work of the great bison.” The Osage turned animal trails into the Osage Trace in the 1700s. It later became the Texas Road, which eventually was paralleled by the Katy Railroad.

The land itself, it seems, wants us to go this way.

I think of this south of Chouteau. I take a gravel road to an Amish farm called Yoder’s Dairy. I decide against a gallon of raw milk, instead leaving a few dollars in the money jar for some strawberry jam. Next, I head off U.S. 69 to Wagoner. After a pulled-pork sandwich at Smokin’ Sisters BBQ downtown, I pop into the Wagoner City Historical Museum and enjoy a sprawling survey of Tulsa music promoter Jim Halsey.

“If we had money, we’d be dangerous,” an energetic volunteer named Del Davis tells me.

The Roxy Theater in downtown Muskogee. Photo by Shane Bevel

When I mention the Jefferson, she calls the mayor.

Within five minutes, Mayor AJ Jones, who regularly stops his day to meet Jefferson travelers, is leading me across the street to the Cobb Building, which now is a bank, to see a panoramic photo of a 1920s car club on the highway. He hopes this road fever will return, ideally with a Route 66-like passport system to lure in travelers following the highway’s blue signs.

“I only learned about it seven years ago,” Jones says. “It blew my mind. I jumped all over it.”

Today, Jefferson travelers spend a fair share of time on the four-lane U.S. Highway 69. But the true route regularly breaks off it. They are detours worth taking. One, via two-lane State Highway 16 south of Wagoner, bends its way into the town of Okay. Here, I find Roger Bell in a blue Jefferson Highway shirt standing next to his Chevy Colorado which is, yep, Jefferson Highway blue. As president of the national Jefferson Highway Association, he aims to get anyone and everyone from Manitoba to Louisiana to embrace the highway’s potential. He sets up annual conventions and regularly talks with communities, as I saw in Savanna. Increasingly, more road trippers in old Chevys are trickling along the route.

Fried pies in Stringtown. Photo by Shane Bevel

Bell takes me to a recently collapsed 1922 bridge over the Verdigris River near the Three Forks area, where early explorers and Cherokees and Mvskokes on the Trail of the Tears came through. I follow him from here into Muskogee, losing count of the Jefferson Highway signs we pass on the way. We peek at an original Jefferson tourist camp at Spaulding Park then ride through downtown to the Three Rivers Museum, formerly the Midland Valley Railroad Depot.

Inside, Bell leads me to his baby in back: the biggest exhibit on the Jefferson Highway anywhere. A video loops next to an assembly of old license plates from Manitoba to Louisiana and 1920s packing items like a portable picnic kit.

“I’ve got the bug now,” he says of his efforts. “It’s addictive once you get it.”

The next morning, the route leads me onto Oktaha Road south of Summit. A century ago, road trippers wouldn’t have known they were passing the site of the decisive Civil War battle at Honey Springs. Here, on July 17, 1863, shortly after Gettysburg, Union troops wrested control of the key Texas Road from the Confederacy for good. I watch a three-screen video at the new visitors center, which opened in 2022, and walk on Trail 3 to a clearing of the old Texas Road in the woods.

As I return to U.S. Highway 69 at Checotah, the road rises to a panorama of distant green hills then descends toward the muddy banks of Lake Eufaula. I stop for a coffee in Eufaula’s lovely downtown then continue on. At one of the antique shops in north McAlester, I mention the historic highway to the dealer, who replies, “The what?”

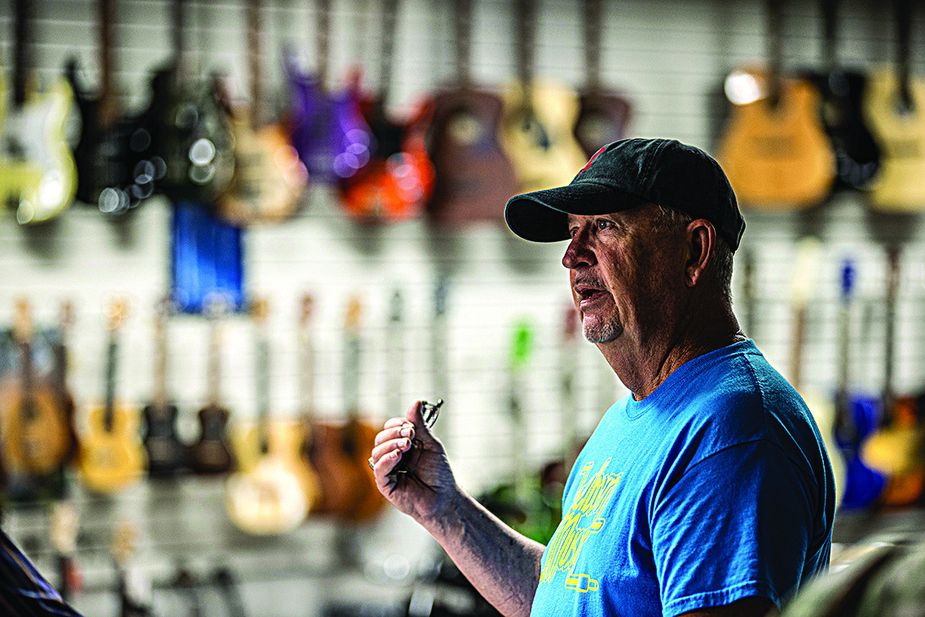

David Welborn owns Welborn Music in Durant. Photo by Shane Bevel

This lack of awareness is common. But not in my next stop, Stringtown.

South of Kiowa, this town of 454 feels like a lost corner of Appalachia. Hills tightly frame the town once known for its rock-crushing plant. Today, it’s the twenty-first-century poster child for the Jefferson Highway due to its community efforts like fried-pie fundraisers, a Jefferson Highway 5K run, and posting—at my count—twenty-six Jefferson Highway signs.

A Stringtown organizer I meet in Savanna, Becky Richards, gives me Dance of Death, a short book by a local ninety-something writer Wilma Fugate Magby. It tells how Clyde Barrow—before he knew Bonnie—killed a deputy at a 1932 town dance while trying to kidnap a local girl he’d fallen for.

I want to find the girl’s home site on the Jefferson, which I am told is past the iron truss bridge over the North Boggy Creek. I bounce along one of Oklahoma’s eleven “adventure roads”—Bell’s term for unpaved stretches of the original. Two miles south, I find the bridge has become a spray-painted testament to local couples’ enduring love. The house is long gone, but I stay a minute to imagine the girl, Sadie, running across the Bermuda grass with a pail to fetch some water.

Now, I’m itching for more adventure roads. Oklahoma’s longest runs two dozen miles south of Tushka. I ride it in pure seclusion, barely seeing the sky through the cavern of trees above me.

Miami’s downtown is an outdoor art gallery of murals. Photo by Shane Bevel

It leads to Caddo. I park on a cute block of century-old brick buildings on Buffalo Street, looking a lot like they did in a photograph Dorothea Lange took here in 1938 on her famed trip documenting Depression-era hardship. A quick walk reveals a lot happening: a tiny vintage clothing shop, a one-screen cinema offering popcorn gift certificates, and the gorgeously restored Harbinger Beer Company with five-dollar pints and weekly concerts.

I step into the Indian Territory Museum across the street and find a hoot of yesteryear memorabilia. I take a selfie in the town’s old jail cell, browse through photo albums of Caddo’s 1918 Corn Carnival, and sit a spell with the spry post-retiree volunteer running it. Around here, Joyce Alexander is apparently known as the woman who knows everything about everything.

“Well, I’m not that good,” she laughs. “But I read. I ask questions. I try to get it right.”

Honey Springs Battlefield in Chectoah features a new visitors center that opened in 2022. Photo by Shane Bevel

My last main stop on the road is Durant (pronounced “DOO-rant”). It feels big; it takes a minute to find parking downtown. I walk through an alley of colorful murals then stop at Welborn Music, which opened under a different name before World War I. Inside, something glimmering on the wall quickly captures my attention: a gold record for Buddy Holly’s 1957 hit “That’ll Be the Day.” I ask about it.

“My brother was sort of a Cricket,” owner David Welborn explains, referring to Buddy’s backup band in Lubbock, Texas.

Larry Welborn, who passed away last year, played stand-up bass on a couple songs on Buddy’s “Chirping” Crickets album, including that number-one song. Royalties still come in.

Cody Parris co-owns the popular Muskogee Brewing Company. Photo by Shane Bevel

Afterwards, I take the window seat at Opera House Coffee, a huge café built in downtown’s old theater. Sipping a café Americano, I’m thinking there really is something to this old bison trail that prompts more finds and histories than expected.

My ride ends sixteen miles south as the Jefferson crosses the Red River into Texas. But before returning home, I still have one thing left to do.

I get back on U.S. Highway 69 and drive back to Savanna, that town with supposedly no historic buildings, right to the town hall. There, I follow a narrow, bleached strip of concrete neatly cracked in the middle. This surviving patch of the Jefferson leads me into the woods north of town. I stop at a century-old truss bridge and get out. The faint hum of eighteen wheelers on 69, a couple hundred yards east, hovers in the air. But this old road, I have to myself. I kneel to look. Crude, unique, bite-sized chunks of crushed aggregate smile back like floating fossils captured in a bygone road-tripping era.

No patch of the Jefferson I’ve found feels quite as lost in its origins. No place feels more 1923. And finding that is worth the trip.

For more information on the Jefferson Highway’s route through the Sooner State visit jeffersonhighwayinoklahoma.com.

To learn more about the Jefferson Highway Association visit jeffersonhighway.org